Several years ago, I wrote a featurearticle on a half-dozen of the most legendary wagon makers in St. Louis. Even though some vehicle builders in MoundCity (as St. Louis was once called) were in business for close to one hundred years, automobiles and the Great Depression ended the dreams ofmost of them. Among the wheeled icons inthe city were two names with establishment time frames dating to the 1840’s and50’s. Today, both are tough-to-find examples fromAmerica’s first transportation industry.

TheEspenschied Wagon Company

Of all the early St. Louis-built wagons,there is likely none that gave mega-legends like Joseph Murphy greatercompetition than those made by Louis Espenschied. In the city directory of 1859, sixty-fivewagon makers were listed but only two paid for advertising space – Murphy andEspenschied.

Established in 1843, the EspenschiedWagon Company is eternally tied to the growth and history of America’s movementwest. From emigrant travel to the needsof the gold fields, freighters and army, Espenschied wagons carried a hugereputation for quality and dependability.

As part of that leadership, LouisEspenschied headed a group of four wagon makers that solicited the U.S. Army in1861, offering to build as many wagons as were needed by Union forces. Espenschied proposed construction of six-mulewagons with two-and-a-half-inch iron axles. The wagons were designed to carry five to six thousand pounds and the sameconfigurations were said to have been used by freighters traveling to NewMexico and Utah. Espenschied priced themat $125 each and pledged that they were better than Army regulationwagons. The proposal noted that thecompanies’ “many years’ experience in making Wagons for the Great Plains”enabled the four of them to craft the very best vehicles.

According to period reports, theproposal was immediately accepted and an order for 200 wagons was placed withinten days of the July 6th offer. No other bidding took place as the needs of the Civil War were urgentand the reputations of the four wagon makers – Louis Espenschied, Jacob Kern,Jacob Scheer, and John Cook were unquestioned. The wagons were promptly built and, by December of the same year,Espenschied made another proposal to the Army for another one thousand wagonsat the same price.

Like other makers of his time, Espenschied’sattention to detail not only showed in quality but also in designinnovations. In 1878, he was awarded a patentfor a built-in grease reservoir on the axle skein. That feature allowed the wheel to go longerperiods with less worry over the need for lubrication. Furthermore, in an 1882 company profile,Espenschied is also given credit for an even earlier advancement in wagondesign – the thimble skein. Dating tothe 1840’s, this invention was adopted by virtually all wagon makers.

Louis Espenschied passed away in 1887,leaving an estate valued at almost a half-million dollars (close to $13 millionin today’s money). Soon after, his firmmerged with that of Henry Luedinghaus, forming the Luedinghaus-EspenschiedWagon Company. Today, there are still afew existing Luedinghaus-Espenschied wagons, but an Espenschied dating to theoriginal firm has yet to be identified. Complicating this point a bit more is the fact that Luedinghaus appearsto have resurrected the stand-alone Espenschied brand for a brief time duringthe 1920’s. So, determining whether anEspenschied is a nineteenth or twentieth century survivor requires awareness ofthe product’s features and evolution.

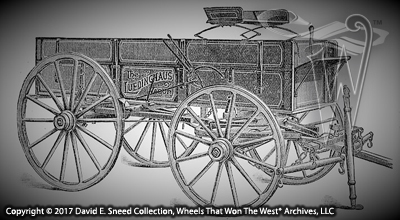

TheLuedinghaus Wagon Company

Henry Luedinghaus started his own wagonmanufactory in 1859. The LuedinghausWagon Company was located just across the street from his original partner inthe business, Casper Gestring, – pronounced “Guess-String” – founder of theGestring Wagon Company. In fact, theareas once occupied by Luedinghaus, Gestring, Espenschied, and Weber-Damme wereall within blocks of each other. I’vehad the privilege of walking the grounds of three of these builders and it’shard to imagine how challenging the competition was with each of them so closeto the other.

Henry Luedinghaus’ company distinguisheditself by making high-quality farm, freight, business, log, and lumberwagons. Within his second decade ofoperation, Luedinghaus was not only building to order but also maintained aninventory of wagons that could be purchased on-site. Around the same time, the company beganbidding on government contracts but, by this time, there were a number ofbuilders vying for the same business. An1880 Luedinghaus proposal of $61.50 per wagon was soundly beaten by the Austin,Tomlinson & Webster Manufacturing Company (Jackson Wagons). The winning bid from this Jackson, Michigancompany was $57. It was a priceadvantage that was hard for traditional makers to overcome – primarily becauseJackson wagons were built by state prison workers operating at a fraction of thelabor rate paid to law-abiding citizenry. Ultimately, these unfair practices would be frowned on by the courts –and the general public. For a number ofyears, though, the use of prisoners to gain a competitive edge was a serious problem for many wagonbuilders.

In spite of the challenges associatedwith nationwide competition, Luedinghaus continued to grow. One company motto was, “The wagon will speakfor itself.” It’s no wonder the vehicleswere so popular. Luedinghaus claimed tobe the first major manufactory to offer the exceptional strength andreliability of bois d’ arc (Osage Orange) wheels. All wood in the wagons was said to have beenthoroughly seasoned for two years before use and the paint was painstakinglyhand-brushed, not dipped. Dipping was afaster process but some found the resulting paint adhesion to be inferior.

At the 1904, World’s Fair, Luedinghausdisplayed a pyramid of eleven wagons. The massive exhibition dominated the competition and generated ahuge amount of publicity. The spectaclewas a physical duplication of the company’s official trademark and tagline thatproclaimed, “We Tower Above All.”

For a brief time in the 1920s and early‘30s, Luedinghaus built auto bodies, trailers, and even trucks. It was a valiant attempt to change with thetimes, but the challenges of the Great Depression were just too much towithstand. The firm closed its doors in1934.

|

| Shown in 1904, this tower of wagons wasa head-turning display for the Luedinghaus Wagon Company of St. Louis,Missouri. |

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC