Over the decades, I’ve shared a lot of details related to western wagons and stagecoaches. Most of that material has been focused on brand histories, individual vehicle traits, collector tips, barn finds, and similar vehicle-centric information. While all of that is crucial to understanding these aged machines, there’s another narrative I’d like to share... that is, every nineteenth-century vehicle was a witness to a world that’s gone.

Even so, many of those wheels were active participants inside some of America’s most amazing history. I imagine those moments would have kept today’s social media abuzz with instant posts and video feeds showing some of the wildest rides on wooden wheels. Can you imagine traveling on a sidling hill perched atop a coach or freighter, ten feet above the ground, watching the earth race by; all of it happening at breakneck speed behind a six-horse run-away...or an infusion of adrenaline trying to outrun desperate road agents... or what about watching as an iron Rough Lock was wrapped around a seven-foot tall wheel and the massive, tall-sided freighter edged over a steep precipice, tipping side to side while sliding unnervingly down a ravine-shaped trail... or maybe even a heavy emigrant wagon lowered over a cliff to gain an advantage in a river crossing or make up time to avoid snow in a pass. To quote an old phrase, there were endless ‘hills to climb.’ With that in mind, we’re embarking on a new series within this blog. It’s called, “Seeing The Elephant.” In these special posts, we’ll share tales of the wheeled West from a different perspective. These are stories that are seldom heard but were closely tied to the transports that moved America west.

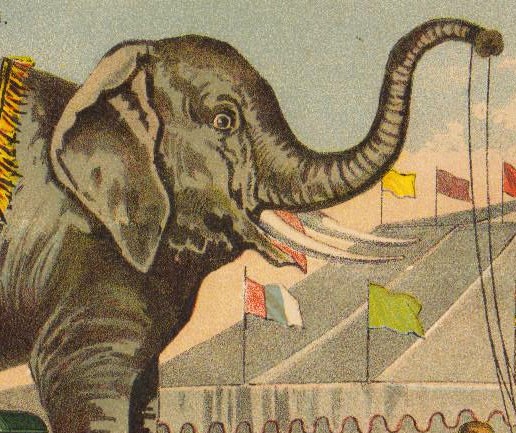

For some, the ‘elephant’ title might seem strange, at least until you know where the phrase comes from. In 1796, when the first live elephant was seen in the U.S., it created quite a stir. As a result, it was common to hear refrains like, “I’ve seen the elephant” or “I want to see the elephant.” In today’s language, it would be similar to hearing someone say, “Been there, done that” or “That’s on my bucket list.” During the 1800’s – and particularly during America’s westward migration – the phrase captured a sense of gaining or having the worldly maturity of someone that’s ‘been around’ so-to-speak.

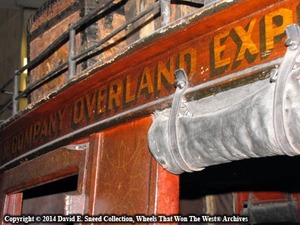

There are a lot of transportation-related ‘Elephants’ tied to western history. Most are rarely shared or even known. Those unique tales and experiences are what this particular segment is about. To that point, there may be no stronger and more independent personality in the Old West than the freighters that hauled goods in and out of some of the most challenging and dangerous places on the North American continent. If it was dug, worn, used, or eaten, these folks were the ones that hauled a good part of it overland. They often lived isolated lives while making civilization possible for others. The vehicles and animals they drove were equally extraordinary.

The term, ‘western freight wagon’, can be a bit confusing as it can apply to a number of different styles of vehicles including tall-sided freighters, Mountain wagons, Rack bed wagons, and even heavier Farm wagons, as well as a wealth of different Stake Bed and Dray designs.

In today’s post, the wagon described was likely a rack bed, heavy farm, or possibly a Mountain wagon; although, the set of wheels could have been a taller freighter. Ultimately, the cargo didn’t weight a lot but it was definitely different than the norm. The incidents mentioned below coincided with the discovery of gold in the Bannack, Montana region during the early 1860’s.

As mines were developed and the fever for precious metals grew, so did the number of people in the mining camps. With large quantities of people in small areas, health issues were bound to follow. Among the concerns was the rapid increase in rats, mice, and other disease-carrying vermin. Droppings, saliva, and urine from these undesirable critters filled the camps, making them ripe for sickness and death to come knocking.

As the story goes in an 1894 retelling of Montana history, two men came up with an ingenious way to make money while helping solve the pest problems in the mines and camps. Below is a journal entry highlighting a trip in the spring of 1863...

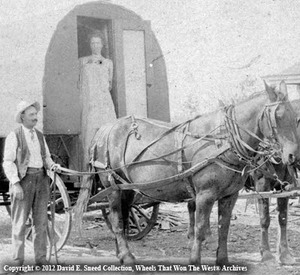

And oh, the rats, mice, vermin of all conceivable sorts in the mines! This spring – 1863 – two of my former schoolmates who had been with me in Idaho, John Thompson and Jeff Blevins, set out from Eugene, Oregon, with a wagon load of cats. Their cage was capsized inTemhi (Lemhi) Pass at great loss of cats; and packers and teamsters passing that way for a long time told wild stories of weird Indian cries at night in that region; but a woman went out one day with her children and quite a string of cats followed her home and the strange, weird screams were heard no more.Thompson and Blevins told me they sold their cats as fast as they could hand them out, at from $10 to $75 each, according to sex, color, condition, and former degree of servitude.

– from the Journal of My Brother, JohnD. Miller

Either someone got spring and autumn confused or there were two deliveries of these formidable felines from Oregon because there is a second story also included (this one is attributed to the fall of 1863 instead of the spring time mentioned above)...

In the autumn of 1863 Thompson and Blevins came into the mines of Idaho from Eugene, Oregon, with a wagon-load of cats. A small consignment of this remarkable merchandise was forwarded to Bannack, Montana, and sold ‘like hotcakes’ at prices ranging from one to four ounces, according to ‘sex, age, and condition of servitude.’ It was told on good authority that in a cabin where a cat was kept, the men, on rising from the table, no longer turned down their tin plates in preparation for the next meal. But do not misunderstand me. The cat was there to catch mice, not to polish up the new tin plates with a little red napkin.

Talk about a couple of entrepreneurs thinking way out of the box!! Thompson and Blevins were onto something. The only problem might have been that the cats likely reproduced faster than they could truck new batches into the remote mining communities. As a result, the experiences in 1863 seem to be the last mentions of the feline freighting ventures. Even so, these kinds of risks and endeavors highlight the realities of life in the West during the Civil War. Freighting covered a multitude of needs, even ones with teeth and a tail!

So, the next time you’re in a museum or a destination featuring a rare western freighter, think about all the places it’s likely been and what possible ‘freight’ it may have carried. From raw ore and food stuffs to clothing, hardware, machinery and more, these wheels braved all types of wrecks, war, weather, terrain, outlaws, and unknowns. They were essential parts of early western transportation and their arrival in a community was greatly anticipated; even if it meant they only made it by a whisker – or, in somecases, several whiskers! 😊