If you’ve spent much time on a farm or ranch, you’ve probably built your share of fence. Likewise, over the years, I’ve not only strung a lot of wire but been completely drained while digging post holes. Some were easy but, since I live in the Ozarks, most have been challenging. Roots, rocks, hard ground, and melting heat are abundant in these historic hills. Hence, an equal amount of muscle, sweat, and determination are essential to tackle the jobs. It doesn’t hurt to have an iron pry bar and even a jackhammer handy. In many ways,the process is a perfect metaphor for what’s required to help solve some of the greatest mysteries in America’s first transportation industry.

Incredibly complex, the study of this trade is one of the most extensive and involved investigations a person can tackle. Among the many reasons it’s so taxing are both the depth and breadth of the craft as well as the expanse of the associated professions. Likewise, the length of time since this was a common part of everyday life adds another dimension of unfamiliar terrain.

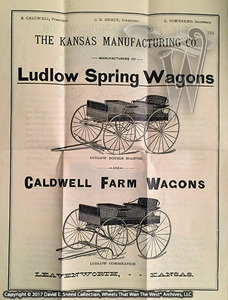

Regular horse-drawn vehicle use covered a period of roughly 200 years in U.S. history. During that span, there were tens of thousands of KNOWN vehicle businesses. That number doesn’t include the vast support industries that were making supplies, parts, tools, harness, etc. Confounding it further, this is a world with its own language, methods, and designs – some of which actually crossed over into the age of automobiles.

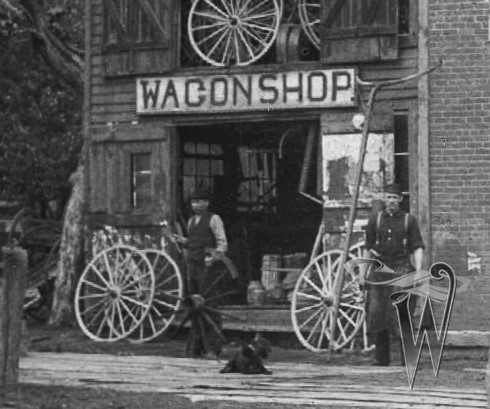

The Wheels That Won The West® Archives include the names and locations of almost 40,000 horse-drawn vehicle makers and repairers. Additionally, years ago we uncovered an 1887 quote from Clement Studebaker (the same Studebaker company that built cars & trucks) who shared his belief there were at least 80,000 vehicle builders in the U.S. during that time. The sheer size of this industry is a huge obstacle for historians and researchers.While some have attempted to use census data for guidance through the maze of makers, that information is, at best, limited. At worst, it’s misleading. There are a number of reasons why. First of all, with records only updated every ten years, early census data simply didn’t have the visibility to capture all of the makers that existed during a particular timeframe. Many builders came and went before and after censuses were taken. Other firms merged or were difficult to find. Second, census records can have a hard time reconciling builders who were also involved in other activities. For instance, the majority of America’s first vehicle makers were not massive or exclusive operations such as that of the Studebaker Brothers. Instead, the chief business of a good number of wagon makers was blacksmithing and horseshoeing. Others were primarily focused on their hardware store or lumber yard, funeral services, livery operation, furniture making, freighting operations, or – well, you get the picture. Far from putting all their eggs in one basket, there was a lot going on with many builders. To that point, if a hardware store also made and sold a few wagons (and a number of them did), how did the census account for that diversity and was that full mix of products always reported by the business? In other words, did the hardware company label itself as a furniture maker, seller of hardware, a funeral parlor, lumber yard, general store, or something else entirely? There was a considerable amount of crossover in goods and services provided by some of these makers. As a result, research focused exclusively on census records runs a risk of not fully capturing all services provided by a business. Third, as with any attempt to gather comprehensive data, a census can be incomplete, no matter the intentions. Paper records can be lost, others may not be fully filled out, and some may never have been completed.

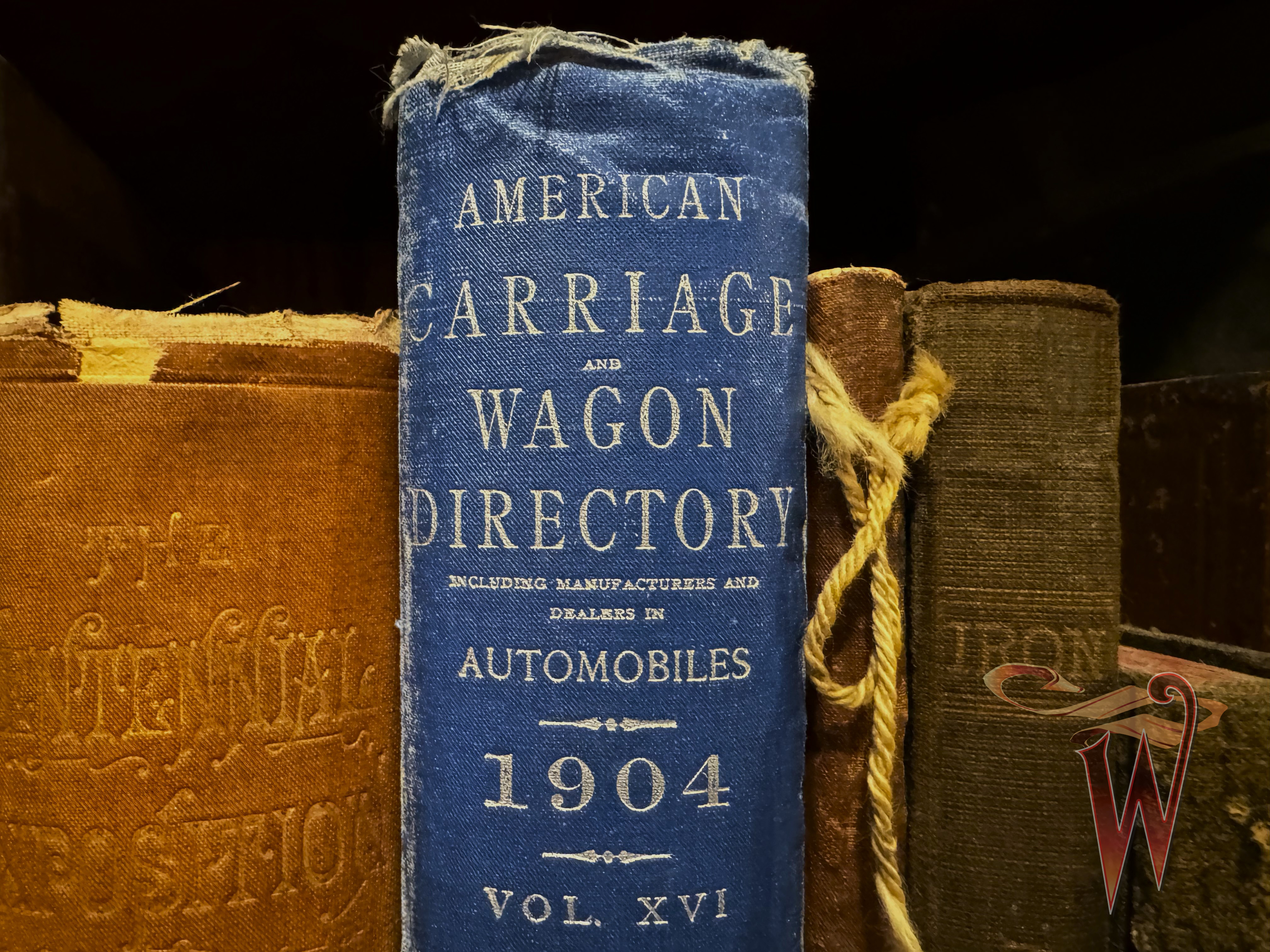

To make authoritative sense of this wood-wheeled hodge-podge, we must look at how the industry presented itself back in the day.This includes reviewing directories published for the transportation industry during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In contrast to the broad approach of a census attempting to capture and label every possible business, these industry reports are targeted records fixed on recording a more complete image of America’s early vehicle works. Inside those, and other surviving records, is a much different story than that provided by the census information, alone. For instance, early 1900’s census numbers show the wagon and carriage industry to number around 5,000 makers. During the same timeframe, the creators of Price & Lee directories show the vehicle maker industry to be made up of over 38,000 builders and repairers. Clearly, there’s a huge difference between the counts and, based on eyewitness summations like that of Clement Studebaker, it’s obvious that more makers existed in the U.S. than were reported in the decade intervals of the census. The main point of this illustration is there’s a lot to consider when looking at the numbers. Part of the challenges in the examples I just outlined may lie in how the term ‘maker’ is defined. But, even if a business builds one vehicle per year or even less often, are they still considered a maker? Likewise, while some information can be difficult to find, other details may seem straightforward while masking a deeper issue.

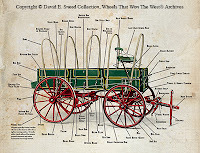

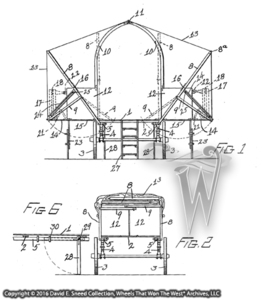

Ultimately, the roads we travel in researching the vehicles, advancements, and industry often take us into other areas as well. To gain amore thorough comprehension of why things were done when, where, and how, we’re often forced into deeper, more forensic examinations. Studies involving math, science, art, history, metallurgy, blacksmithing, drop forging, casting, dendrology, lumber, paint, varnish, tools, patents, processes, and more are all part of the extensive knowledge base that’s associated with wagon making. These areas also aid in the understanding of specific vehicle brands, dates, uses, processes, and design evolution, itself. The entire subject is far from simple and definitely not a quick study.

As part of the humility-shaped curriculum, diligentr esearchers have learned to shy away from descriptive absolutes like ‘always’ and ‘never.’ All-inclusive words like those have a way of setting us up for failure as they’re often impossible to objectively support. As an example, I once heard someone say that the legendary Peter Schuttler brand ‘always’ built every farm wagon the same way with the same colors and design. It’s not a true statement and that point can be proven in multiple ways. To get to the truth on any brand, though, we have to continually dig for reliable, primary source answers. Opinions, personal experience, and educated guesses are not necessarily the same as comprehensive facts. To the contrary, following objective processes requires us to eliminate assumptions and personal bias while viewing every set of wheels within the timeframe it was created.

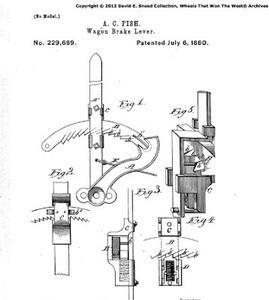

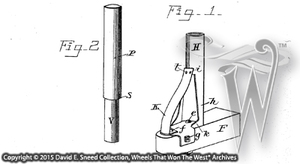

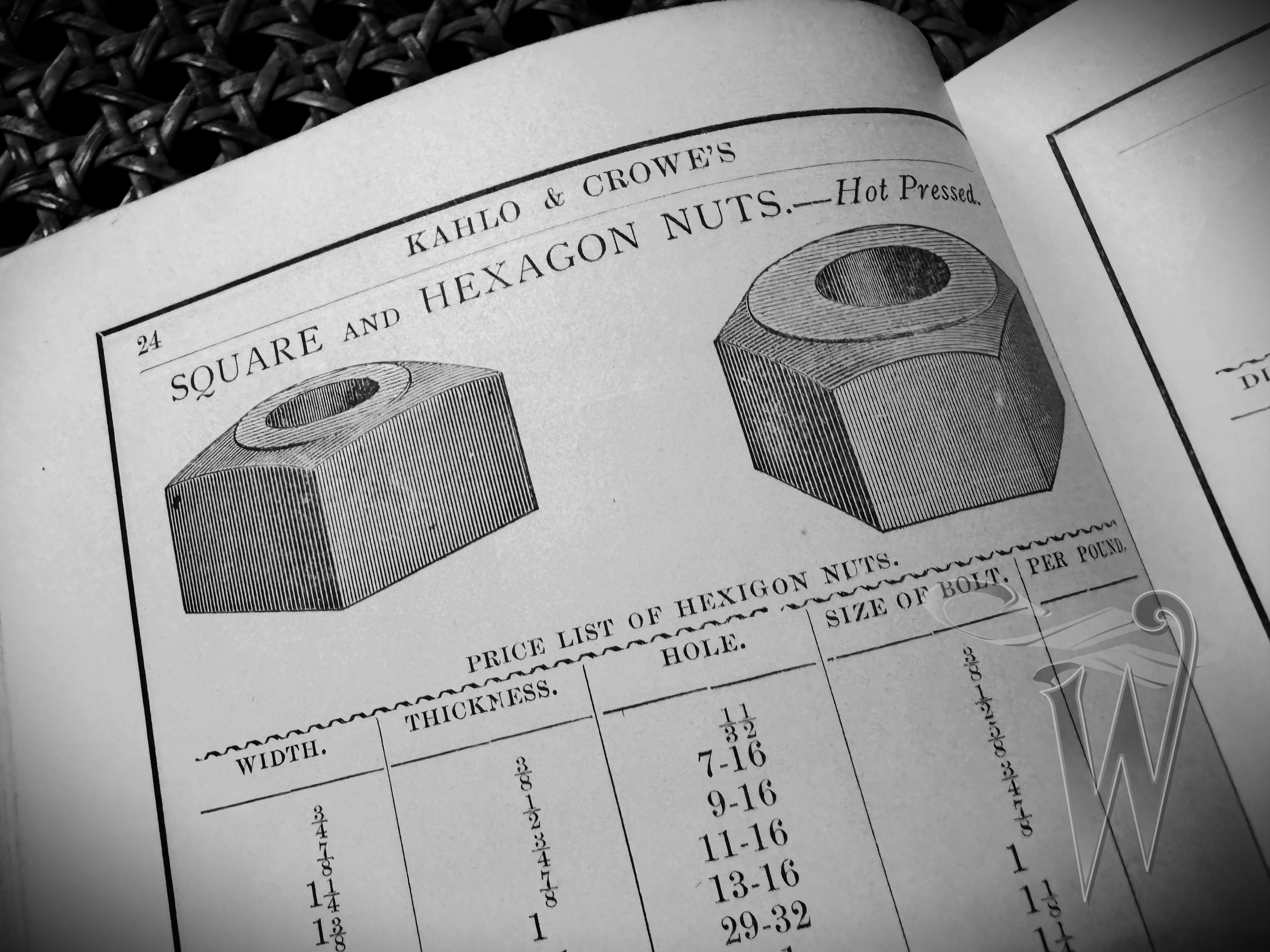

Using the right lens to view these early machines is literally the difference between correct conclusions and jumping to conclusions. A more direct point is that we can’t look at these old vehicles exclusively through 21st century eyes. What do I mean by that? I mean these pieces were built during a different time, place, and conditions. So, the who, what, when, where, why, and how’s don’t always match up with the conditioned thought processes of today. An example of what I’m sharing is an assumption that, due to a perceived limitation of technological ability, some have said that hex head nuts and bolts weren’t available throughout the vast majority of the 1800’s. This is clearly an incorrect supposition based on insufficient research. How do we know this? Hang on and I’ll share just a few of the ways.

Time and again I’ve heard things like, “Wagon makers in business during the cattle drive era didn’t use hex head nuts and bolts because those nuts and bolt heads didn’t exist then.” This is a point that isn’t literally true but we need to dig a little to understand just exactly where the facts do land. In reality, the truth is somewhere in the middle. In other words, a statement saying that something didn’t happen might be both true and false. About now, you’re saying, “Okay, David – how is something right and wrong at the same time?” Here’s how... this particular ‘hex nut’ comment is wrong as to whether the nut design appeared on wagons by or before the 1870’s. It’s also wrong to more broadly assume that the hex designs weren’t even around at that time. A simple look at period hardware catalogs shows the error of that assumption. On the other hand, the same statement is partially correct in the sense that many notable wagon makers were not using hex nuts/bolt heads during the cattle drive era (1860s, 70s,& 80s). So, in this instance, it’s important to KNOW what a specific maker did or didn’t do since the technology for hex nuts/bolts was definitely in use during that time period. Some might ask, “Why is this even a concern?” For many, it’s probably not. But for collectors and history buffs, knowing who did and didn’t do something is what authenticity is all about.

We can even take this study beyond most of the surviving, nineteenth-century hardware catalogs and maker literature. How? Well, using the Peter Schuttler brand as another example here, we know that the company was indeed using hex head nuts/bolts at least as early as 1856. We know this due to the discovery of a Schuttler running gear uncovered in 1988. The gear was found on the Steamboat Arabia which sank in the Missouri river in 1856. It’s a great story and even more interesting vehicle to see. If you get a chance to visit the Steamboat Arabia Museum in Kansas City, you’re bound to be impressed by all the materials uncovered on the boat.

Image courtesy of the Steamboat Arabia Museum. All Rights Reserved.

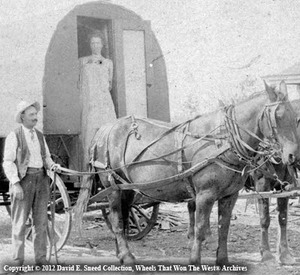

Complicating other elements of early horse-drawn vehicle research, there are common terms like Conestoga, Concord, Road wagon, Mountain wagon, sway bar, decalcomania, point band, reach box, wagon lock, and many others that, while a fluent part of conversation back in the day, can often be confusing, misapplied, or altogether unknown today.

Along the same lines of previously-mentioned assumptions and conjecture, dates of manufacture can be thrown around like pancakes on a griddle, giving no regard for supportable truth or the realization that, other than God, everything else has a beginning. While some beginnings can be tough to pinpoint, others are clear and documented. Finding that introduction point gives us an important baseline when examining a vehicle from a supposed timeframe. Every part of a period wagon will have these telltale signs and understanding what each part of the construction is saying is essential to properly interpreting a timeframe of manufacture.

When it comes to modern day assessments of these designs, sometimes we’re so used to being spoon fed information through the internet that it’s tempting to accept whatever the search results APPEAR to turn up – written or visual. Before passing along unsupported information found on the internet, ask yourself if the details are based on sustainable, primary source backgrounds? In other words, is that repainted and re-logoed wagon really an “1880’s such-and-such brand” or might it be a different brand from the twentieth century? Is the date so obvious that the evidence could withstand objective, legal scrutiny? Sometimes it can but, oftentimes, the only ‘evidence’ is casual hearsay or bold guesses completely devoid of truth.

Likewise, it’s easy to depend far too much on the way these wheels are portrayed in western movies, social media posts, special events, and even some museums. Why would I say that? I’ve seen numerous dates of wagons that were clearly inaccurate. Again, every part of the wagon has something to say about its maker and the time period it was built. Some of the more commonly misapplied timeframes can be found in popular movies and western programs. I’ve seen it over and over in programs supposedly representing everything from the late 1700’s to the early 1880’s eras. In these cases, using a vehicle that was clearly built AFTER the turn of the twentieth century is a tough pill to swallow, especially if authenticity is important. For some, that might sound like a small detail but what if those same movie cowboys, ranchers, farmers, soldiers, or pioneers were fitted with a gun that didn’t exist until fifty years later than the time period represented? How would the authenticity levels be looked upon in that case? Would it be legitimate to show a 1910 automobile in an 1870 cattle drive? Ridiculous, right? It’s the same situation with western vehicles. These pieces are not all the same. The different eras are packed with differences. Most of the major wagon brands – and even smaller builders – evolved over time. It’s the same process of continuous improvement that’s regularly seen in the auto industry today. Change came to these old wheels and, through our research and vast collection of primary source materials, it’s not uncommon to be able to pinpoint an era, if not a very close creation date for wagons.

Regrettably, when something is old and worn, it can be tempting to accept provenance declarations with no sustainable proofs. A sustainable proof is one that will hold up to objective, fact-based scrutiny. It’s a level of authenticity that doesn’t rely on rumor or coffee shop boastings. After all, if truth is only what we ‘say’ it is, with no objective primary source support, then everything can be truth and there’s no difference between one vehicle and another.

Clearly, there are obvious design shifts that the wagon industry as a whole tended to make during different eras. I’ve repeatedly shown these transitions in many of my presentations and writings. As stated earlier, it’s the kind of differentiation we also see in the automobile industry. For example, today’s pickup trucks are consistently built with power windows, power steering, and power brakes. When my dad was growing up, those features were largely unheard of. Later, the same technologies were optional and, eventually, they were standardized. In the same way, almost no part of the wagon is immune from shifts in technology. Again, it’s one of the ways we’re often able to pin down manufacturing timeframes while reinforcing authenticity in a particular vehicle or brand.

Time and again, it’s too easy to look at a wood-wheeled wagon and assign design explanations that label all wagons as if each is mirror of the other – they’re not. Similarly, it’s too short-sighted to assume things must have been done a particular way if we haven’t taken into account the history of the industry, the brand, or the times.

In the upcoming, second part of this article, I’ll cover more of the challenges, assumptions, and misunderstandings that permeate the study of early western vehicles. Along the way, I’m hopeful the information helps grow your own appreciation for this amazing but complicated subject.

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC