I never cease to be amazed at the complexity,sophistication, and competitive drive possessed by those in America’s earlytransportation industry. With thousandsof horse drawn vehicle makers to measure up against, deciding to open up awagon shop in those days was not a suitable choice for folks lacking finances, marketing savvy, manufacturing prowess, or just plain guts. With so much competition in the nineteenthand early twentieth centuries, it clearly took more than a strong work ethic tobe successful. Ultimately, some didn’tlast more than a few months and others never produced more than a handful ofvehicles per year. A few beat the odds,not only surviving but manufacturing tens of thousands of wagons and westernvehicles annually.

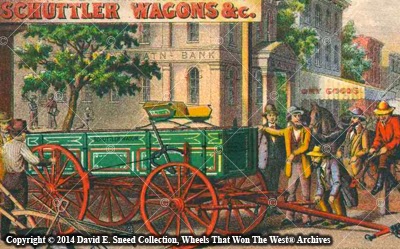

One of the most revered of those early brands isPeter Schuttler. Founded in 1843 inChicago, the company’s two and four-wheeled products were well known on thewestern plains and trails as well as remote mountains and towns. From freighting and ranching to farming and mining, the name ‘Schuttler’carried a strong reputation. It was a preeminentbrand delivering exceptional quality, strength, style, and innovation. During the late 1860’s, the company waslooking to grow its competitive edge and a young German emigrant, newly-arrivedin America, was destined to fill the bill. His name was Christoph Hotz. An talentedengineer and machinist by trade, it didn’t hurt that Peter Schuttler II was hisbrother-in-law. The founder andpatriarch of the firm, Peter Schuttler I, had passed away just a few yearsearlier and this new partnership with Christoph Hotz was destined to underscorethe Schuttler brand as an even more impressive western icon.

Beyond the family relationship, what really set Mr.Hotz apart was his inventive genius. Hewas full of ideas and instantly took to the wagon trade. Patents began to flow out of the Chicago firmand continued from the 1870’s until the time of his death in 1904. Among the inspirations credited to Hotz werenew concepts for wagon axles, end gates, standards, gears, tongues, andmore. The concepts just kept coming,with some destined to reappear well into the twentieth century.

To that point, many wagon enthusiasts are likelyaware of a swivel reach offered on Weber brand wagons and patented in 1922 byparent company, International Harvester Corporation (see above). A similar patent awarded to Christoph Hotzand Schuttler more than four decades earlier is less known. Nevertheless, it helped pave the way for future designs of this type. From the 1800’s through the early 1900’s, therugged terrain created constant problems for wagon travel. The racking, rocking, knocking, and twistingof the wagon wreaked havoc on every part of a gear – especially the reach or couplingpole. In the 1880 Schuttler patent (seebelow), Hotz engineered his own nineteenth century version of a rotating reach,allowing wagons to overcome challenges inherent in the roughest country. Effectively, the design reduced pressure on the reach, hounds, and other parts. To date, I’m not aware of any survivingexamples of this configuration from Schuttler, but just maybe, this blog post may helpus find one someday.

Just as a point of reference, by 1904, the PeterSchuttler Wagon Company is reported to have employed some 600 workers, turning out 20,000 wagons peryear†. By all accounts, the firm was aformidable foe but like so many others, the clock was ticking and within twomore decades, the doors were closed in Chicago.

†AmericanMachinist, January 28, 1904