Peter Schuttler History - Part 2 of 3

"Finding The Way"

Long before Henry Ford, Louis Chevrolet, and the Dodge brothers began making their own tracks with travel in America, there were numerous wood-wheeled moguls unknowingly laying a solid foundation for the upcoming auto industry. Existing for hundreds of years, a massive network of horse-drawn vehicle makers and mechanics grew to include tens of thousands of shops and factories across the U.S. For the largest makers, their business-minded toolchests included the establishment of vast distribution networks with sophisticated advertising and promotion campaigns, company reps, event marketing, jingles, slogans, and even professional ambassadors - all of it taking place well before the twentieth century automobile.

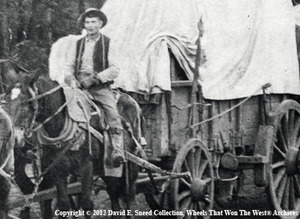

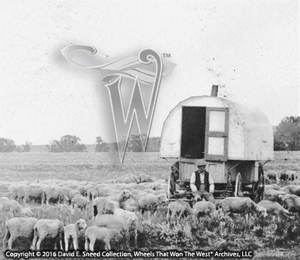

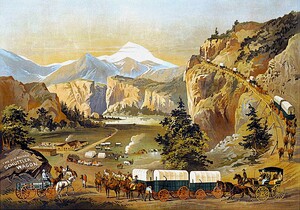

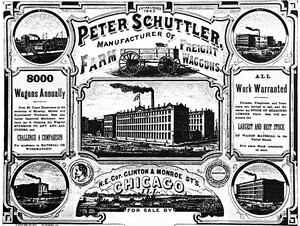

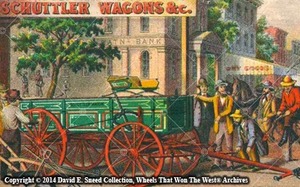

As we began sharing last week, the Peter Schuttler Company from Chicago was one of the most successful and highly regarded manufacturers of wagons, carriages, buggies, and sleighs. They were especially focused on crafting wood-wheeled products to take on the toughest challenges. From enormous, tall-sided freighters carrying essential goods to and from the American West to iron clad ore wagons, emigrant wagons, city drays, business vehicles, sheep camps, and legendary chuck wagons on famed cattle trails, the Schuttler name enjoyed a powerful reputation on the American frontier. While the brand ceased being made in Chicago in 1925, the label still enjoys one of the richest and most interesting histories of any early western vehicle company. Overbuilt and artistically designed, Peter Schuttler wagons have long been hailed for their significant ties to the Old West.

Peter Schuttler wagons were well known on the frontier and on period cattle drives. Image Copyright © David E. Sneed, All Rights Reserved.

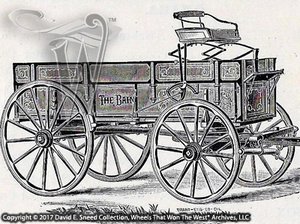

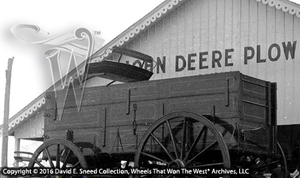

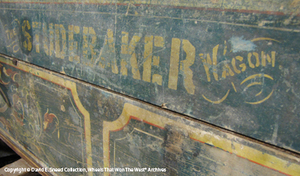

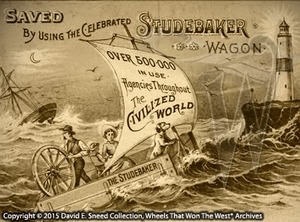

So distinct is the legacy of the firm and the vehicle construction itself, that outside of legendary stagecoach builder, Abbot-Downing, many consider the company to be one of the greatest brands of early western vehicles. Of course, there are a few other national brands that could also vie for a role in that title. Among them are labels like Bain, Cooper, Espenschied, Fish Bros., Jackson, Kansas, Mitchell, Moline, Murphy, Newton, Stoughton, Studebaker, T. G. Mandt, Weber, Winona, and more.

With today's benefit of hindsight, it's easy to see how Peter Schuttler's work and reputation set a very high bar for competitors. As he struggled to find his niche, his continual move westward gave him a leg up on many competitors while also putting him in great position to capitalize on America's movement west. Even so, as my granddad might have said, "it had been a hard-row-to-hoe" since the day Schuttler left Germany for America. He had survived a treacherous two-month ocean voyage, near starvation from lack of food and work, building vehicles that no one wanted to buy, and a six-month battle with typhoid fever that nearly killed him. Through it all, his determination to succeed continued to drive him west.

His ultimate hope was to find a town where he could sell his vehicles to the community as well as to those traveling farther west. So it was that in 1843, nine years after first touching American soil in the port of New York, he rented a small, wooden shanty on Randolph and Franklin Streets in the six-year-old city of Chicago. One benefit of the meager place was that he didn't have go far to get to work. He and his family lived in the back portion of the drafty clapboard shop. With a population of around 3,800 people, the area was certainly large enough to support him, but there was another problem - there were already thirteen other wagon makers in the city. Competition was intense, but that seemed to be a position Schuttler was increasingly comfortable in. He went to work - hoping his work ethic, persistence, and overbearing commitment to quality would pay off this time. In the beginning, Schuttler was working two jobs: that of a wagon maker and, believe it or not, a Brewmeister. While he and his father-in-law built the brewery, the first batch was an abject failure and a discouraged Schuttler wanted no more of the fermentation business. Instead, he determined to stick to what he knew, which was wagon-making. (As we'll see later, this is not the last time that the Schuttler family is connected to beer-making)

Peter Schuttler's original wagon shop as it first appeared in Chicago in 1843.

A period 'horse power' running a saw.

Like many new businesses, Schuttler's wagon shop had a slow beginning. Doing all the work by hand, he eventually invented a lathe and other machinery propelled by a horse power. (A horse power is an elevated treadmill with a wooden conveyor track connected to gearing that's linked to other automated machinery such as saws, drills, lathes, sanders, and the like. Depending on the equipment being powered, it was common for a dog, sheep, goat, or horse to be placed on the treadmill to help provide the energy needed - see image above). Gradually, Schuttler was able to acquire an eight-horsepower engine to run the shop machinery. He also began to hire a few helpers and expand his business to a four-story brick shop measuring forty feet by seventy feet. Not only was he manufacturing buggies, carriages, and wagons but he was also making and selling harness from the repository he had set up in the same building. It was about as close to a one-stop transportation shop as a customer could get. With so much happening, Schuttler was putting in eighteen-hour days, finally getting a solid foundation and direction. Then, once again, disaster came calling.

Fire - the frequent visitor and sworn enemy of all horse-drawn vehicle makers, burned virtually his entire business in 1850. Filled with flammable contents like paint, solvents, seasoned wood, coal, and hot forges, fire in early vehicle factories was a common occurrence. Adding insult to injury, Schuttler's insurance company refused to cover the losses. It was a crossroads for the emigrant... a time for reflection and decisions that would affect the Schuttler family for generations to come. He was all but ruined and, from that time forward, had such a disdain for the insurance industry that the senior Schuttler never again took out another policy. Tired, frustrated, and full of questions, he made one more choice to embrace adversity. Taking the fire as a sign of opportunity - he rebuilt. And this time, he grew even stronger. The tragedy had become a turning point, forging his resolve and forever marking him as a leader among the most revered early heavy vehicle makers. From this time forward, his business prospered. After a decade of struggle, sales in 1853 amounted to an incredible $30,000. That's the equivalent of well over a million dollars today and, in subsequent years, the income multiplied many times over.

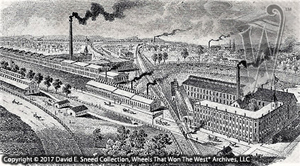

This 1869 map shows the layout of the Peter Schuttler factory at that time. Note the corner of Randolph and Franklin Streets.

At work before daylight and still toiling until well after dark, it wasn't just Schuttler's office hours that stood out, his vehicles also turned heads. Distinctive and elaborate striping, fancy flourishes, and artfully curled brush strokes became a signature of sorts with genuine visual appeal. Wood edges were chamfered, contoured for style, functionality, and durability. Even the metalwork took on a different look, being tailored as if to say, "I'm unlike others for a reason." It was a discreet yet tasteful panache that further set the designs apart.

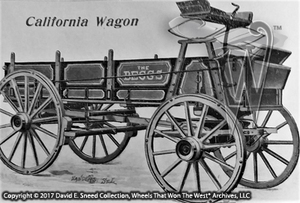

During the Mormon exodus to Utah, Brigham Young is reported to have highly favored Schuttler's designs over other makers. So much so that by 1855, the Mormons are said to have been using his vehicles extensively. Combined with sales to several St. Louis freighting firms and a continual stream of emigrants moving west, Schuttler's fame was spreading fast. In the mid-1800s, Schuttler had a production rate of 135 wagons completed each week. They were known as Chicago Wagons and quickly found homes throughout the U.S. and its territories as well as Mexico, British Columbia, and beyond. Without question, Schuttler's new-found fortune came more from determination than luck. His vehicle designs weren't merely functional, they were rolling works of art and built to take a beating. A modern-day parallel might be found in high-end SUVs. With the extra attention he gave to style lines, ground clearance, strength, durability, and innovative genius, he set a standard that is still revered by collectors today.

This segment from a dealer billhead shows the 'Chicago' wagon term that Schuttler wagons were known for. Image courtesy Wheels That Won The West® Archives. All Rights Reserved.

Schuttler was equally savvy on the promotions front. Like the modern automotive industry, wagon makers in the 1800s often attached their own hyperbole to advertising rhetoric. Schuttler's go-to tagline was "The Old Reliable." It was a slogan that was easy to remember and often copied. Perhaps most important, though, it seems the short motto truly reflected the owner experience. Further reinforcing the bellwether nature of the brand, in a bio of the company published in 1918, Schuttler is given credit for his designs literally changing the accepted look and configuration of wagons in the 1850s; effectively putting the curved beds of old-fashioned prairie schooners permanently out to pasture.

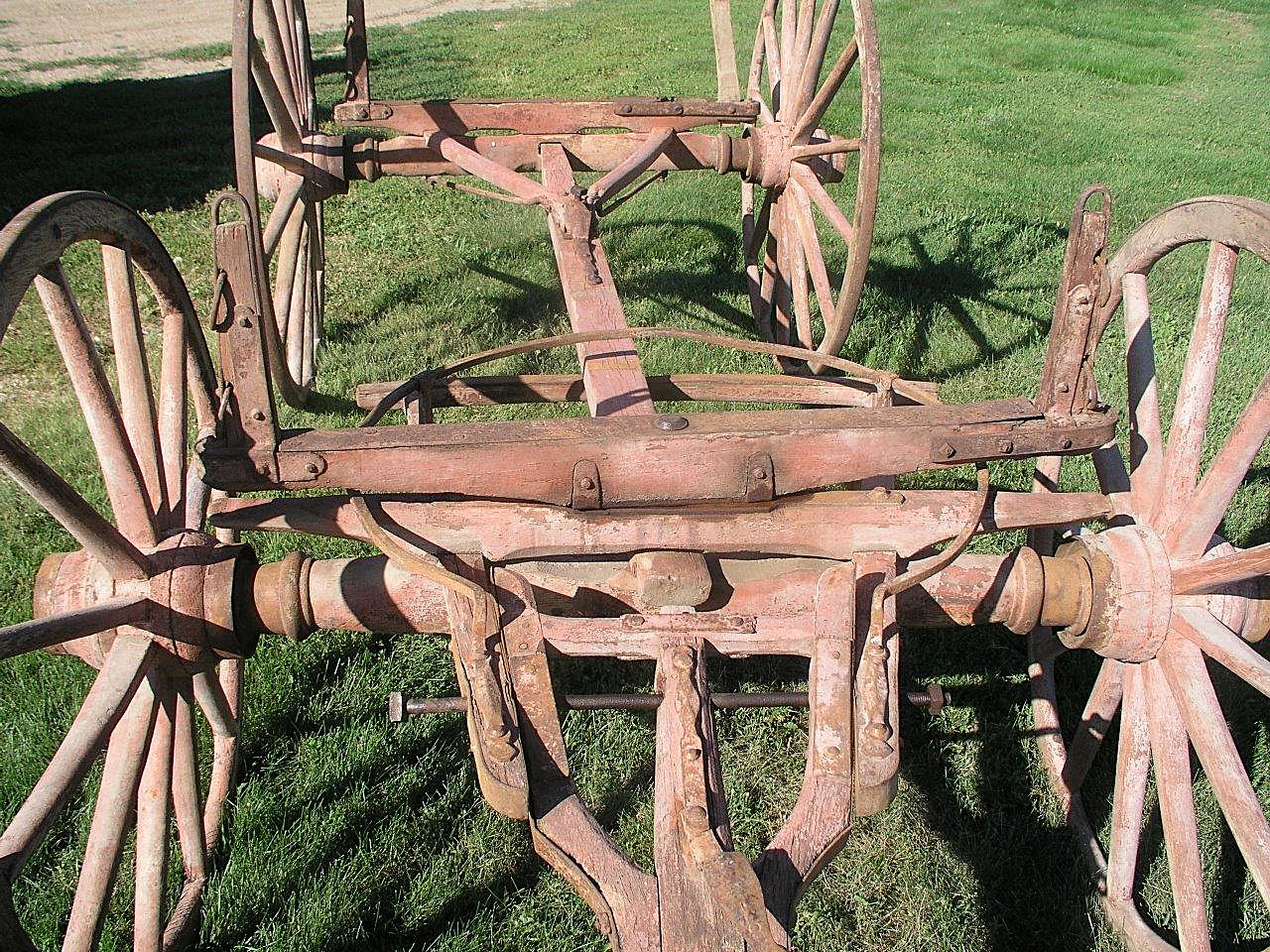

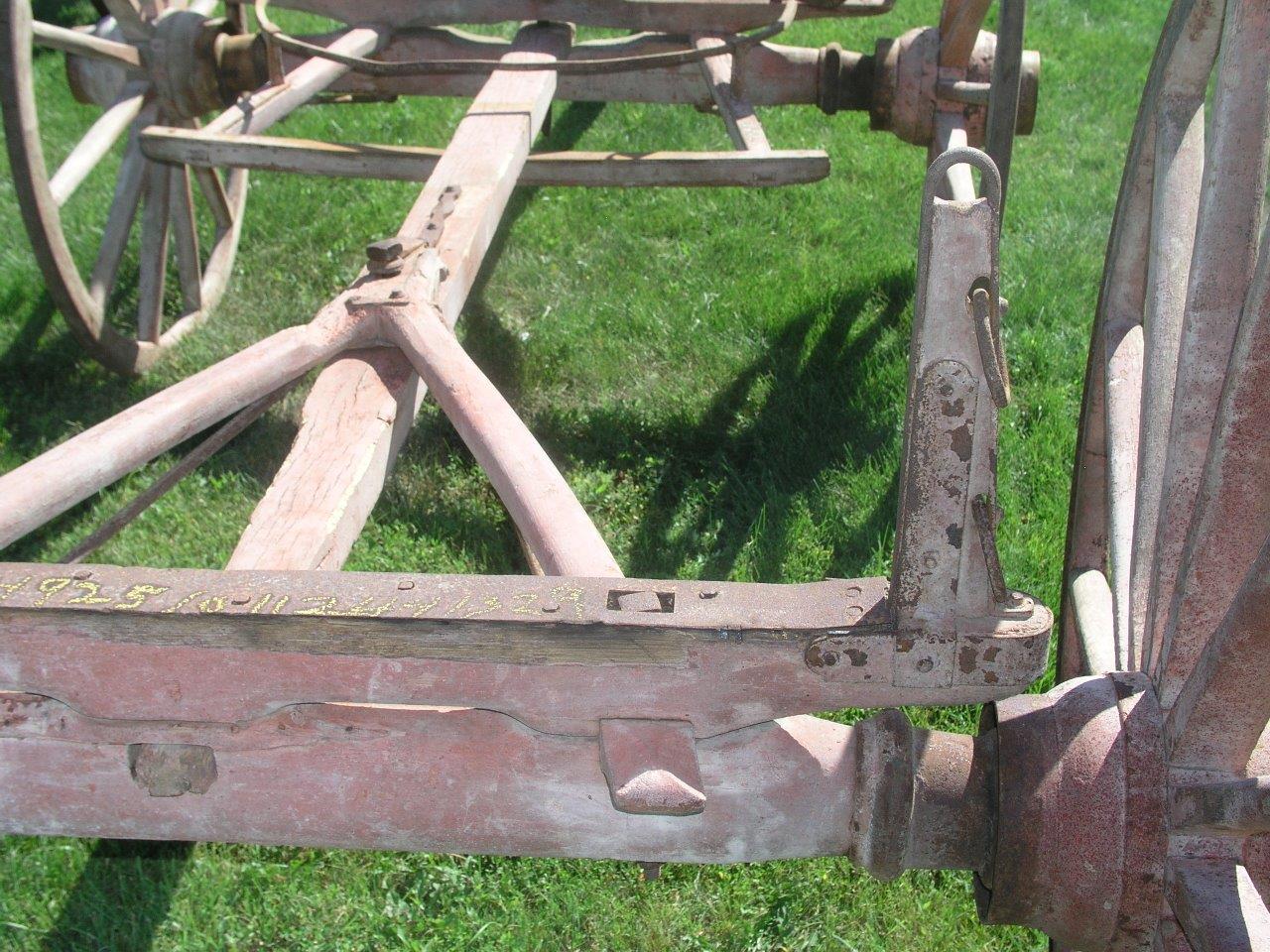

Other period accounts share that Peter Sr. worked right alongside his other employees through the year 1856. Ironically, there's another transportation event that was destined to intertwine with Schuttler that same year. In September of 1856, a steamboat by the name of Arabia was headed west on the Missouri river. It was loaded with a whopping two hundred tons of goods destined for the frontier. If it could be imagined in that day, it was on that boat... food, clothing, footwear, tools, building materials, a printing press, guns, knives, fabric, buttons, exquisite Chinaware, flawless crystal, colored glassware, eating utensils, a pre-fabricated house, and much more! Yet, none of it would reach its destination. Tragedy was waiting just west of Kansas City when the steamer ran headlong into a giant walnut snag and sank. Everyone but an unfortunate mule was able to escape. Almost all the goods on board were lost to the river... That is, until 1988, when the Hawley's, a local family of history hunters and HVAC experts, successfully located and dug up the boat. In the 130-plus years since it had sunk, the river had shifted and the boat was found a half mile inland of the present channel and forty-five feet below the surface of a Kansas cornfield. The treasure trove of goods onboard is now known as the largest collection of pre-Civil War artifacts in the world. Among the thousands upon thousands of items is a Peter Schuttler running gear that we were the first to identify during a visit on March 28, 2007. There is sufficient evidence to suspect that the gear in the museum was crafted by Schuttler himself. It was most certainly inspected, approved, and sold by him. Because the gear never had the chance to be used, the measured scribe marks and scalloped contours are still as fresh as the day they were cut.

The Steamboat Arabia was carrying 200 tons of cargo when it sank in 1856. Image courtesy of the Steamboat Arabia Museum.

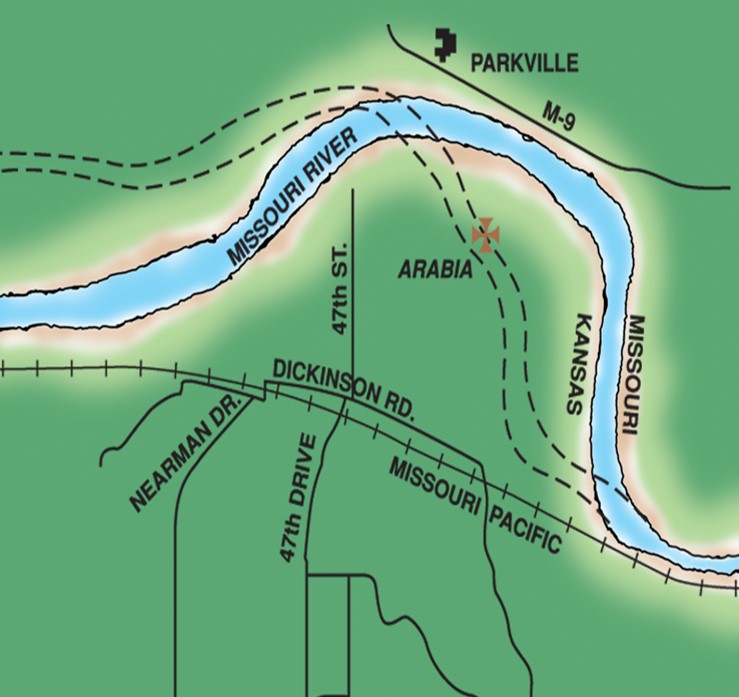

The above map shows the location where the Steamboat Arabia was found as well as the shift of the Missouri River between 1856 and 1988. Image courtesy of Steamboat Arabia Museum.

This Missouri mule was the only life lost when the Steamboat Arabia sank in 1856. Image courtesy of Steamboat Arabia Museum.

This photo shows the 1856 Schuttler gear from the Steamboat Arabia. After identifying the maker of this running gear, I was given exclusive access to document and photograph the wagon. Image Copyright © David E. Sneed, All Rights Reserved.

The story of the excavation is an amazing account in and of itself. I've written about it several times and, later this year, plan to repost the details from an article I wrote for the January 2008 issue of The Carriage Journal. The Steamboat Arabia Museum in Kansas City is an unforgettable place to visit and the Schuttler running gear there is likely the oldest survivor of the brand. For additional insight into this discovery, you can visit the museum's website at www.1856.com. Better yet, plan a visit. It's a journey that brings America's rich western history to life!

This extremely rare Peter Schuttler running gear will likely date to the 1860s. It's owned by Doug Hansen in Letcher, SD. Subtle differences between this and the 1856 Arabia gear show a gradual evolution of the Schuttler product. Image courtesy of Hansen Wheel & Wagon Shop.

By 1860, Peter Schuttler II had returned to the U.S. from a four-year study of civil and mechanical engineering in Karlsruhe, Germany. Upon his return, he began additional studies as well as working with his father, Peter Schuttler I in the wagon factory. He was nineteen years old at the time. His training and tutelage under his dad would be a crucial to the continuance of the company. Ultimately, neither Schuttler was a man to wait on fate. Both met life head on, creating opportunity with all the confidence of a monumental western legend.

There's much more to come! Next week we'll cover Part 3 of 3 in the history of the Peter Schuttler Wagon Company. From power, money, and connections to ghosts, gold, and gumption, the Schuttler story holds a world of intrigue.

Ps. 20:7