History has given Henry Ford a lot ofjustly-earned credit for building and selling automobiles so affordably thatthey could be enjoyed by the masses - not just those with deep pockets. Longbefore Mr. Ford’s entry into the transportation business, though, there werecountless other horse-drawn vehicle makers with a similar business plan; onefocused on creating a quality set of wheels that individuals could afford inbusiness and pleasure. While Fordencountered numerous challenges in his commitment to building a bettermousetrap, America’s earliest transportation pioneers were also continuallyfaced with the trials of maintaining a successful business. Manufacturing requirements, raw materialavailability, a viable labor supply, marketing, sales, warranties, resalevalues, loyalty, competition, distribution channels and a myriad of other issueswere dealt with daily.

Far from being small-time businessneophytes, many early makers of vehicles used throughout the U.S.were educated and business-savvy. Evenin the 1800’s, some of the biggest wagon builders were finishing tens ofthousands of wagons per year. In fact, duringStudebaker’s peak production years, the firm boasted that it finished a vehicleevery six minutes. The legendary brandalso claimed to have built – and sold – a million wagons in the decade between 1897and 1907†. By any measure, those areimpressive numbers. Equally noteworthy isthe mechanization and repeatable factory processes that were employed toaccomplish such feats of mass production.

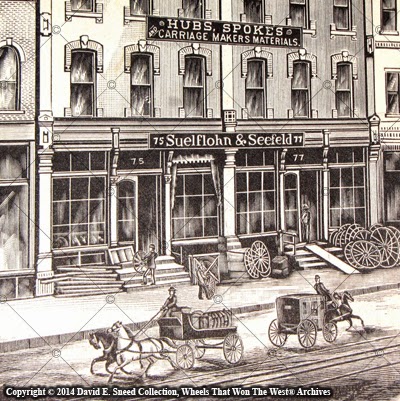

While some small blacksmith shops mayhave still been hammering out hand-forged iron work in the late 1800’s, most westernvehicle builders of any size had recognized the value of time as it related toprofits. Hence, as the turn of the 20thcentury approached, these larger manufacturers may have been engaged in forgingsome parts but they were often using cast and pre-formed pieces available fromwholesale outlets.

As pointed out in Thomas Kinney’s book,“The Carriage Trade: Making Horse Drawn Vehicles in America,” these earlyvehicle makers clearly recognized that ‘time is money.’ As a result, there were entire subgroups ofcompanies that sprang up to provide equipment, parts, and supplies to assistwith more rapid production of quality western vehicles. This was not just working faster, it wasworking smarter and, in most cases, delivering a higher quality product in amore timely manner. At its core, thisinvolved very similar business thoughts as those covered in some of the mostelite corporate boardrooms of today.

A growing agricultural economy alongwith the Civil War, with its massive need for vehicles, did its part in drivinginnovation and productivity. Numeroustechnological advances and specially fabricated machines were introduced duringthis timeframe. Patents for automaticaxle lathes were issued as early as the 1860’s with designs committed togreater accuracy, speed, efficiency, and productivity.

Eventually, other instruments engineeredfor even higher production capacities were also introduced. Heavy equipment like automatic spoke lathes,spoke throating machines, belt polishers, and felloe sawing machines werejoined by automatic hub mortisers, automatic wagon box floor nailers, and wagonbox boring machines for gang drilling all of the holes at one time in the boxsides of a wagon. Each innovation madethe production process more efficient, vehicles more affordable, profits moreattainable, and customers more satisfied with the final product. Collectively, it was a commitment toexcellence that’s still reflected in rolling works of art all over the country.

† Wheels That Won The West® Archives, www.wheelsthatwonthewest.com