FOR PETE'S SAKE

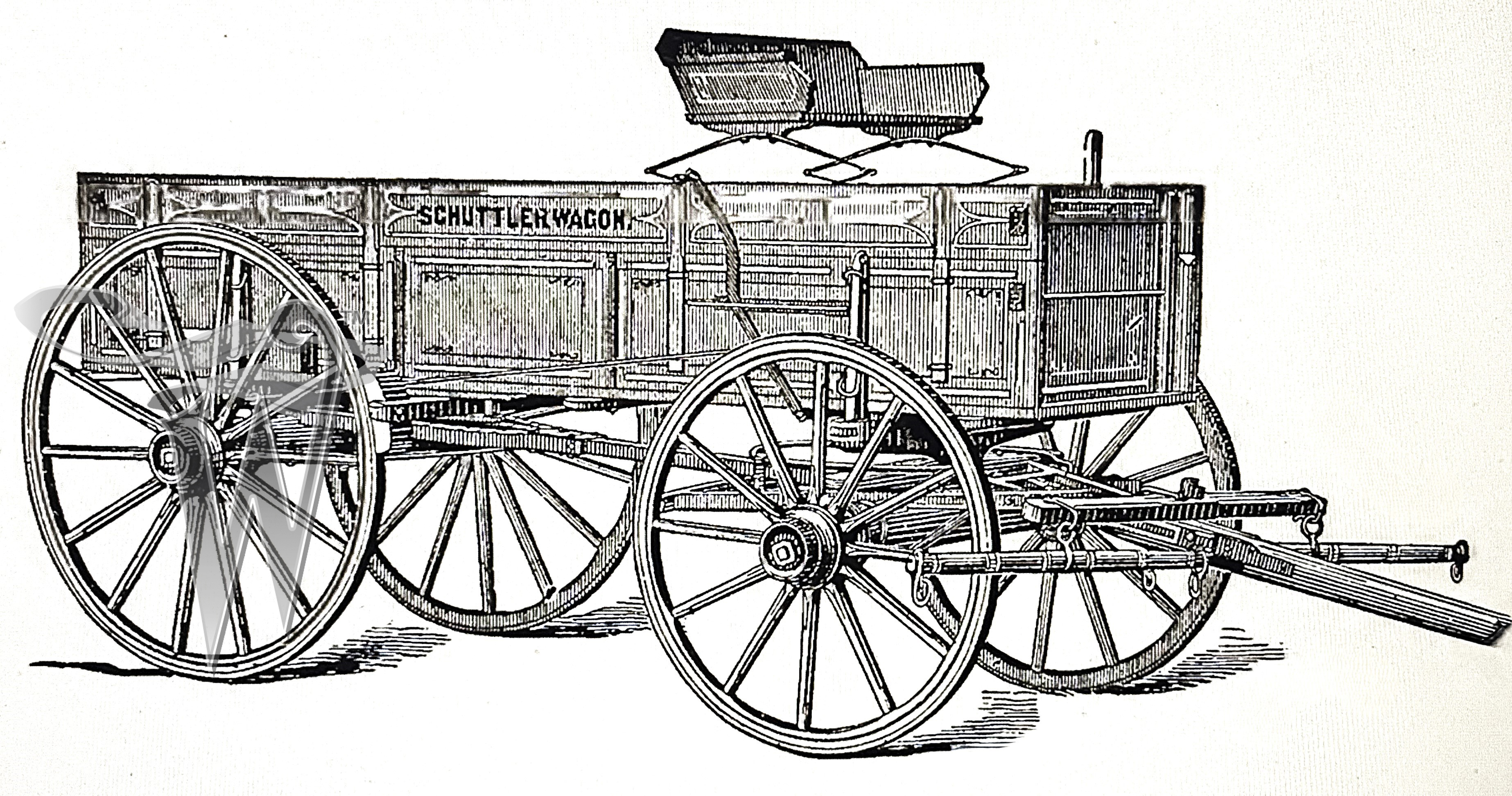

The Schuttler Wagon Story - Part 1

A while back, I was watching an episode of Gunsmoke on INSP. This particular show had Miss Kitty driving a team and wagon through the streets of Dodge City (S7, E3 - 1961). As she rode along, Marshall Matt Dillon approached. I immediately froze the video frame and jumped up to get a closer look. Alarmed by my hurried move, my wife looked up and said, "What in the world are you doing?" To which I sheepishly replied, "I gotta get a closer look at this wagon!" 😊Over the years, she's grown accustomed, if not resigned, to this type of abnormal behavior. The researcher and historian in me is always scanning the world for elements of our transportation past. What I'd spotted was the Studebaker logo on the side of the wagon box. While it wasn't the period correct logo or wagon box design for the Gunsmoke era, the scene was still intriguing because most westerns never show the wagon brand names that were so familiar to frontier pioneers. It not only added an extra element of depth to the program but it was refreshing to see this nod to one of the most historic names in the transportation world.

This image shows a Studebaker wagon from the Gunsmoke episode of "Miss Kitty" on INSP. For fans, this is Season 7, Episode 3 from 1961. Image courtesy of INSP.

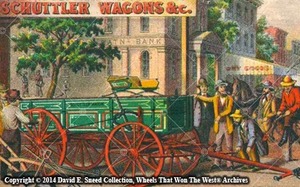

Dominating the country west of the Mississippi River, there were many other highly recognized western vehicle brands. What's less known are the stories behind those brands. Accounts of their hardships, losses, trials, and triumphs filled the pages of period newspapers and trade publications. Sharing those behind-the-scenes narratives not only helps us view the "good old days" with a clearer lens but, just maybe, these stories can provide some perspective on what it took to succeed in an industry that, too often, is mistakenly viewed as "simple." After more than thirty years of constant study, I can assure you it's an incredibly complex story, from the myriads of designs and engineering to the literal struggle to survive in a cut-throat trade.

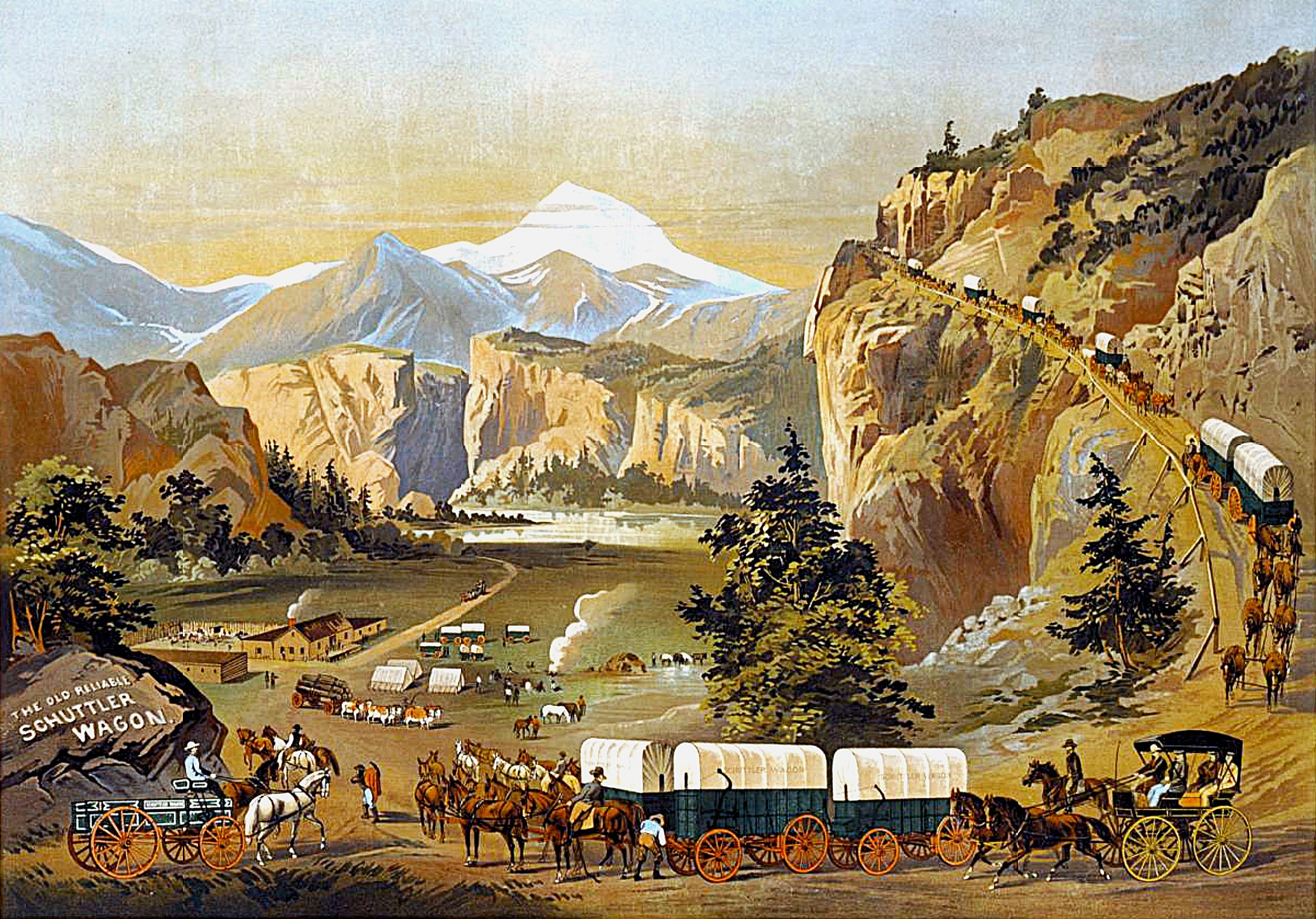

The push westward in 1800s America did more to accelerate competition and opportunity amongst vehicle makers than any other focus. Initially, though, the thought of "going west" was generally confined to parts of the eastern U.S. With no inner roads, no lines of communication, no real support of infrastructure, and little law west of the original colonies, traveling in unsettled regions was not for the ill-equipped or faint of heart. The terrain was harsh and unforgiving. Farther west of the Mississippi lay even more rugged country that would ultimately test the very mettle of men, mission, and machine.

Into this uncertain backdrop, thousands upon thousands of emigrants came to America. Each was looking for a better life, land, opportunity, and the freedom to embrace real liberty. They were the tired, the poor, the hopeful... Butchers, bakers, farmers, merchants, blacksmiths, wainwrights, wheelwrights, peddlers, opportunists - and dreamers. These were the nation builders, thrown together in a proverbial "melting pot" and destined to launch a world power.

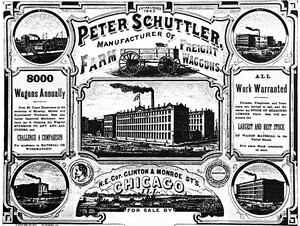

In 1834, Andrew Jackson was the U.S. President, Cyrus McCormick had just been awarded a patent for the reaping machine, huge Conestoga freight wagons were plying the country's first National Road, and the American transportation industry was rapidly growing in importance. Among the new arrivals that year was a young German by the name of Peter Schuttler. Ambitious and full of hope, Schuttler was just shy of twenty-two years old. With little food or provisions, he had managed to stay alive in a grueling fifty-four-day voyage across the Atlantic Ocean to America. After arriving in the new Promised Land, Schuttler's first employment came in a wagon shop near

In 1835, with little to show for the year's efforts, Schuttler pulled up stakes and moved farther west. His migration took him to the city of Cleveland- itself still a relatively young hamlet on the edge of the American frontier. He arrived just three years after a major cholera epidemic had killed fifty people in the city. He had scarcely hit town when trouble again came knocking. Maybe it was bad water or infected food, but somehow, he contracted a near-deadly case of typhoid fever. A bacterial infection of the intestinal tract, typhoid was especially feared since, at the time, there was no effective treatment for the disease. The miracle discovery of antibiotics was still more than a century away. For Schuttler, this battle made the challenges of his earlier sea voyage seem tame. This was a life-threatening fight that left him barely able tofunction, much less work. He suffered for six long months. Slowly, his health did return, and with it, his enthusiasm also rebounded. He started a small wagon shop, but the realities of a new life in America continued to throw their own curves. He had put his heart, soul, and finances into building sleighs for the surrounding trade. Unfortunately, finding customers proved to be difficult. Local interest in his wheelless runners was as cold and indifferent as the ground they sat on.

By the time the depression of 1837 struck, Schuttler had hit rock bottom. With only ten shillings left to his name, he packed his few belongings and moved even farther west to Sandusky, Ohio. The transition was an improvement, but after another six long years of hard labor, he still had less than $400 to show for his efforts. By now, Schuttler had married Dorothy Gauch, a native of Prussia, and had two children... a daughter, Catherine and a son, Peter Schuttler II. Determined to provide for his family, Schuttler did the only thing he knew to do. He kept moving west, even closer to the frontier. Little did he know but a fortune was about to be discovered in California and his fierce attention to detail would be just what travelers were looking for!

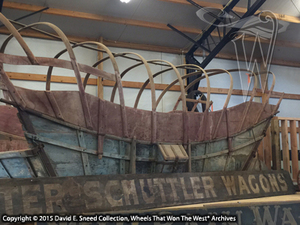

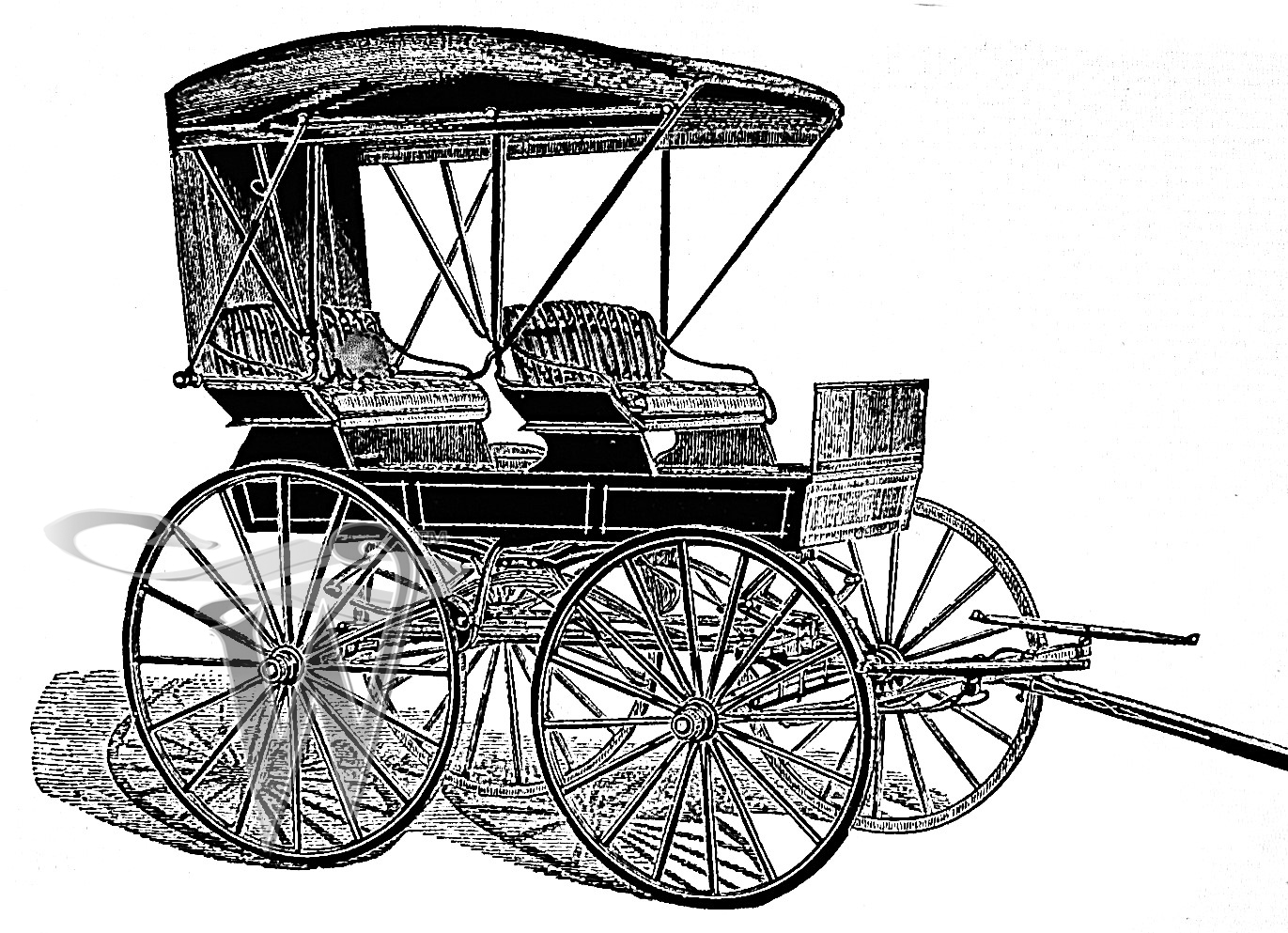

An extension top spring wagon made by the Peter Schuttler Wagon Company in 1879. Schuttler vehicles of this type and from this timeframe are extremely rare to come across in the 21st century.

Next week, we'll look at the second portion of this three-part story. There's a lot about this early maker that's rarely discussed so, get ready to discover some things that add even more to the rich history of this brand. One more thing... if you're fortunate to own a legacy-laden Schuttler or have a related story, drop us an email. We'd love to hear from ya.

Ps. 20:7