The Peter Schuttler Wagon Company, Part 3 of 3

The Legacy

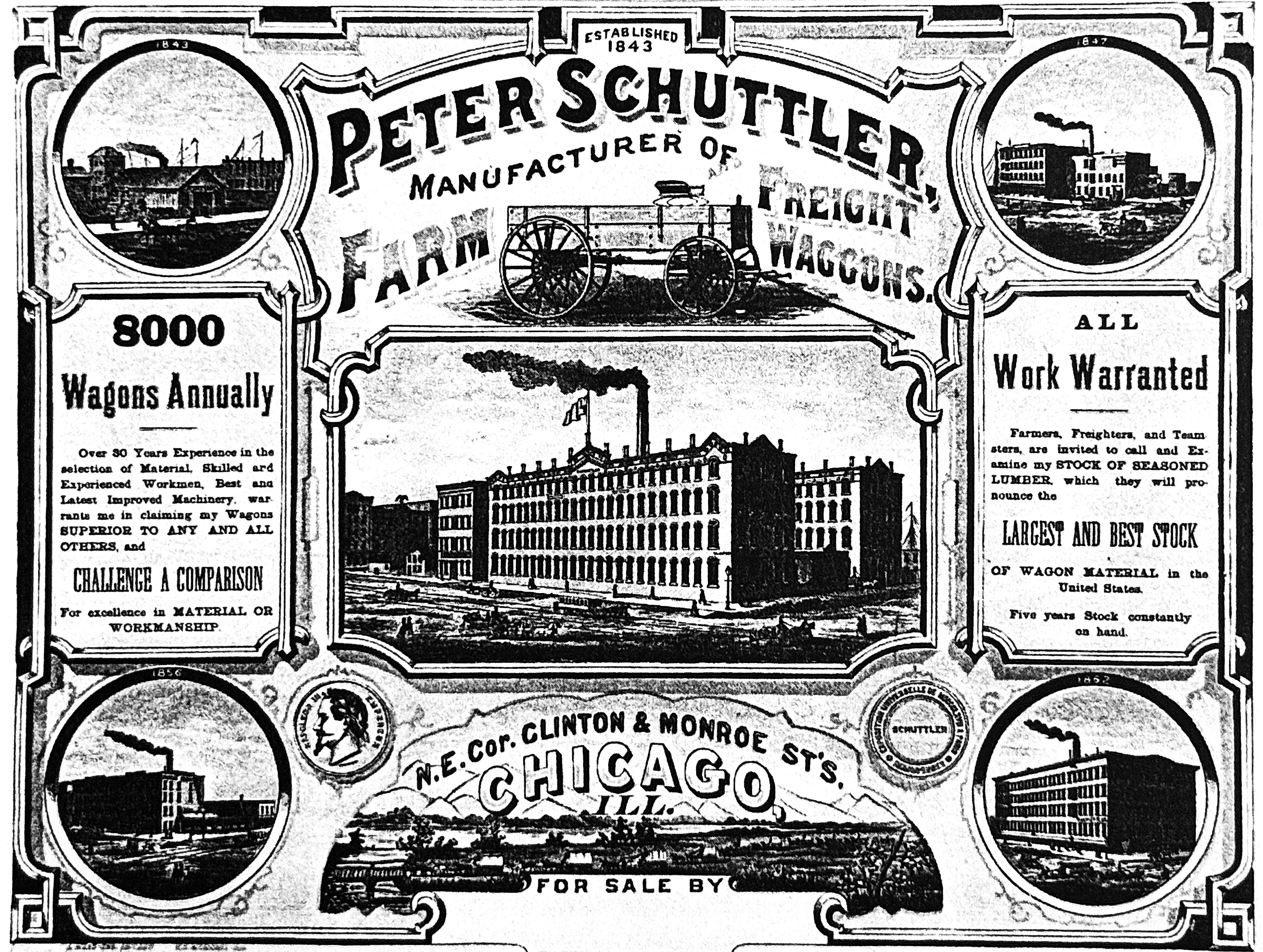

As the Civil War continued, Schuttler's popularity didn't go unnoticed by the U.S. Government. In fact, according to an 1884 report in the History of Cook County, Illinois, by 1857, Peter Schuttler "had one of the largest establishments of its kind in the West."

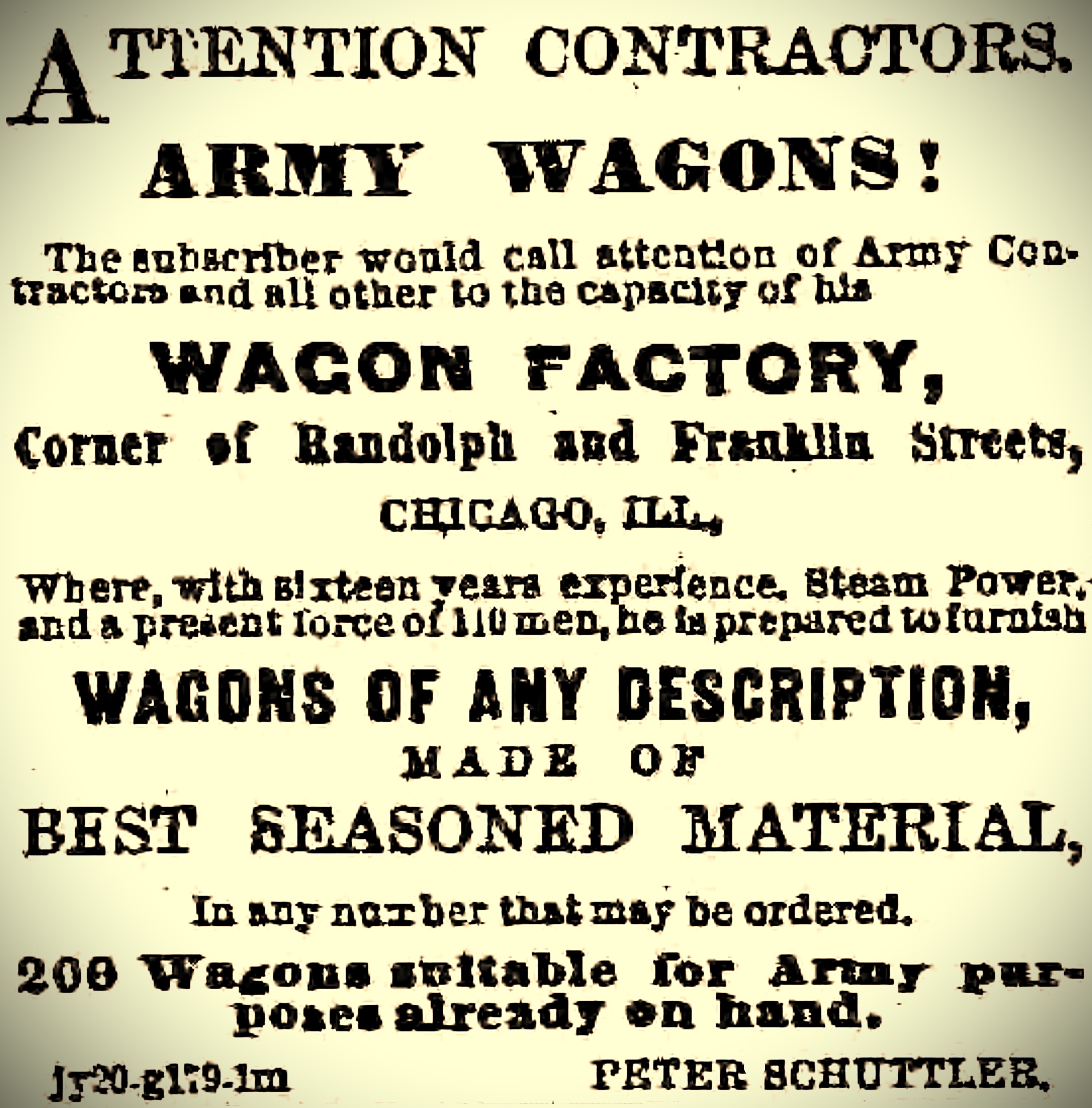

In 1861, the elder Schuttler was just shy of fifty-years-old and well-seasoned in the promotion of his brand. He took out an advertisement letting the U.S. Army know that he was ready, willing, and more than able to help with the Union's efforts. It was equal parts public relations and patriotism.While there is some evidence that Schuttler built cannon trucks and army wagons for the Union, other reports indicate that while he was eager to supply the wagons, eventually, there was a catch. According to an 1868 report, army brass wanted him to build wagons according to their specifications and he was adamant that his own designs would fare much better. For too long, Schuttler had tirelessly worked to forge his reputation and, for too long, he had waited for the world to recognize his efforts. His stubborn commitment to quality cost him army sales, but it earned him an absolute fortune from the rest of the country.

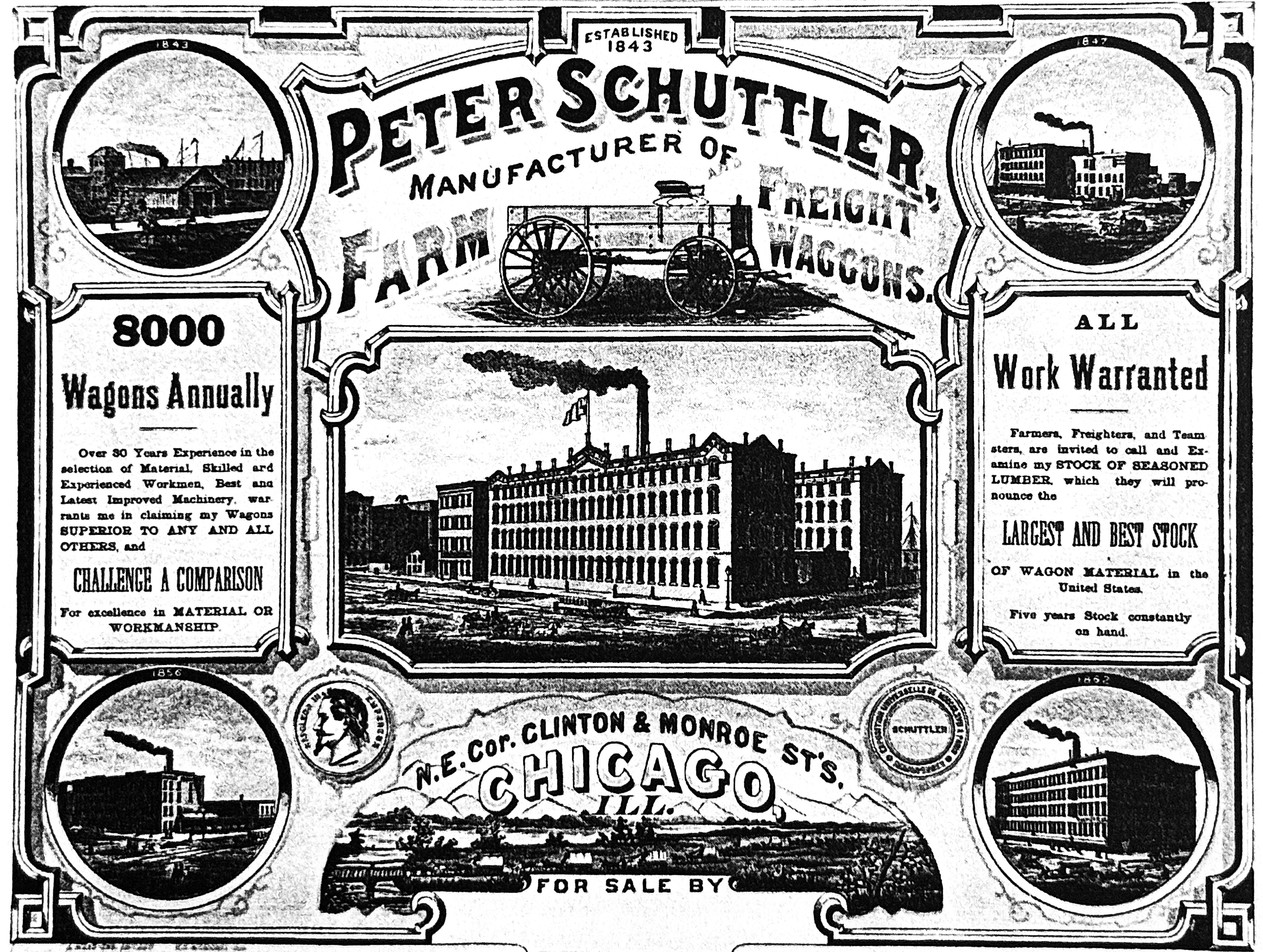

Introduction page from an 1898 Peter Schuttler catalog.

As his reputation spread, Schuttler enjoyed the rewards of hard work. He had come from humble beginnings with virtually no financial means to a place of international stature and significant reverence among his peers. Competitors like the legendary Studebaker Brothers in South Bend as well as other major builders such as Mitchell and Milburn, who also made the early transition from horse-drawn vehicles to automobiles, saw his company for the giant that it was. With literally tens of thousands of vehicle makers in

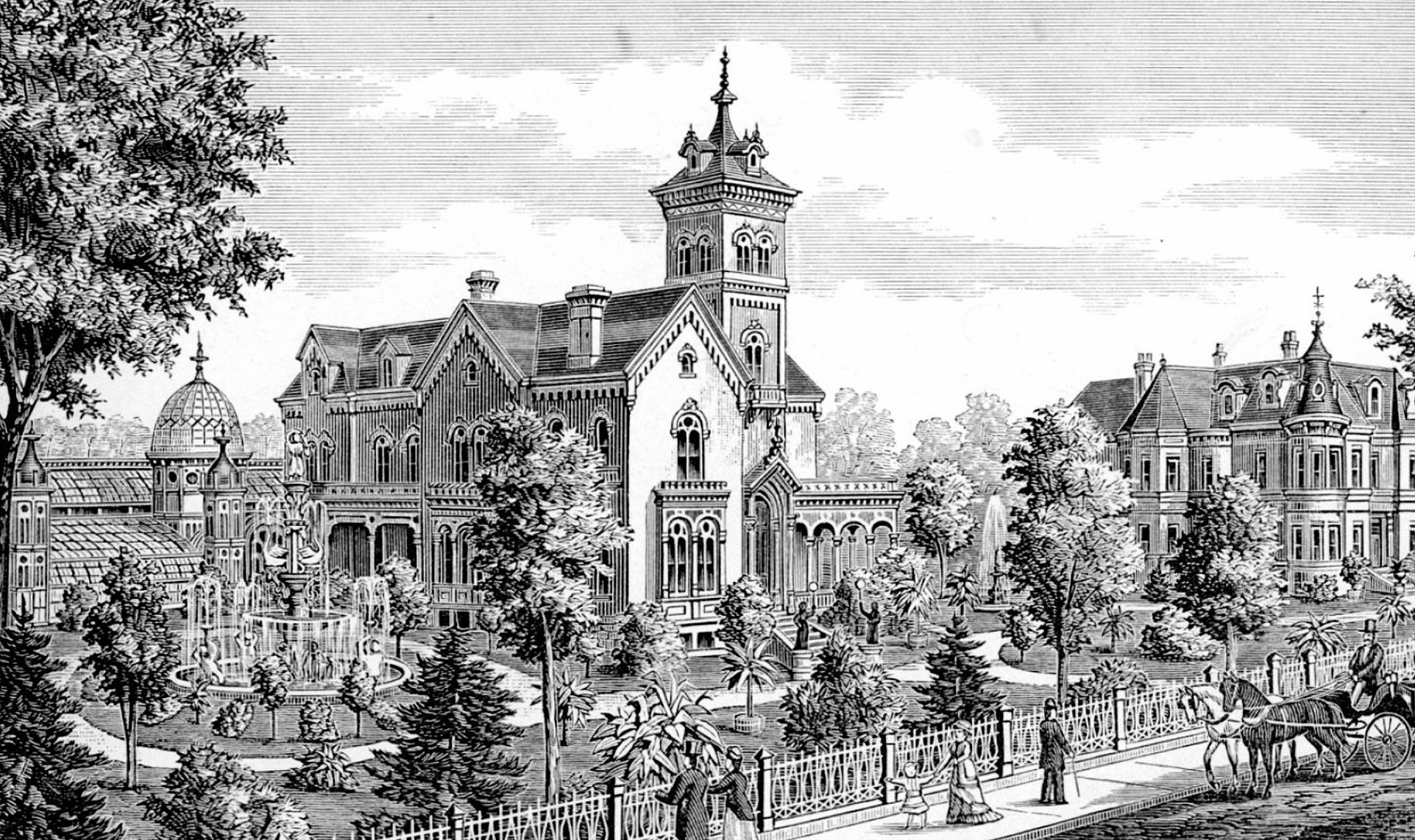

In 1865, the home that Peter Schuttler had been building for three years was finally finished. It was an impressive landmark and architectural wonder. So distinct was the structure that the ChicagoTribune hailed it as "the most magnificent building in Chicago." Others considered it the "finest house west of New York City." In that final Civil War year, the mansion had cost a half million dollars to build and furnish. That's the equivalent of putting more than $9.6 million into a home today! Clearly, no efforts were spared in its construction. It was destined to be a respite and gathering place for the world's nobility and America's richest elite. Sadly, the elder Schuttler would never know its full grandeur, as the year 1865 was also to be his last.

A circa 1870 illustration of the Schuttler mansion completed in 1865. Image courtesy of chicagology..com

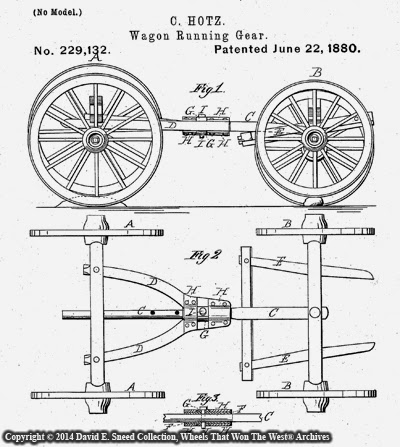

After Schuttler's passing, his son, Peter II took over the business. He was only twenty-four but had been groomed for the transition and was well up to the task. Three years later, in 1868, the young Schuttler brought his twenty-six-year-old brother-in-law, Christoph Hotz, into the organization as a full partner. Hotz was married to Catherine Schuttler, Peter II's sister. Hotz's architectural, drafting, and engineering genius further reinforced the leadership status of this Chicago megabrand. Developing patents on wagon tongues, king bolts, reaches, felloes, standards, end gates, running gears, and more, the brand was a force to be reckoned with.

The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 was devastating to the entire city. Image from the Wheels That Won The West® Archives.

Like most larger corporations today, the drive for continuous improvement and product excellence was a strong company mission. It's a good thing because, six years later, the firm suffered another massive loss from still another out-of-control inferno. This event would not be downplayed or forgotten by anyone. It was the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Whether it was caused by Mrs. O'Leary's cow or some other source, the overwhelming tragedy affected everyone in the city. Raging from Sunday evening, October 8th until Tuesday, October 10th, the fire destroyed five square miles of the city, killing three hundred folks, leaving over 100,000 people homeless, and causing more than two hundred million dollars in damage (That's over $5 BILLION in today's dollars). By this time, though, the Schuttler business was solid. With a national and international distribution network, the company took just seven months to rebuild and ship their first load of wagons. The transition allowed them to redesign the entire factory while focusing efficiencies on the latest innovations and technical tools. Soon afterward, they also added a hub and spoke factory to their operations. It was a vertically integrated supply shift that helped prepare and position them for another five decades of successful leadership. The factory grounds had expanded to encompass ten acres while employing more than two hundred craftsmen with a capacity between seven and eight thousand wagons per year.

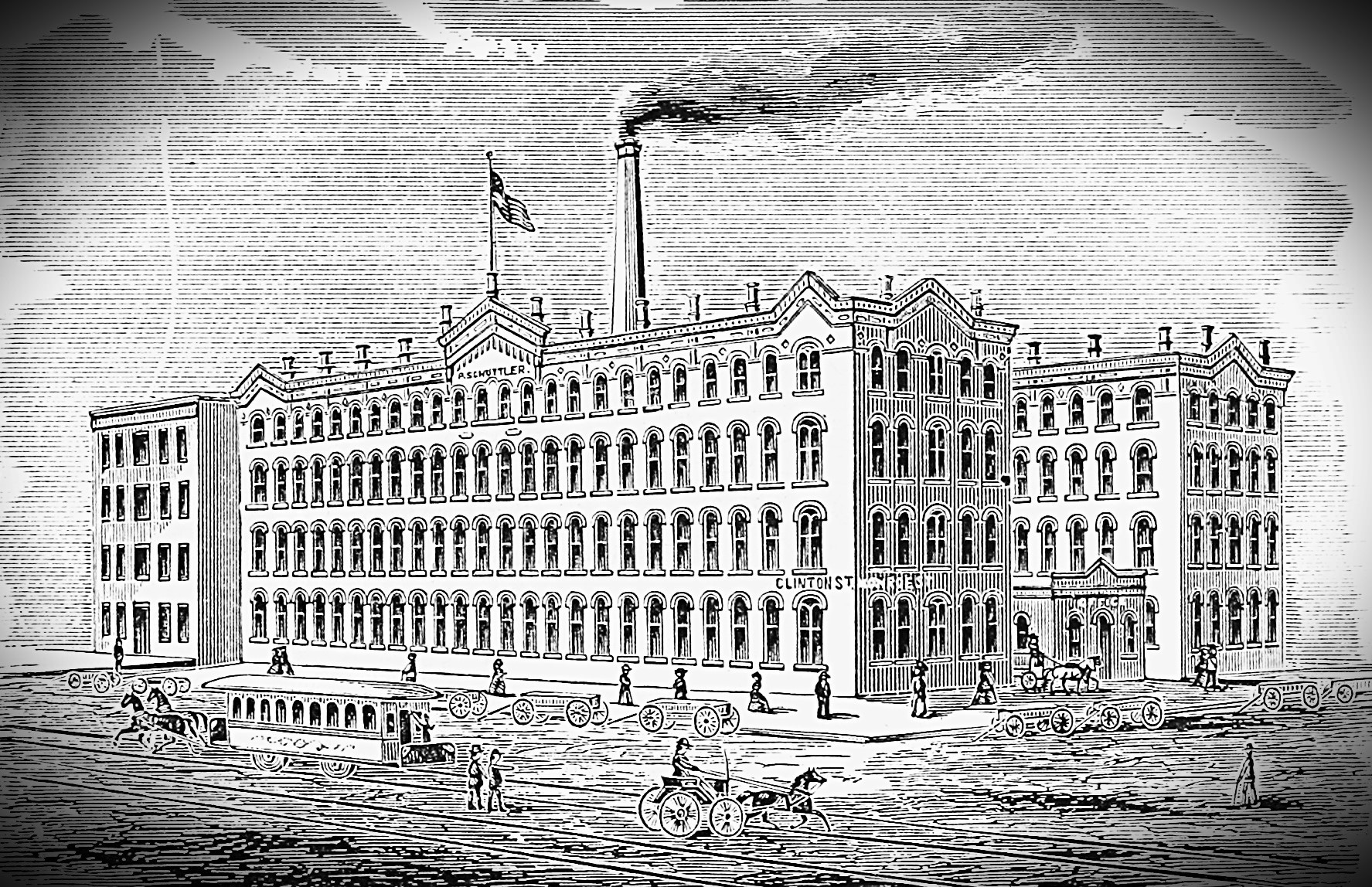

By the mid-1870s, Schuttler was a transportation manufacturer to be reckoned with. Wheels That Won The West® Archives.

Just to reinforce the powerhouse nature of the Schuttler brand during this segment of history, it's interesting to note that just one year after the widespread devastation from the 1871 Chicago fire, Peter Schuttler II married Wilhelmina "Minnie" Anheuser. You might recognize Minnie's father. He was Eberhard Anheuser who was partnered with Adolfus Busch in the beer-making business. Obviously, along with being a young transportation tycoon, this also made Peter Schuttler II the son-in-law to a rapidly growing beer dynasty. Likewise, Mr. Busch had married another of Eberhard Anheuser's daughters, Lilly, in 1861. After the Civil War, Adolfus joined his father-in-law's business, then known as the Anheuser brewery. By 1879, the company was renamed Anheuser-Busch. Interestingly, among the specialty trade vehicles that Schuttler designed and built were Beer Roll wagons. These customized rigs were designed for easy loading and unloading of heavy beer kegs. They are among the rarer Schuttler vehicles to come across today.

In 1878, while the wagon brand continued to be known as Peter Schuttler, the legal name of the firm became known as Schuttler & Hotz, with Christoph Hotz becoming a full partner. The 1880s saw numerous patents awarded to the brand as they sought to continually outpace competitors. Far from the thirteen wagon makers that the elder Peter Schuttler was facing off against in 1843, the city of Chicago now had more than two hundred wagon shops. Even more jarring, thousands more outside the city and across the country were also constantly jockeying to unseat Schuttler from every sale possible. When it came to marketing, distribution, and sales, none of these challengers could be overlooked.

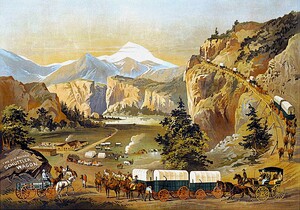

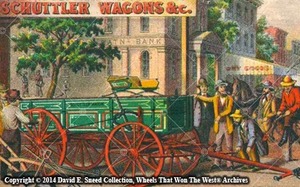

This illustration is from Schuttler's 1879 catalog.

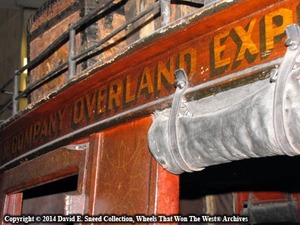

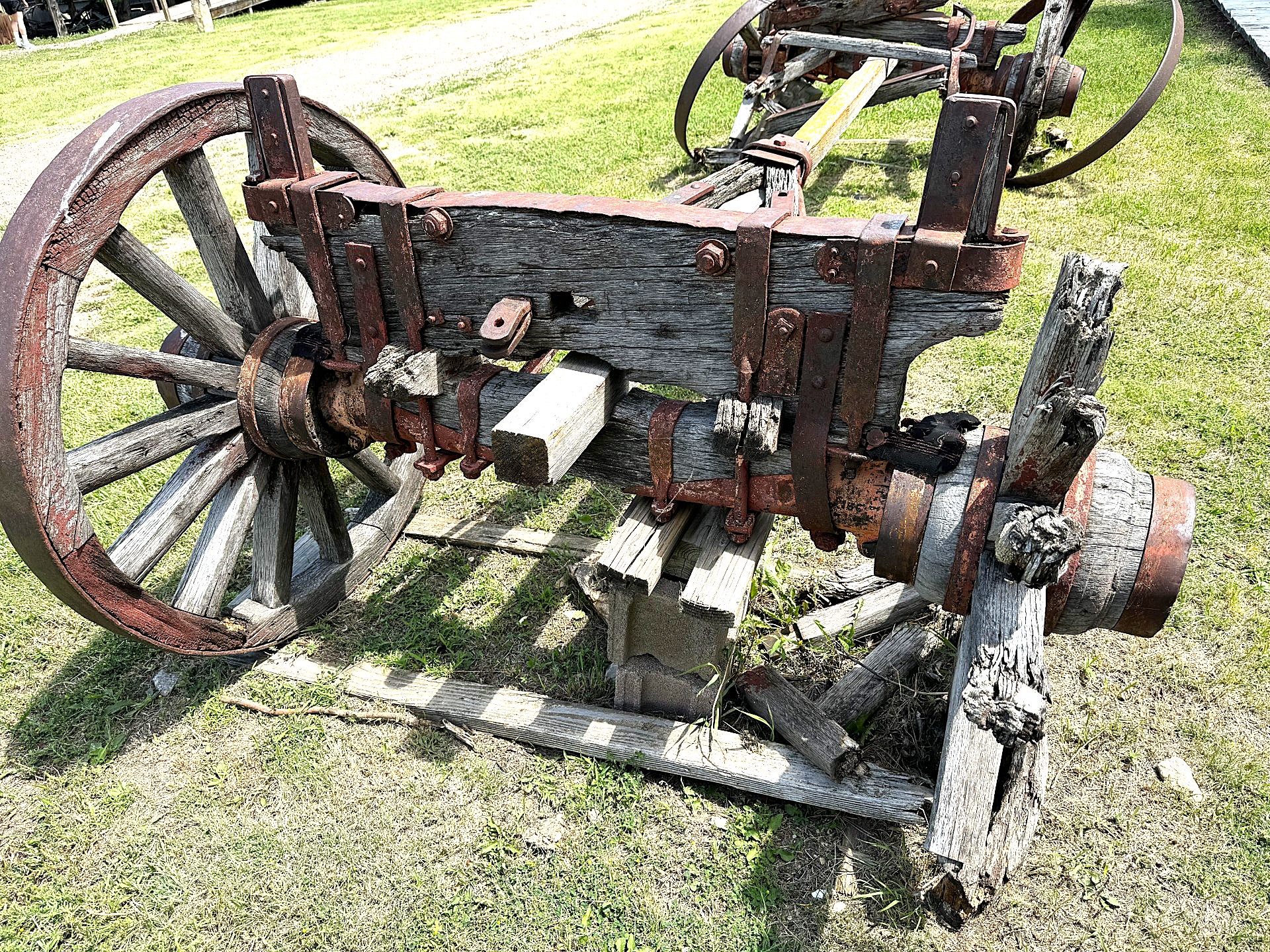

Among the vehicles in the Wheels That Won The West® collection is an 1887 Peter Schuttler wagon.

This image shows just one of the patents secured by Christoph Hotz for the Schuttler Wagon Company. This one is for a rotating or swiveling reach to help overcome the challenges of rugged terrain. The idea would be revived by another major wagon maker in the early 1900s.

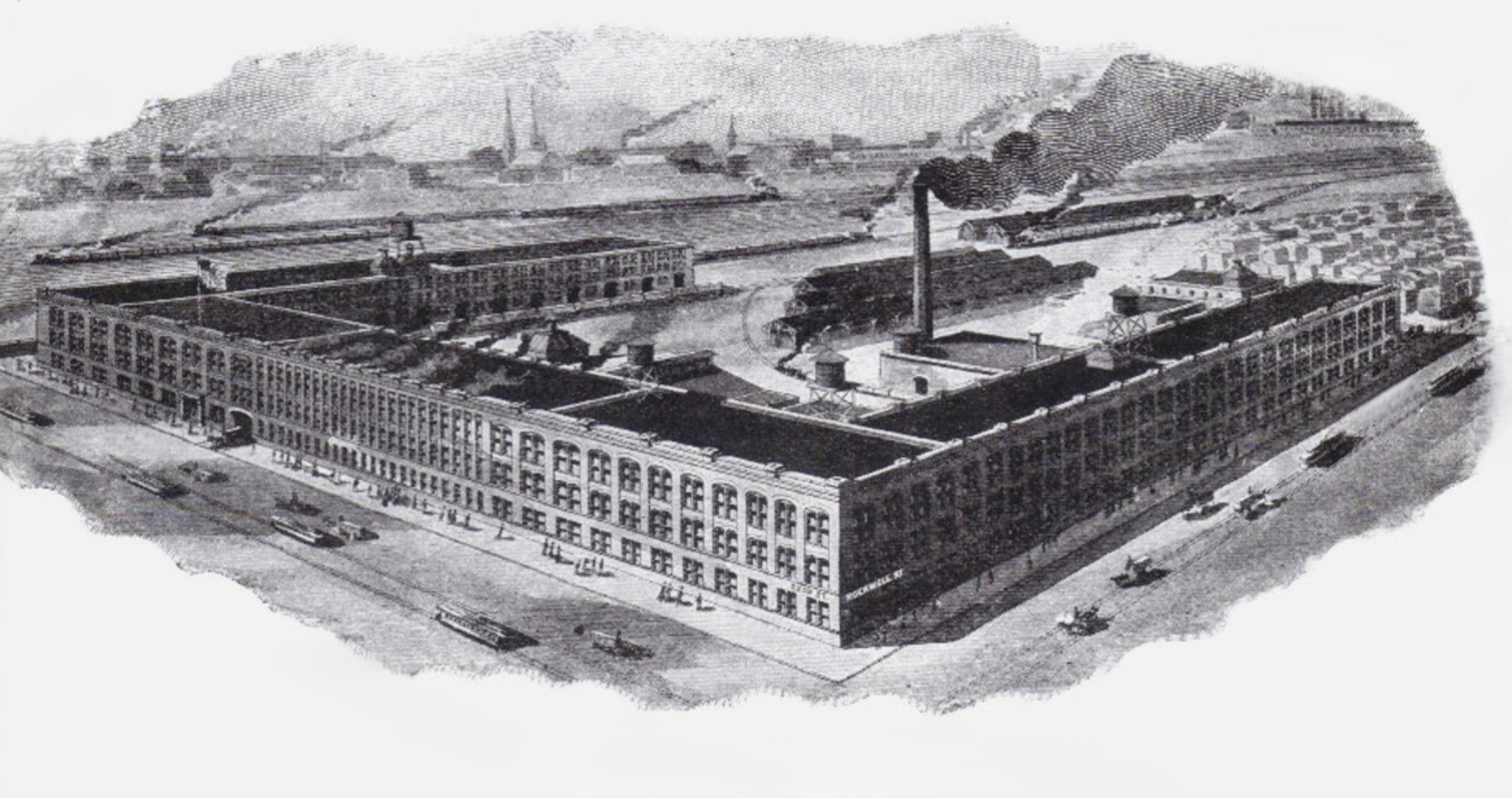

By the late 1800's, Schuttler's output was up to 12,000 wagons per year with a workforce of 400. Business was good but times were again changing and with the turn of a new century came a new competitive threat. This time, Peter Sr. and his knack for turning tragedy into triumph, was not there to save the company. As the 1900s dawned, motorized vehicles were rapidly growing in popularity. The countless patents secured by Schuttler had given the company great advantages over others. In fact, by 1904, this transportation icon was employing some six hundred folks and turning out 20,000 wagons per year†. By all accounts, the firm was formidable, but the life clock was ticking for both the company and those at the helm.

In 1904, Christoph Hotz passed away and then in September of 1906, Peter Schuttler II also died while visiting the summer home of his brother-in-law, Adophus Busch, in Germany. Schuttler was 65. His father, the founder of the wagon works had died at 52 years old in 1865. While other family members were already in leadership positions at the factory, there were numerous headwinds, not the least of which was the motor car and truck. During the teen years of the twentieth century the company appeared to prosper, at least in part, as a result of military contracts.

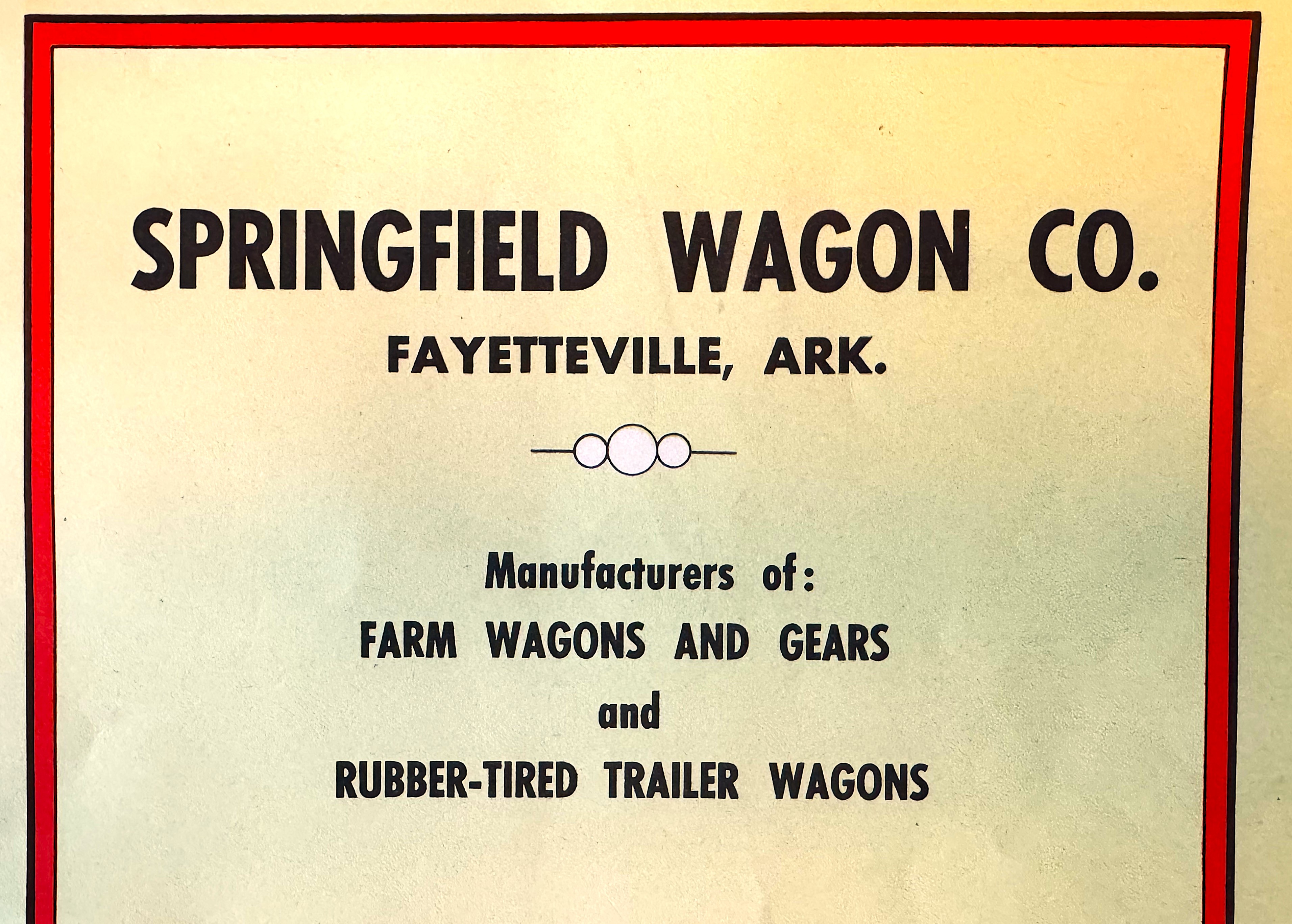

None of this provided enough momentum to combat the encounters with America's newest transportation fascination. Countless news articles touted the benefits as well as the purported detriments of what some felt was a motorized fad. The new, horseless wheels driven by gas, steam, and electricity were taking no prisoners. By the teens, there was little doubt; the handwriting was on the wall for the horse-drawn era. The connection to wood-wheeled progress was giving way to a new generation of advancements. A faint glimmer of its former glory, the Schuttler name and materials were purchased in the mid-1920s by the Springfield Wagon Company of Springfield, Missouri. Remaining open in the Springfield area until around 1941, the company was then purchased by Arkansas Senator, J. William Fulbright, and moved to Fayetteville, Arkansas. Incidentally, the remainder of the Schuttler Company in Chicago was liquidated about a year before this. The Springfield Wagon Company lasted until early 1952, being one of the last of America's wood-wheeled wagon makers. Despite the waning of its own heyday in Chicago, the Schuttler name continued to be used by Springfield throughout its last years in Arkansas.

Once acquiring the Schuttler brand, the Springfield Wagon Company made several variations of the brand.

A few more interesting notes... while the Schuttler brand always listed its establishment in Chicago as taking place in 1843, the Chicago city directory shows Schuttler as a wagonmaker on Randolph Street as early as 1839. He is not listed again until 1843, leaving us to feel he may have been 'testing the waters' prior to completely leaving Sandusky, Ohio. Also intriguing, in the mid-1850s, Schuttler is listed as both a wagon and coach maker.

Also, for those who might be curious, the elite home that Peter Schuttler Sr. built in 1865 did not survive the passage of time. A grand testimony to the power and prestige of early western vehicle makers, the Schuttler home had been filled with magnificent art treasures. Rare, original paintings and sculptures adorned the halls and spacious rooms. The bric-a-brac walls included expensive marble paneling and the hand-carved casements featured woodwork by the same Bavarian artists that had decorated the palace of King Ludwig II. Beautiful fountains and massive gardens surrounded the mansion. By the early 1900s, though, the glamour was rapidly fading. The city was changing, and the once coveted home had fallen into disrepair. Empty, it was reported by many to have been haunted. Eventually, it was sold to a boarding house keeper, then to a laundry business, and, finally, it was converted to a boarding stable. Once a home of pure pomp and splendor, nobility from around the world had dined and stayed at the Schuttler home. Now, the "House of a Thousand Candles" had fallen so far from grace that a blacksmith shop was situated in what had been the formal dining room. The intricate woodwork, so carefully installed in 1865, was marred by the bustle of wagons, horses, and workers tearing away at the interior. Ultimately, only the rare frescoes and landscapes painted on the walls and ceilings remained. In fact, period reports say that the murals were so fantastic that folks would often visit the stable just to experience what was left of the exquisite artwork. Ultimately, it was the beginning of the end and yet another reminder that man's monuments are often fleeting. The entire structure was razed in 1912. Time, it seems, has a way of erasing even the most spectacular of achievements.

A story shown in The Inter Ocean publication in 1913 highlighted the perils faced by the Schuttler family. A quick search of internet archives highlights even more tragedies suffered by the family. Image courtesy newspapers.com

Complicating the legacy of the mansion are the stories surrounding the other-worldly life some claimed it had. Almost before the paint, mortar, and last touches of wood stain had dried, reports of surreal occurrences in the massive home spread throughout Chicago faster than the fire of '71. According to numerous reports, the elder Schuttler died of blood poisoning after stepping on a protruding nail in the tower of his yet, unfinished, mansion. It was believed that on his death bed, he cursed the whole project. Still, his widow insisted on living in the home and it ultimately proved to be her undoing as well. There were so many reports of unexplained sounds, apparitions, supernatural auras, eerie shadows, and sightings that the mansion was closed and boarded up. Whispers, superstitions, and wild claims of strange experiences permeated Chicago society. Cab drivers were among the few beneficiaries as they enjoyed a great business, taking the curious past the home late at night. Even after the demolition of the mansion, the so-called Schuttler curse seemed to continue for several generations, with others in the family meeting untimely or gruesome deaths.

Throughout the brand's lifespan, Schuttler vehicles won a number of awards, including distinctions at the 1876 Centennial Exposition, the Paris Expositions of 1867 and 1878, and the Columbian Exposition in 1893.

Even with so much time having passed, the Schuttler legacy remains highly revered. Surviving wagon, carriage, and period promotional items are among the coveted finds. Historians, private collectors, horse-drawn vehicle investors, chuck wagon enthusiasts, and reenactment groups regularly scour old barns, back roads, antique auctions, and forgotten farms in search of wagons and other materials bearing the historic Schuttler badge. It's been roughly a century since the brand's last days of operation in Chicago. Still, it's easy to find folks in search of a quality Schuttler vehicle. The distinctive construction continues to set the brand apart from a world of others. Those fortunate to own a piece of this heritage can often be seen caring for the hand-built sets of wheels with the same spirit as its namesake maker. To those looking, here's a friendly word of advice. Due to the value of the best of these vehicles, it's always a good idea to review a purchase through the trained eyes of those knowledgeable in Schuttler authenticity.

Detail-driven and stylistically finished, these wheels remain a source of pride and respect... a strong reminder of the legacy of the American West and the dreams in a man's heart.

FOR FURTHER STUDY...

The internet is full of details about Peter Schuttler. Among the countless articles is one written by our good friend, author, and well-known historian, Ken Wheeling. You can find that overview of Schuttler and his wagons in the Spring 1993 issue of The Carriage Journal.

†American Machinist Jan 28, 1904

Ps 20:7