When I grew up, thephrase – “I’ll have a Coke” – was general language that could have beenreferring to about any soft drink. Similarly, as I grew up in the Ozarks,almost every wooden wagon was called a ‘Springfield’ wagon. It was such aubiquitously-applied term that it was similar to calling every facial tissue a‘Kleenex.’ Others, in different parts of the country, can likely makesimilar statements about horse-drawn vehicle brands from their own area. In fact, regional popularity of some vehicle makes was so strong that other brandsfound it difficult to effectively compete in those places. Such was oftenthe case with the Springfield brand. Even so, the early days of the firmwere not so easy. Today, numerous examples of Springfield wagons havesurvived and can be found throughout the U.S. As a nod to the roughly70-year history of the firm and in recognition of the 145th anniversary of itsfounding, we thought we’d share a bit of background on the company. Theremainder of this blog is drawn from a story I had posted on our website yearsago and subsequently shared with the American Chuck Wagon Association...

|

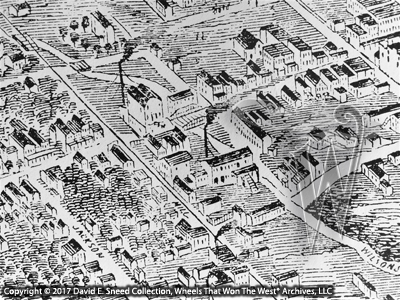

| Thisportion of an early 1870’s map of Springfield, Missouri shows the location ofthe city’s wagon factory and plow works between Mill street and Wilson’s Creek. |

A crossroads toterritories west, Springfield, Missouri was part of the historic ButterfieldOverland Mail route. During the Civil War, the area was the scene ofseveral heavy battlefield engagements. The location also lays claim to whatwas easily one of the few true, one-on-one, fast-draw gunfights in the entire OldWest. It took place in 1865 between Wild Bill Hickok and Davis (Little Dave) Tutt from Arkansas. Into this heritage-rich western backdrop, in 1872, the Springfield WagonCompany hung out its shingle and announced its entrance into the wagon buildingindustry. Surrounded by quality hardwood forests, the region was aready-made market for quality farm, freight, ranch, log, and businesswagons.

From the start, thegoing was anything but easy. Floods, fires, economic depressions, bankingscares, and distribution challenges were regular obstacles. True to thearea’s convention, though, Springfield was as stubborn as a Missouri muleand never gave up. Their gradual successes caught the serious attentionof numerous competitors, including the Studebaker Brothers of South Bend,Indiana. In spite of price wars and public challenges by the largermanufacturers bent on running Springfield out of business, thecompany struggled on. In 1883, the firm was hit especially hard as it suffered the ravagesof a massive fire. Through the sobering reality of charred remains, the company picked up the pieces and carried on. At the end of the day, the investors were in too deep for failure to be an option. Even so, this would not be the last of the brand's hardships. Legal battles for technology and construction features flaredup from time to time and after the turn of the 20th centurycontinuous pressure from the motorized farm and transportation industry beganto take the heaviest toll.

|

| Likemany other major brands, Springfield often emblazoned its name on the endgates, axles, sideboards, spring seats, and even some hardware. |

By the mid 1930’s,during the twilight of its most successful years, the Springfield Wagon Companyhad outlasted most all of its major competitors while also becoming the soleremaining source for replacement parts to many of the most recognized names inthe history of western transportation. Legendary icons like PeterSchuttler, Fish Bros., Bain, Pekin, Smith, and Ebbert all eventually founda home inside the powerful and resilient Springfield brand. Ina bid to gain even more business and market share, Springfield branded wagons,boxes, and running gears under a variety of trade names including Springfield,Ozark, Missouri Mule, Ironmaster, Jack Rabbit, Acorn, and even Bain andSchuttler. Often the only difference between the vehicles was the paintedname. As a result, and in spite of the fact that a Springfield wagon hasnumerous unique construction features, if the paint has disappeared on a latermodel Springfield farm wagon, it’s possible that what might be thought of as aSpringfield today, might actually have been originally built and branded as a“Schuttler.”

As with many other earlyvehicle brands, the design makeup of a Springfield wagon did change over theyears. One of the places where some of these evolutionary adjustments canbe seen is in the design of the standards (bolster stakes). While most ofthe earlier Springfield farm wagons used rings in the standards, later models usedmultiple variations of metal bands serving as pocket stakes in thestandards.

How many Springfield wagonshave survived? It’s hard to say. But, after building hundreds ofthousands of both wood-wheeled and (later) rubber-tired wagons during its nearseventy-year history, those that do remain are certainly part of an eliteminority. Some were even part of America’s war efforts. Truehistorical icons, these rare wheels stand as a lasting tribute to a time whensteady resolve and patient persistence paved the way to the survival of thefittest.

Additional informationon Springfield wagons can be found in the book, “The Old Reliable, The Historyof the Springfield Wagon Company,” by Steven Stepp. This book as well asa reproduction copy of the company’s 1915 catalog are also available through our website.

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC