Any student of history will readily admit that the subject has a way of repeating itself. Good ideas, in particular, will often resurface from generation to generation. It’s a propensity that’s easy to see in a number of areas. In the first volume of our western vehicle book, Borrowed Time, we share details related to an 1875 patent for twin axle steering. The idea was used in a number of areas within the horse-drawn transportation industry and, more recently, was part of a 4-wheel steering concept for Chevy trucks. A variation of multi-axle and wheel steering is also used in competitive vehicle events like rock climbing and monster truck shows.

Even a brief perusal of early wagon companies will show that some ideas between brands were duplicated in these vehicles. It’s one more reason we always strongly advise against relying on a single feature when attempting to identify any particular vintage wagon maker. We’ve covered some of this before and will discuss even more in an upcoming post.

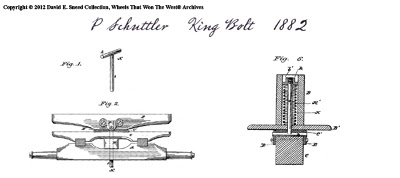

When it comes to competitive and innovative wagon makers, the Peter Schuttler Company from Chicago is one of the most legendary and distinctive brands. Throughout their history, the firm secured a number of patents on early vehicle designs. One patent they received in 1882 dealt with a unique configuration for a king bolt. Connecting the rocking bolster, sand board, reach and axle together, this entire configuration received a tremendous amount of stress. More than simple one-dimensional pressure, the connection to the rocking bolster also racked the pin in numerous directions and angles. It’s a construction feature that continually placed high demands on the king bolt. Unfortunately, the pin did not always fare well under the strain. Hence, the patented T-handle-shaped king bolt that allowed the forward bolster to float more freely, somewhat independent the bolt.

Now, fast forward an entire half century to 1932 and note the similarity in a pertinent element of one of Springfield Wagon Company’s patents. Even though the patents are separated by 50 years, there are clear similarities in the king bolt function and design. It’s one more example of how good ideas tend to re-surface as well as an admonition to use great caution when looking at single elements to identify wagons that have lost their maker marks.