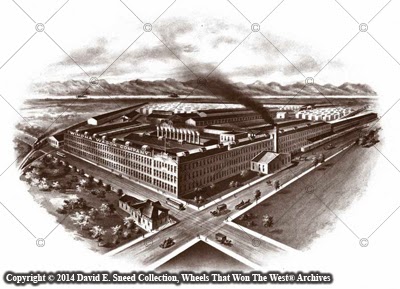

Similar to today's automotive industry, America's early wagon makers spent a lot of time talking about how well their products were received by the public. These claims were especially hard to dispute when the larger firms openly shared the number of vehicles they built each year. Studebaker, of South Bend, Indiana, was among the largest. Far from the traditional corner blacksmith shop, Studebaker - and many others - were ultra-efficient, aggressive manufacturers that quickly learned the power of marketing and a solid distribution system. So successful was this brand that, by 1890, the company is said to have employed some 1400 workers, turning out a new wagon every six minutes.1 It's a contention further reinforced by company assertions that in the decade between 1897 and 1907, they built and sold over a million vehicles.2

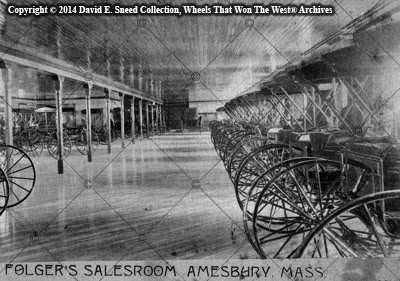

The vast number of wood-wheeled wagons that major manufacturers like Peter Schuttler, Studebaker, Winona, Kentucky, Weber, Bain, Mitchell, Stoughton, Mandt, Moline, Jackson, and so many others wholesaled can easily overshadow specific sales examples at the retail level. Truth is, for record numbers of these vehicles to have been built during the course of any year, they had to be flying off of the proverbial dealer shelves. While period newspapers and other historical accounts often provide numbers of wagons and emigrants moving west, specific details showing the successes of product turnover at the retail level are often hard to find.

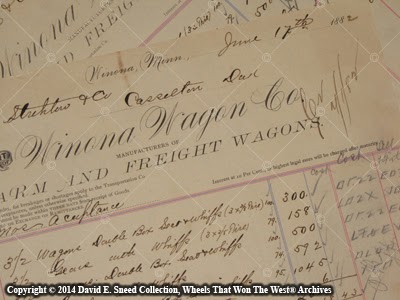

1882 Winona billheads

To that point, I recently ran across a pair of 1882 billheads from the Winona Wagon Company that shed a mere pinhole of light on the feverish retailing of wagons during this timeframe. Both invoices are made out to a single dealer - Strehlow & Company in Casselton, Dakota. Posted a full seven years prior to North & South Dakota becoming individual states, these pieces show nearly sixty wagons and gears sold to the local dealer in less than two months' time; all of this to a tiny population of about 400 folks. Taken as a sampling of an entire year, it's quite possible that this ultra-small-town dealer could have been responsible for at least 200 to 300 wagon/gear sales in just twelve months. With thousands upon thousands of local and regional trade areas throughout the U.S., these bits of information (even for extremely localized districts) help emphasize just how lucrative wagon sales could be. It's a big reason the industry was so fiercely competitive; from price wars to timber buy-outs, patent lawsuits, and other extreme measures. Many dealers - sometimes referred to as agents - hung out a shingle for multiple wagon brands as a way to 'lock up' sales and minimize interference from other local sellers.

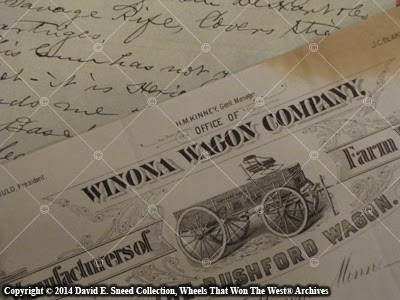

1882 Winona Wagon Co. letterhead

During the same year of 1882, the fledgling Winona Wagon Company (Winona, Minnesota) was just three years old. It was the successor to the Rushford Wagon Company of Rushford, Minnesota. Within a few years, Winona would become a force to be reckoned with by even the largest of vehicle builders. The firm held multiple patents while also becoming well-known for its high quality farm, freight, military, fruit, and Mountain wagons as well as header gears and even sheep camp wagons. Today, the brand is still extremely popular with collectors and enthusiasts.

From individual corporations to the entire industry, the competitive focus within the world of horse drawn vehicle builders set the stage for the automobile business in almost every respect. Crucial lessons regarding management of raw materials, distribution channels, manufacturing efficiencies, advertising tactics, advancements in engineering and new product innovation, quality practices, and other all-important drivers of brand perceptions were opening up even more opportunity within America's free enterprise system. From coast to coast, the business of transportation was growing up and, ultimately, only the strongest would survive.

1 "The Great Southwest", vol 2, no. 9, p.13 (September 1890)

2 Wheels That Won The West® Archives