From devastating wrecks of stagecoaches and tall-sided freighters to harrowing reminders of weather, sickness, and troubles with terrain, we have some amazing records of early American travel in our Wheels That WonThe West® archives. I was looking through some of our images this past weekend and found myself marveling, yet again, at the sheer tenacity of what it took to trek through the Old West.

Far from the frustrating ruts, potholes, and narrow, fractured shoulders in the highway leading to my twenty-first century home, frontier transportation required a whole other level of boldness and commitment. Sitting high, atop a mud wagon or freighter, looking down was not for the faint of heart, even if there were no cliffside drop-offs or washed-out ravines to deal with. Lonely stretches with little to no help in sight, top heavy vehicles, unpredictable teams, and volatile weather were standard fare.

As I stared at one image, I was overwhelmed with the immense size of the roadbuilding project shown in it. Here was a single lane ledge barely beaten out of the side of a rock wall and situated halfway up a near impenetrable section of the Rocky Mountains. This was just one part of the road. It seemed like an unstable and unpredictable pathway more suited for mountain goats than wooden wheels and shod hooves. The vehicle on it looked like a tiny, die cast toy sitting on the side of Mount Rushmore. On the one hand, it was a beautiful scene, capturing the majesty and magnitude of nature. On the other, it was a fully fearsome and frightening reminder of the risks involved in what today is considered a relatively simple task. Sheer drops with loose rock made up the outside shelf of the pathway. Makeshift bridges hastily formed from tree trunks spanned gaps where the rock ledge had given way during heavy slides and torrential rain or snow runoff. Massive erosion loomed above the trail with unrooted trees hanging precariously, waiting for the right moment to release a surprise onto those below. There was no protection, no on-call roadside assistance, no guardrails, cell phones, or helicopter evacuation teams ready to help those in need. It was truly a time of testing for men, mettle, and machines.

The earliest days of travel had few "rules of the road." Hames bells and turn-outs allowing other vehicles to pass on single lanes were among the first, rudimentary road safety features in mountainous areas. As time passed, there was a bit more structure applied but it was still an entirely different world from the engineered road angles, shoulders, water drainage designs, and safety signage of today.

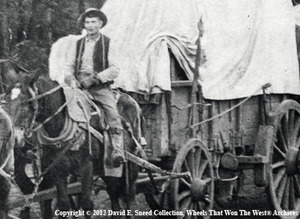

Tall-sided western freighters came in different shapes and sizes. Most major wagon makers marketed and sold these types of heavy rigs into the early part of the twentieth century. Image Courtesy Wheels That Won The West ® Archives.

With that in mind, I thought I'd share some background to horse-drawn freighting as it was viewed at the turn of the twentieth century. Below are a few outtakes from the Yearbook of the United States Department of Agriculture, 1900. The chapter on 'Mountain Roads' is especially interesting since it highlights some of the challenges faced by western freighters as they carried everything necessary for life during the expansion of the West. Basically, if it was eaten, used, mined, or worn, these wheels hauled it throughout some of the most rugged and isolated areas imaginable. The author of the article, James Abbott, wrote the review to inform others of the needs for better road infrastructure in the West. He begins by saying...

"... The freighter with his mule teams furnishes transportation, and for his use are built the first mountain roads. The motto is 'Get there and get there quickly.' The first consideration seems to be a route over which vehicles on four wheels can travel without tipping over. It is often so steep in places that wagons can only be pulled up with blocks and tackle and descend with wheels rough locked and dragging a heavy log behind."

Next, Abbott begins discussing the importance of the proper grade for roads in mountainous terrain...

"... For freight traffic, the maximum grade admissible is 12 per cent. Four animals, together with the one or two wagons used on a mountain road, are all that one driver can safely and properly handle on steep grades. When he uses two wagons, lead and trail, at every stop ascending he must hold both wagons by the brakes on the lead." (DS NOTE - there were also instances of freighters dragging chock blocks that would position themselves behind the rear wheel(s) as a stop when the wagon ceased moving forward - Doug Hansen, Hansen Wheel & Wagon Shop, has an excellent example on the tall-sided Studebaker freighter in his collection).

Doug Hansen next to his restored, tall-sided Studebaker freight wagon.

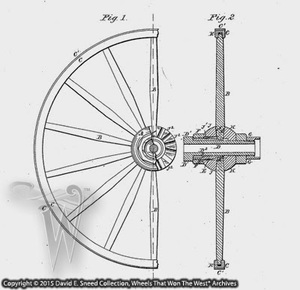

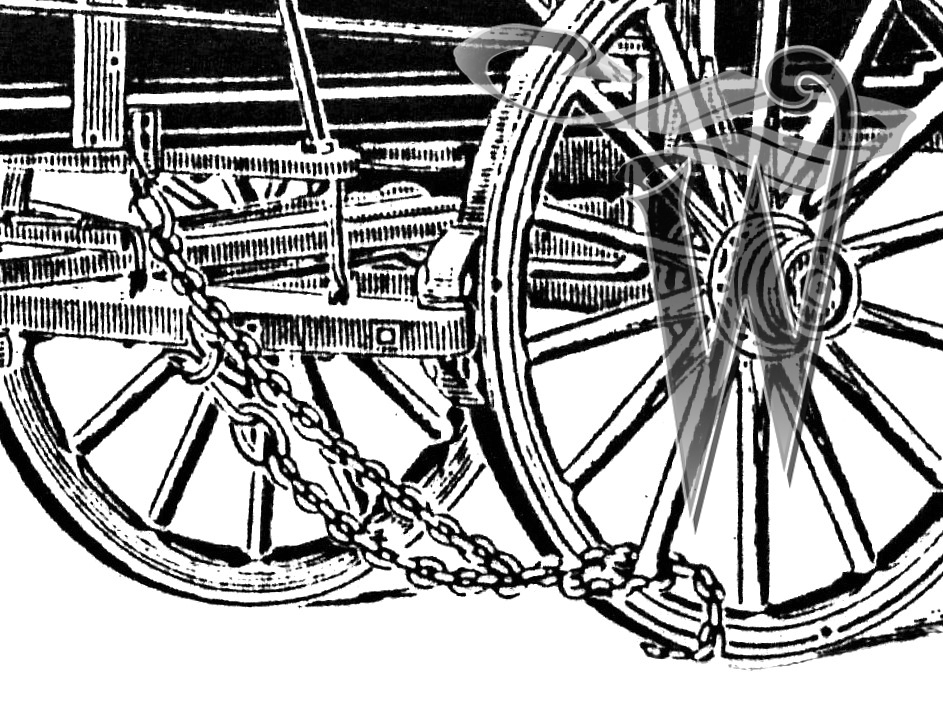

"In descending with heavy loads,excepting when the roads are icy, he must control his wagons with brakes on both - the lead by the lever beside his seat, the trail by a strap leading to the brake lever. When the road is icy, he must control the descent by rough locking one or more of his rear wheels. To rough lock, he must attach some rough device, like a piece of chain or short steel runner, grooved on the upper side to fit the tire and with projecting prongs on the lower, to the felly of a rear wheel, just in front of the point where it rests upon the ground. A chain attached firmly to the center of the forward axle is then tightly fastened to this rough lock. Thus secured, as the wagon descends the hill, the wheel remains rigid and the rough lock plows into the surface of the road."

This image shows an original freight-wagon drag shoe hanging from the Studebaker wagon. There were many styles and sizes of this piece of equipment and this hardware was used in mountainous regions all over the United States.

All four (4) of the items above are referred to as Drag Shoes. Used to help slow and control descents in rugged, mountainous terrain, these iron accessories were crucial tools for early wagon freighters. Image Copyright © David E. Sneed, All Rights Reserved

This extremely rare cut is from our Wheels That Won The West® Archives. All rights for its use are reserved. It shows a lock chain doing double duty as a rough lock. Primary source imagery such as this helps provide a world of information as to how things were done during wagon freighting days.

This 1900 article is relatively detailed, so we won't have the time or space to get into all of its points but here are a few additional take-aways from the piece...

> Always locate roads on slopes facing south and east in preference to slopes facing north and west. These areas allow the sun to help with snow melt and road drying.

> A side hill tends to offer a better location for a road than a creek bottom. It's always better drained and generally has a more solid foundation.

> Bridges are costly to build and expensive to maintain. Road builders were encouraged to minimize the number of river crossings in their designs.

> While a level road was encouraged to have a center crown to drain water, a road on the mountainside needs a higher outside and lower inside edge to drain into a ditch. This helps prevent the water from spilling over and washing away the outside bank.

> The recommended safe width of a 'single track' (1-lane) road was twelve feet with ten and, in some cases, eight feet being acceptable. (NOTE - these wagons were typically over six feet in total width. Combined with multiple teams of horses or mules, an eight-foot roadbed width seems to be an invitation for trouble and, no doubt, where some issues did arise!)

> The article states that the "proper width for double track (2-lane roads) and heavy teams is 16 feet, while it is possible for them to pass with extra caution on a 14-foot track on a straight road." (WOW! That seems tight!)

> Double track turnouts (pullovers) should never be shorter than seventy-five feet in length.

While this overview was written in 1900, it provides some important insights into western freighting as well as a reminder that 'knowing the road' was just as important (if not infinitely more) back then than it is today. It also points to the value of accessories like drag shoes, lock chains, and rough locks as well as properly maintained vehicles, draft animals, and harness. Today, period rough locks, lock chains, and drag shoes can still be found but they're highly sought after as collectible reminders of the early days of freighting.

Have a good week!

Psalm 20:7