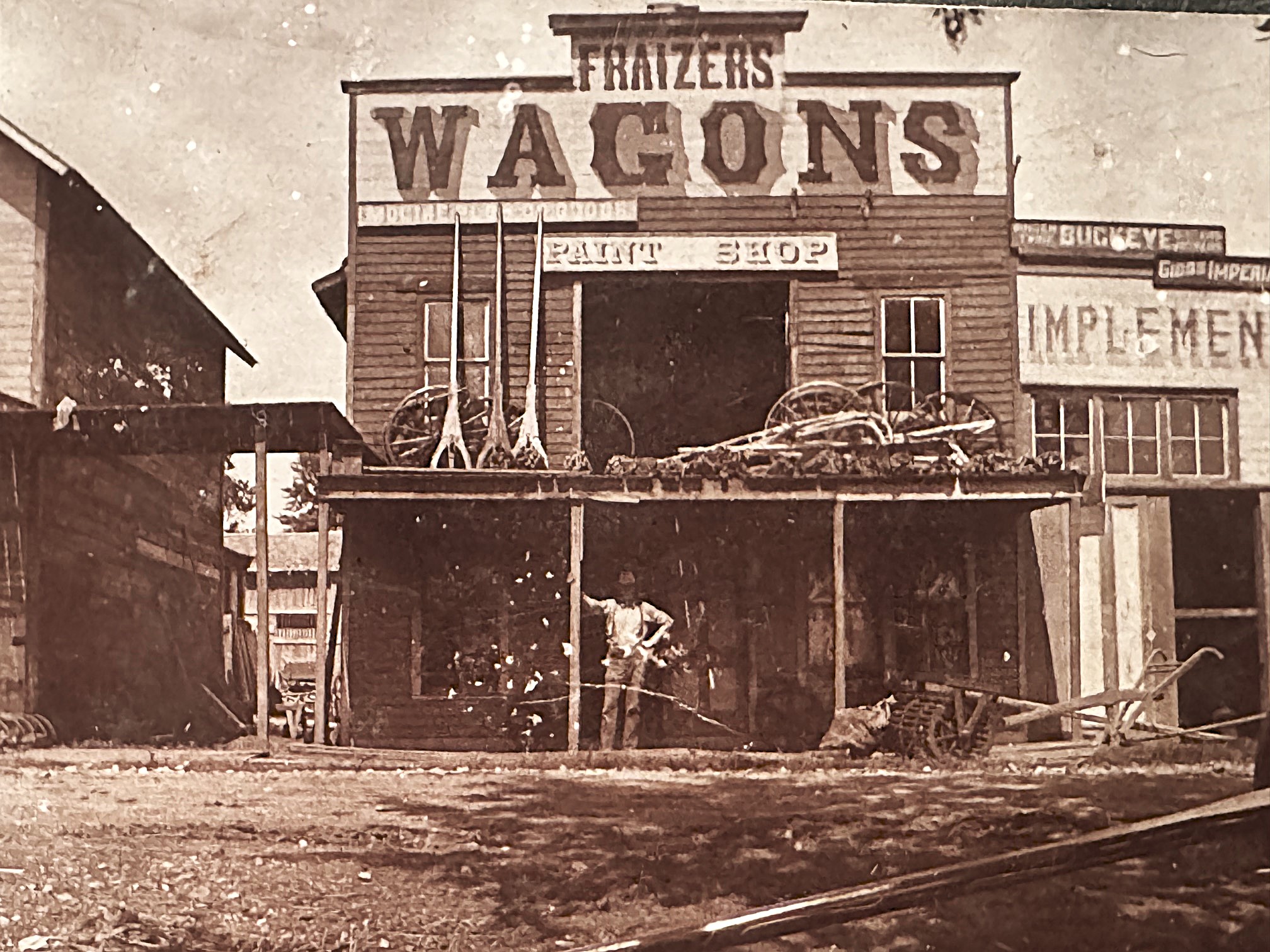

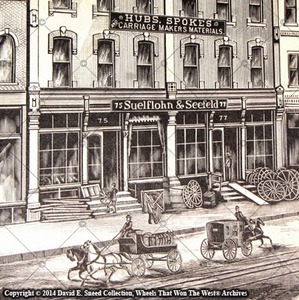

Among the timeworn, original images in our archives are hundreds of frozen moments depicting early wagon, carriage, and blacksmith shops. These original, unpublished portraits are stark reminders of days-gone-by and they're full of character, curiosity, art, and intrigue. Each was a forerunner of early machine, body, paint, carpentry, bicycle, or even automotive endeavors. Proficient in wood, paint, and metalwork, many of the folks working in these places were producing products that became staples for a community, region, or the country as a whole. Still other photos of these early entrepreneurs are the only-known record of a forgotten brand's humble roots and hopeful dreams.

This 1860s-era image shows a wagon maker with two dozen employees. The work was hard, the days were long, and more often than not, carriage and wagon factories were operating six days a week.

The wagon-making and repairing that took place inside these old shops required a world of tools, hardware, and raw materials as well as plenty of patience and skill. The equipment needed for the job ran the gamut between forges, blowers, hammers, anvils, mandrels, swage blocks, spoke tenoning machines, lathes, planes, drills, saws, draw knives, travelers, vises, tap & die sets, compass sets, wrenches, tire upsetters, brushes, paint, varnish, clamps, wood benders, hub borers and boxing machines, hydraulic skein and wheel presses, tire benders, and so much more. Today, there are still a few specialists that practice portions of this near-lost craft. Much larger, though, is the collector crowd; countless folks scouring the country, searching for rare vehicles, tools, images, ephemera, advertising, and other period connections to America's first transportation industry. Each of these pieces tells the tale of a way of life, day in time, and massive industry that's forever gone. Likewise, individually and collectively, they're the only surviving witnesses to a time when wheels were wood and horseflesh ruled the road.

Another piece of equipment in our collection is a spoke-tenoning machine that hearkens back to the 1860's. With multiple height and length adjustments, this apparatus is engineered to work with wheels over sixty-inches in diameter (height). The saw horse-style design makes it somewhat portable, more easily adapting to different space needs within smaller shops.This is also one of numerous pieces of early transportation equipment profiled on our exclusive "Making Tracks" print.

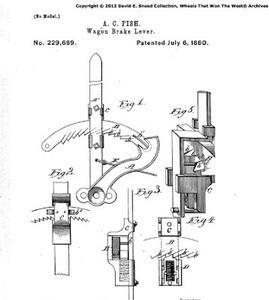

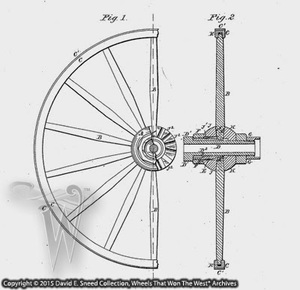

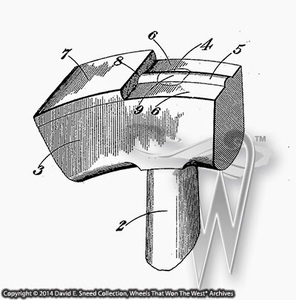

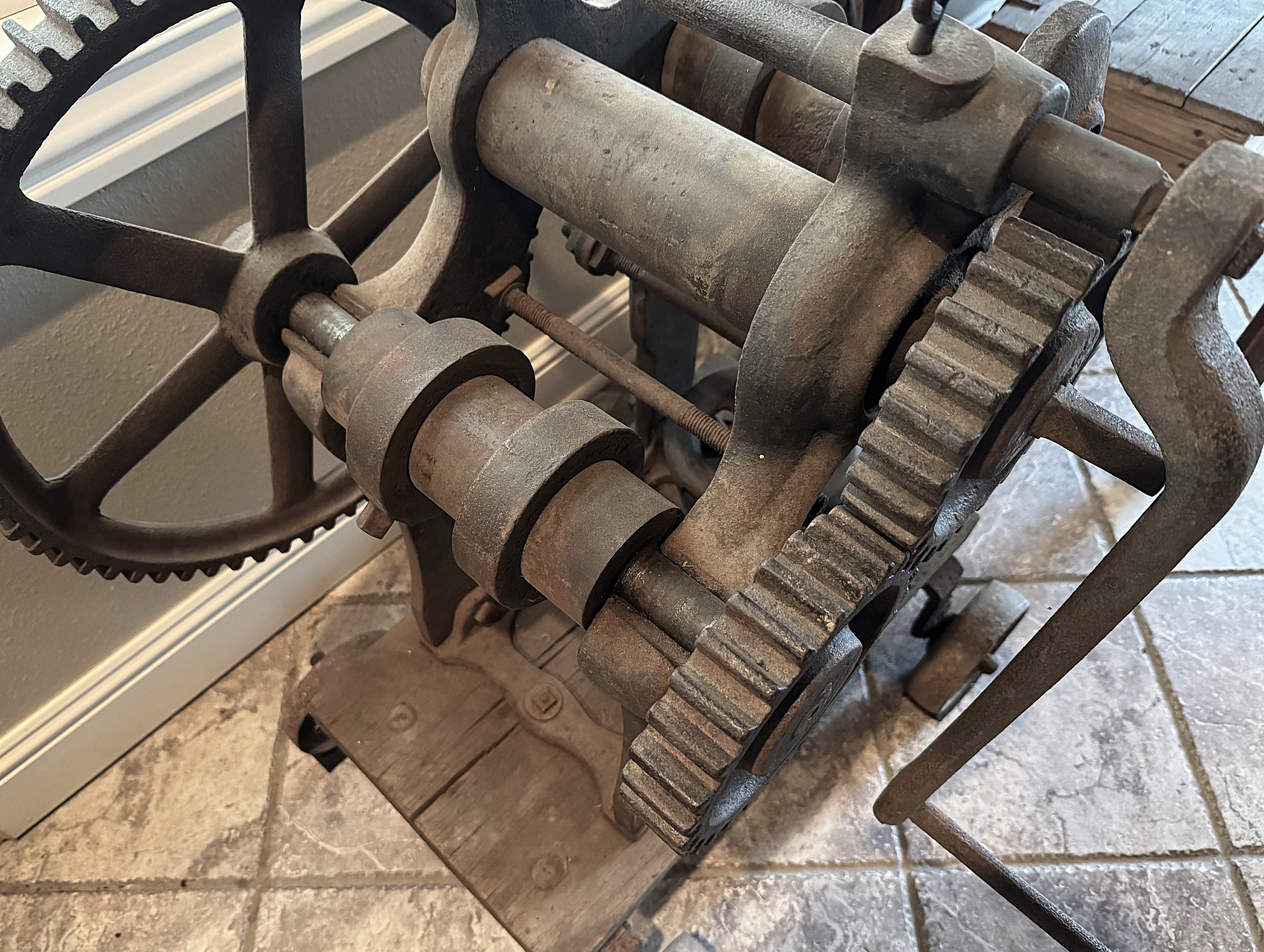

Still more equipment amongst the myriads of wagon-making tools is a tire upsetter. This device is made to shrink a heated section of a wagon tire, allowing the subsequently reduced tire diameter to be re-set on the wheel, effectively firming up the entire structure. Since the wheels are the foundation of the vehicle, it's important to ensure the soundness of a wheel and tightness of a tire before use. So, how does a tire (the metal band encircling the wheel) get loose? Well, with time as well as environment conditions and use, a wagon tire can be continuously hammered by load and road pressures like rocks, uneven terrain, and even rubbing of the wagon box. This process of wear can actually change the shape of a tire, spreading it out and even cupping the underside of the metal. In cases where the tire is driven too much out of shape, it's possible that a new tire will need to be used as a replacement. On top of that, since wood is hygroscopic - meaning it both absorbs and loses moisture - the wood will shrink at times. That will cause the wooden portion of the wheel to draw away from the metal tire. Eventually, the tire can become loose and need to be retightened. While soaking a wheel in a body of water can help expand the wood and tighten things, it's only an emergency effort as the wheels will reassume the loosened state once the water has evaporated. Unfortunately, repeatedly soaking wheels in water is not friendly to the wood fibers or any glue that had been used in the connected parts. Extended use of this shortcut can also cause wood to crack and even rot.

To help combat these concerns, in the 1800s and early 1900s, different technologies were introduced to help keep the tires secure. Like many problems in life, though, there is no cure-all. Environmental conditions as well as regular use will constantly push the tire to become loose. Tire tightening was a common maintenance issue during the horse-drawn era, much the same as monitoring air pressure and lug nut tightness is on automobiles and trailers today. Some makers used tire bolts to help hold the tire to the felloes. However, even this technique is not without its own issues. Over time, it can actually pull the felloes away from the spokes and or hubs, ultimately creating the potential for a very unstable wheel. With this said, there were a few manufacturers who used oil grooves in the felloes to help combat loose tires while still using tire bolts.

Another interesting item in the Wheels That Won The West® collection is a painter's kit for pinstriping. Long before decorative brush strokes were highlighted on classic cars and trucks, the schooled hands of skilled artisans from the horse-drawn era were applying intricate flourishes, murals, and decorative lines to wagons, carriages, and coaches. This head-turning street art was accomplished with a host of different techniques. Specially-contoured camel hair brushes, varnish strainers and stands, body trestles, gear horses, putty knives, brush keepers, sandpaper, paint strainers, gold leaf, and much more were among the stocks in trade for this highly-specialized occupation.

I'll highlight one other item in our collection that's not a piece of old equipment but it does often stop visitors in their tracks. It's a four-foot by six-foot shadowbox display. Inside the framed case is a background made from an 1860's-era map with various cattle drive, emigrant, railroad, and staging routes in the Old West. Additionally, we've posted locations of a number of major wagon makers and notable events from the 1800's to help show how all of this transportation history tied in with historic western happenings. Similarly, a number of images and outtakes from early emigrant letters are posted on raised stand-offs, giving the entire piece a 3-dimensional feel. While the map points viewers in a variety of directions, the year-specific data helps put the entire exhibit into a relatable western history experience.

More to come. FYI... We're working on a way that folks can sign up for notifications to all of the updates to our Blog and Article sections. Stay tuned...

Ps. 20:7