I’ve been closely studying America’searly western wheels for decades. Yet,the last half of that time has been the most visibly productive. I’ve learned more, found more, and sharedmore during those years. For me, thesingle-most important factor helping my growth has been the act ofcommunicating my findings to others. Why? Well, if you want todiscover how much you really know about a topic, start writing about it. It’s a process that, ultimately, requiresintensive and continual research. For historians,the need for homework remains a vital part of any serious study.

When we commit to fully explore a topic,the experience has a way of stretching and growing us. It certainly has me. Far from knowing all there is to know aboutwagons and western vehicles, the last few decades have shown me how much thereis to learn and how little of it I’ve actually mastered. Nonetheless, the process has made it mucheasier to recognize, identify, and evaluate even the smallest details. To that point, there are countlessconstruction variations on wagons made in different parts of the nineteenth andeven twentieth centuries. Knowing whodid what, when, why, and how helps develop the true personality of a piecewhile overcoming misconceptions and putting a structure in place for accuratelyassessing America’s wood-wheeled icons.

|

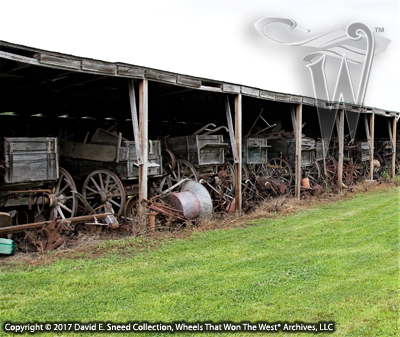

| With millions of wood-wheeled wagonscreated throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, somenear-forgotten survivors are still tucked away in secluded sheds, barns, andoutbuildings. |

Ultimately, mentally parsing every oldset of wheels has become something of a Rumpelstiltskin-style chess game forme. I love to match wits with an antiquewagon, going piece-by-piece through its makeup to see how much can beconclusively determined. Score marks,brush strokes, hammer strikes on ironwork, the custom shaping of a particularpart, patented designs, and so forth... Everything on these old wheels has something to say. Whether we understand the language or are asattentive as we should be is a different story.

Sometimes, even when a vehicle isrecognized, we may be too late to save it. More than once, I’ve borne the brunt of an opportunity missed. In fact, it’s happened to me multiple times inthe last year. In one case, I missedsaving an ultra-rare piece by just a few hours. Put into perspective, in the time it would have taken to watch themovie, Open Range, the ancientvehicle was given up, parted out, and hauled away. Dismantled, demolished, gone, and forgotten,the withered wreckage was scattered to the wind. That’s all the difference there was in thepreservation of irreplaceable history and the complete loss of an untouched artifactfrom another time. It’s a scenariothat’s hard to shake. Another onelost. Another firsthand link to the OldWest purged. Another opportunity toshare the way things were with future generations – completely eliminated. It’s a scenario that happens all too often inour search for the rarest connections to America’s western history.

Leading up to all of this, I’d been senta series of photos showing an ‘old wagon’ that the owner wanted to clean off ofthe property. As I looked at what wasleft of the hand-made hulk, I recognized the work fairly quickly. The unique design, specially-contoured wood,and hand-forged irons all contained conclusive evidence from another place andtime. The elements not only told me thebrand of the old wagon but placed its date of manufacture as early as the1870’s – maybe late 1860s! Pieces fromthese eras are extremely hard to find. Knowing the wagon was made by a St. Louis builder during or before theperiod when George Custer and the 7th Cavalry met their demise made it an evenmore unique part of the story of America. Unfortunately, by the time I was able to finally catch up with theowner, the pieces had already been disposed of. For those curious to know, the vehicle brand was a very earlyWeber-Damme. The remaining elements ofit would have made an exceptional display.

From guns and knives to clothes andtools, society has learned to recognize and respect historical treasures tiedto the life and times of America’s Wild West. Even so, there seems to be an exception for the wheels that actuallymade every part of our western growth possible. Oh, I don’t believe it’s a deliberate slight. I’m convinced it has everything to do withunderstanding what separates one make and era from another. While most folks wouldn't confuse a 1971Mach 1 Mustang with a 1991 Taurus, those same twenty years' difference in an antique wagon are often portrayed with no difference whatsoever. Clearly, there’s a difference in value as well as history between thetwo.

|

| Wagons built within the individualdecades of the 1800’s can vary greatly. Understanding when certain designelements came into use is an essential part of any authoritativeevaluation. |

So, why have we not been as successfulgetting the same message across about America’s early transportation? At the end of the day, I believe this shortfall is the real reason so many of these pieces remain unrecognized. Too often, the results lead to valuablepieces being categorized as rudimentary minutiae. From modern westerns to casual auctionlistings and even representations in museums, there has long been an epidemicof misguided mindsets on early wagons. We've drifted so far into vague, surface-level generalities that it’s a common occurrence for twentieth century farm wagons (evenfarm 'trucks') to be displayed as nineteenth century western relics. In fairness, I’m confident most don’t realizethe mistake - even though there can be numerous differences. Ultimately, though, what I’m asking is... Shouldn't we want to keep the right history with the right pieces? Don’t we owe that to future generations?

Reinforcing that point a bit more, this past year I traveled to a half dozen museums – some in the east but, most were west ofthe Mississippi. Of course, each had atleast one type of exhibit in common – antique wagons. I enjoy looking at vehicles all over thecountry as there is often a great deal to be learned. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of ‘un-learning’that needs to be done in some circumstances as well. I’m referring to a lack of objective research that sometimes accompaniesa vehicle’s supposed provenance and interpretive signage. Again and again, I’ve come across inaccuratedetails attached to a particular vehicle. In many cases, the background of the vehicle claims to be from such andsuch a date and made by so and so maker. Sometimes this information is well documented. Unfortunately, I could give countlessexamples of times when the professed ‘facts’ have not been properlyvetted. One encounter from last yearepitomizes these types of challenges...

Clearly, no one is perfect and mistakescan and will occur. Even so, oneoversight I stumbled upon was a doozy! Ivisited a large museum last summer with quite a few early vehicles. After paying to enter, one of the first piecesthe self-guided-tour brought me to was a metal-geared, covered wagon purportedto have brought a family from Ohio to the Dakotas in 1882. The details were so specific that it sounded as if there must have been some corroborating documentation. After reading the signage, I began tovisually dissect the wagon. First, I’llsay this... metal wagon gears were in existence during (and well ahead of) the1880’s. So, in and of itself, that pointis not an issue. Looking over the gear,though, it quickly became clear that this was no ordinary – or necessarilyearly – running gear. It was a highlyidentifiable Bettendorf brand, made in Bettendorf, Iowa no earlier than, andlikely well after, the mid-1890’s. IfI’d had greater access to the piece, it’s quite plausible I could haveconfirmed that the undercarriage would date to several years after the turn ofthe century.

Okay, that was the running gear. Looking at the box, it was devoid of originalpaint or obvious markings. However, as Iscanned the piece top to bottom and side to side, it too was full ofrecognizable design elements. Withoutexception, it was an exact duplicate of Studebaker’s “Twentieth Century” wagonbox. These boxes (beds) were promoted asthe industry’s most advanced designs and were featured in Studebaker promotionsfor over a decade. Reinforcing theprominent marketing of this design, the box possessed exclusive and patentedfeatures dating no earlier than the immediate timeframes surrounding the turnof the twentieth century. I get noenjoyment from debunking purported history and, in reality, the truth is oftenmuch more interesting than hearsay generalizations passed on as fact. From the beginning, my own focus has been tohelp others with supportable documentation and appropriate details related to aparticular set of wheels.

Beyond the obvious thought that erroneousinformation should be corrected, why should these slip-ups be a concern to anyof us? Well, if we don’t share accurateinformation, society tends to make up its own stories, effectively lumpingevery one of these vehicles into a single, catch-all class of sameness. It’s a process that has historicallypositioned these vehicles as a relatively irrelevant part of our past. The end result is that we miss out on the evolution of transportation design and how/when it was being used duringsome of the most stirring days and events of the Old West.

|

| Like many other brands, ‘Weber’ wagons were craftedin a number of design and paint configurations over the years. |

Over and over, we all see antique wagonsviewed as overly-simplistic, ubiquitous creations with little more to offer thana quick photo op in a simple yard display. It’s exactly how the casual perception of these pieces can lead to thembeing burned up, melted down, parted out, or buried in a forgotten holesomewhere. When true identities and authoritative provenance are lost, devaluationcan quickly follow. Over the years,I’ve restrained many of my thoughts on this subject out of respect for those placingthese pieces on display. More and more,though, I’ve come to believe this restraint has actually helped in the loss ofkey parts of American history.

Some of the most popular searches forwagon history on the internet involve folks looking for details on MurphyWagons. Have you ever wondered why thereare no confirmed, period examples of brands like Murphy, Espenshied, Jackson(I’ve actually seen one), or other legendary brands that played such a strongrole in building the West? Is it becausethey’re already gone? I don’t believethat’s totally true. Yes, attrition hastaken a hard toll on these wooden warriors. Even so, the most important point, I believe,is that we often don’t recognize the identity of an old piece when we seeit. All wagons look the same, or so societytends to think. So, time and again, welook at an old piece and allow ourselves to be satisfied with not satisfyingany element of curiosity. In some cases,the lack of action (or a delay) is a death knell for a rare and legendary piece.

This September, the Santa Fe TrailAssociation will hold a symposium in Olathe, Kansas. There will be a host of topics covered. As part of the event, I’m privileged to sharesome details on early wagons and their development. The hour-long presentation will include points not typically available – even in my blogs or articles. If you have an opportunity to attend, I’denjoy seeing you there as well as the chance to hear about your finds andchallenges. In the meantime, if youhappen across an old wagon with features you don’t recognize or maybe seem tobe a little different – shoot me an email with some clear photos. At the end of the day, it takes all of us topreserve history. YOU could make all thedifference in helping showcase an ultra-rare part of our past or losing itforever.

|

| When closely evaluated, it’s fairly easyto point out differences between wagons produced in different time periods ofthe nineteenth century. |

Thanks for stopping by today. By the way, if you haven’t signed up to receive this weekly blog via e-mail, just type your address in the "Follow By E-mail" section above. You'll receive a confirmation e-mail that you'll need to verify before you're officially on board. Once that's done, you'll receive an email every time we update the blog. Please don't hesitate to let us know if we can be of assistance. We appreciate your continued feedback and look forward to sharing even more wooden vehicle info in the coming weeks.

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC