With so many individual elements comprising a vintage wagon wheel, the design is considerably different thanmost modern day vehicle wheels. Without proper maintenance, the passage of time as well as the sheer number of separate parts in a wagon wheel can wreak havoc on the soundness of the piece.

Binding a wooden wheel with a steel tirehas proven to be a good way to keep the entire structure solid. Clearly, as long as the wood doesn’t move toomuch, it works extremely well. However,whether it’s through temperature or moisture variances or forced displacement,the challenge is that wood does move. For wheel and wagon makers of old, the chore of keeping steel tires onwooden wheels was a never-ending job.

Holding the tires on the wooden rims orfelloes (pronounced as ‘fell-ohs’) was approached from a number ofdirections. From tire bolts and rivetsto nails, wedges, pins, oil, water, rawhide, and a host of other remedies,there was no shortage of ideas to help solve the short and long-termproblem. Even arguments over whetherhot-setting or cold-setting tires was best were continually shared in businesscorrespondence and industry news. (I’llcover more on these technologies in a future blog)

Not long ago, while doing research on aregional wagon maker in Iowa, I ran across yet another method of securing atire to a wheel. In 1895, WilliamO’Brien submitted his idea to the U.S. Patent Office. Unlike many hopeful patentees, O’Brien’snotion apparently did make it off the drawing board and into production. While it’s not currently known how long theinnovation was used, period reports seem to indicate the idea was successfulfor a number of years.

|

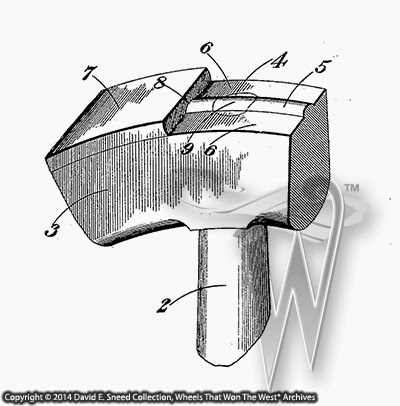

| This 1895 patent illustration shows the unique way O’Brien wagon tires were secured to the wooden wheels. |

As shown by the illustration above,O’Brien’s concept involved the creation of a continuous rib or bead along thetread surface of the felloes. Thisraised bead was fitted into a matching concave groove in the underside of thetire effectively ‘locking’ the tire onto the felloes. During the hot-setting process, the tire washeated sufficiently to expand over the bead. Once it cooled, the tire shrank to fit the beaded felloe, effectivelysecuring itself to the wheel. As long asthe hub, spokes and felloes remained reasonably tight and unitized, the tiregroove would stay seated on the rib encircling the wheel.

Ultimately, this discovery is one morefeature that may prove helpful in the identification of some O’Brien brandwagons. I say ‘some’ because there wasmore than one O’Brien wagon brand and, even survivors of the correct make maynot have been produced during the timeframe of the patent.

Just like the bone-jarring hardshipssuffered by countless wooden wheels, it seems the ordeals of identification arealways there; shifting, shaking, and testing our resolve to hold onto our pastand keep it all together.