Several years ago, we updated our website and transferred all of the 'Wheels' blogs and articles to one location. Unfortunately, during the process, a few of the older stories were missed and haven't been included with the rest. I recently came across one of these earlier pieces and thought it would be good to re-post it on the site. Hope you enjoy it...

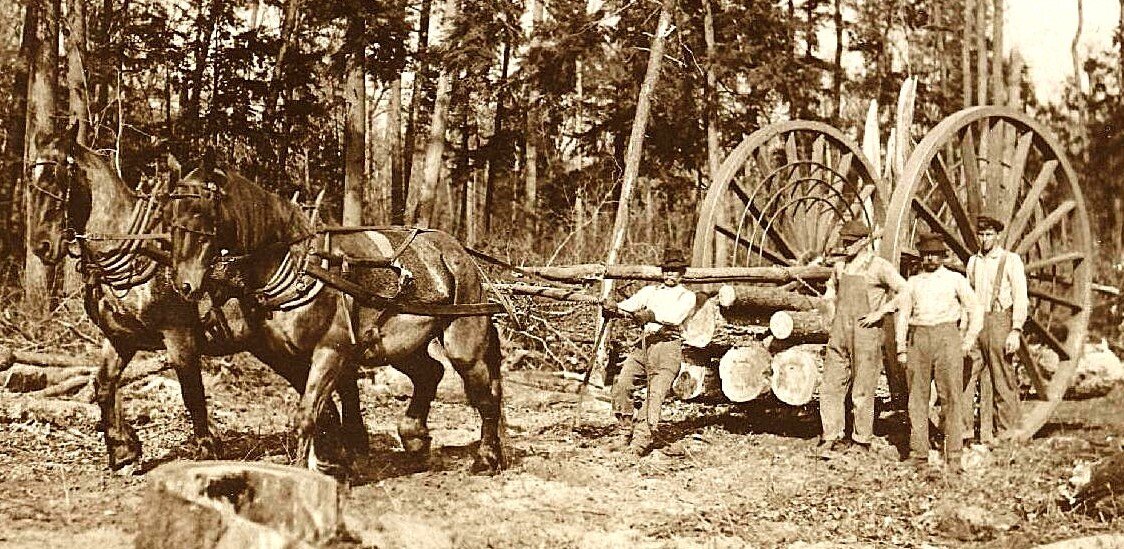

Ever found yourself yearning for a job in the great outdoors? Spend a couple weeks swinging a splitting maul and stacking firewood or maybe take an extended 'vacation' to cut some logs for extra money and you'll likely be proud to get back to your regular job - whatever it is. Excursions like those are just small reminders of what was required to work with timber in the 1800s. While the tasks are still time-consuming, gone are the days when getting timber out of the woods was such a physically arduous task. In stark contrast to the challenges faced by nineteenth and early twentieth century loggers, today's modern skidders, hydraulic operated lifts, tractor-trailer rigs and other machinery have increased efficiencies and significantly enhanced safety. Over the centuries, one thing that hasn't changed is the constant demand for the wood resource. According to multiple sources, our (U.S.) per capita consumption of wood continues to rise. So significant is wood today that some stats show its use exceeds the combined weight of all steel, aluminum, plastics, and concrete used. Replenishing this appetite for wood is reflected in the fact that tree planting in the U.S. is estimated to total more than 2.5 million acres each year.

Original High Wheel logging cart image Courtesy of the Wheels That Won The West® Archives.

Similarly, in the late 1800s, wood was a vital and profitable commodity. But, unlike the twenty-first century, earlier days had other dilemmas. Beyond accessing and cutting down the huge virgin timber, just moving the wood from the remote forest floors could be especially tough. Rugged terrain coupled with long distances to mills, waterways and rails severely hampered progress. Ultimately, it was just the kind of burden that has always inspired folks to rise to the challenge with determined innovation.

A portion of a rare letterhead from S.C. Overpack dating to the 1890s. It is part of our extensive freighting collection housed in the Wheels That Won The West® Archives.

So it was that in 1875 Silas Overpack of Manistee, Michigan crafted his first set of "Michigan Logging Wheels" or "High Wheels" as they came to be known. As the history is told, a decade or so after the end of

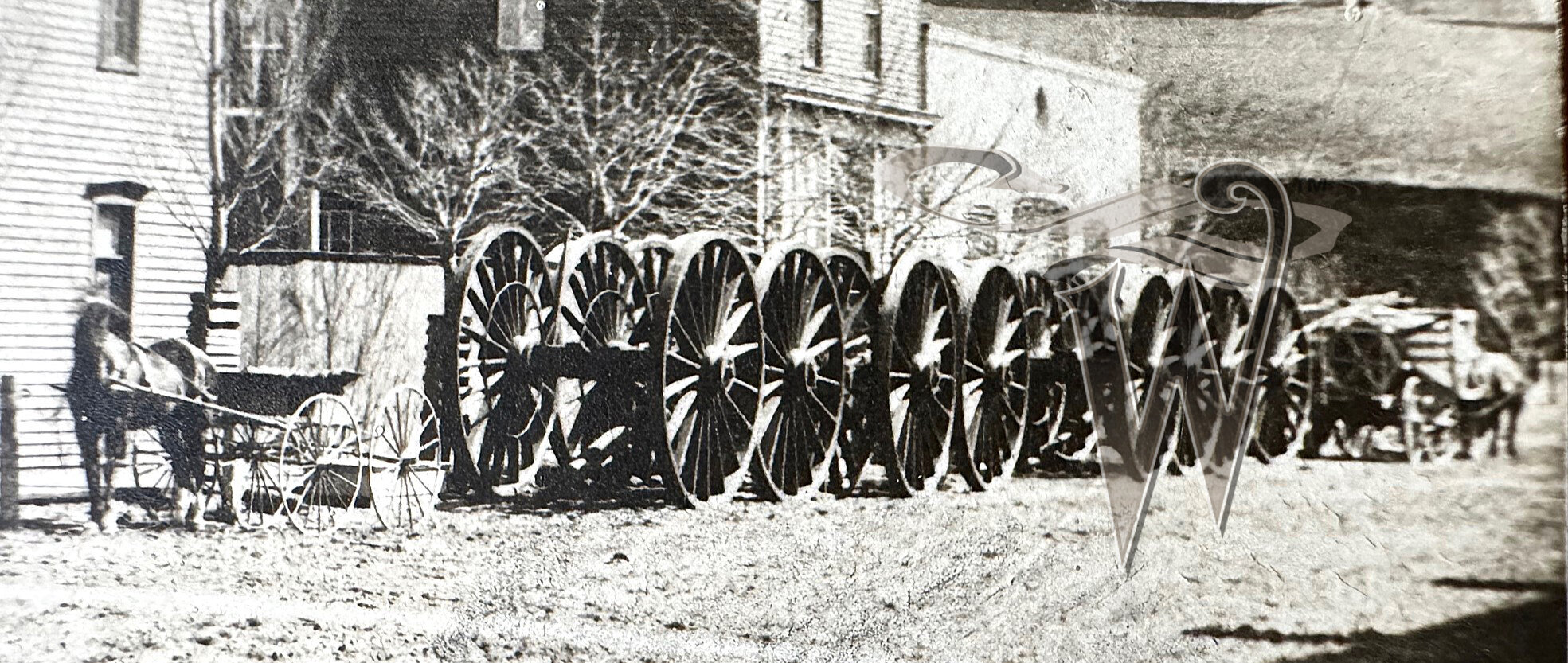

A number of High Wheel logging carts sitting outside the S.C. Overpack factory in Manistee, Michigan. Image courtesy of the Wheels That Won The West® Archives.

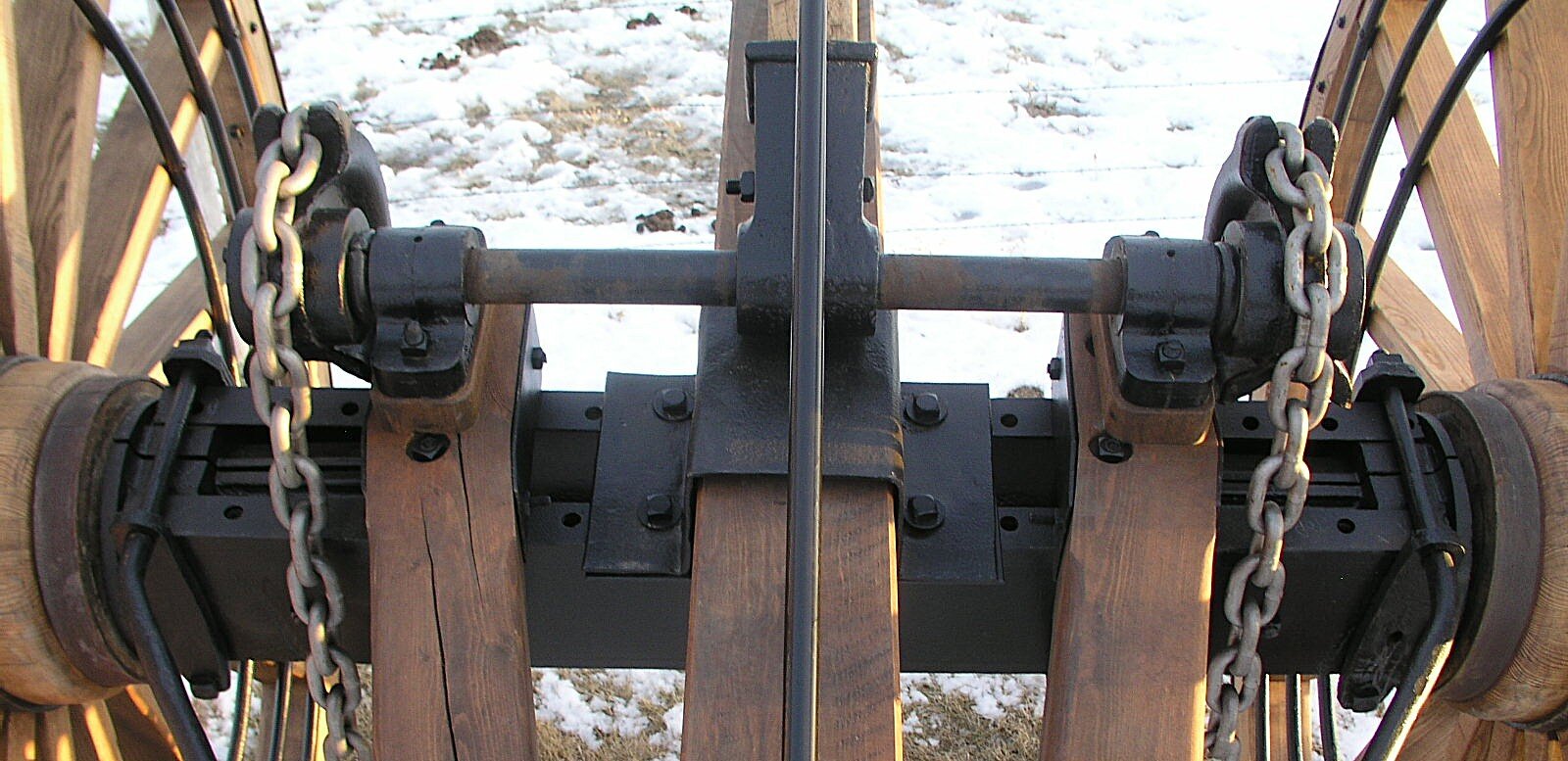

Original Overpack specs in the Wheels That Won The West® Archives indicate that these machines were capable of carrying logs from twelve to one hundred feet in length. Hubs were made from Wisconsin white oak, the eighteen spokes came from rock elm, felloes were white ash, tongues were fashioned from ironwood poles, and axletrees were hard maple. In the mid-1890s, Overpack was making nine, nine-and-one-half, and ten-foot-tall wheels for these vehicles. When describing the operation of the massive cart, Overpack explained it like this, "The logs are placed in position - as many as can be placed so that the wheels can pass over them - and when the axle is over the center of the logs, stop, raise the tongue by taking hold of the lever which is on top of the axletree, until the tongue stands in a perpendicular position, then pass the swing chain under the logs and make fast to the short chain which is hung on the lug pin on the axletree. Before raising the tongue, fasten a rope or small chain to the end of tongue long enough to reach the ground when the tongue is up: then hitch the team to the chain or rope and pull the tongue down and make it fast to the logs. The axletree is so constructed that when the tongue is lowered it will raise the load to its proper place."

Image Courtesy Wiki Commons

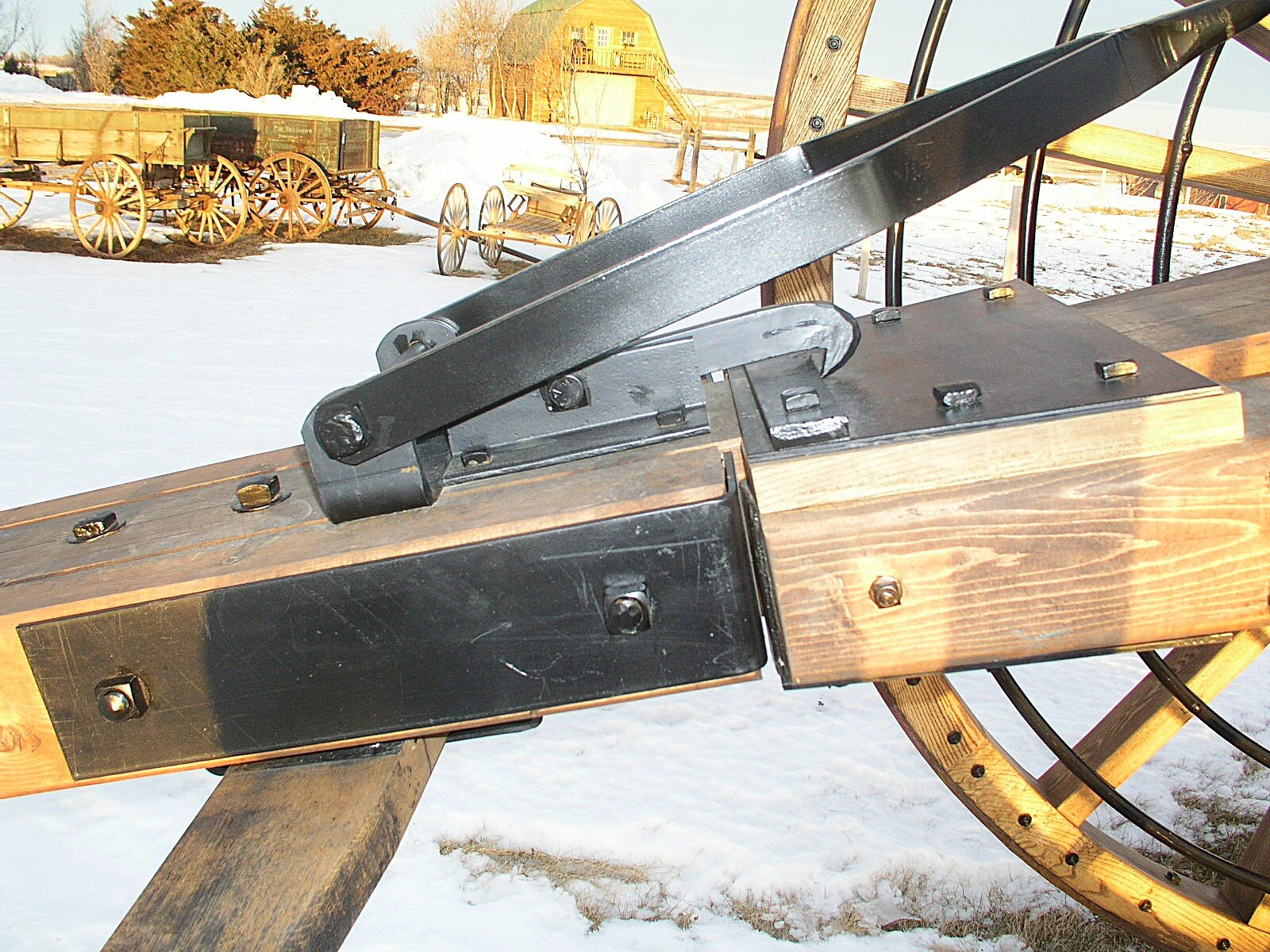

As valuable as they were to timber companies, there was one problem with the big-wheeled machines... initially, these giants had no brakes. In relatively flat areas of the country, this wasn't as much of an issue. But in the steep timber country of northern California, Oregon and Washington, it was a serious safety concern. The owner of Redding Iron Works, John Webb Sr., came up with an ingenious solution. He developed a "slip-tongue" that allowed the cantilevered Jacob Staff (rod/lever system) to help lower the logs on downhill grades thus serving as a drag to slow the entire rig. The High Wheels worked to lift the logs when the team of horses pulled on the tongue. As the horses moved forward, the tongue slid forward and also pulled the rod and lever, rotating the chain cams and raising the logs. Going downhill, the cart would slide forward on the tongue, automatically lowering the logs back to the ground. It was a very effective design that saved the lives of horses and workers while greatly increasing productivity.

In addition to Overpack, a number of other manufacturers created High Wheel logging carts including the Gestring Wagon Company in St. Louis, Wilson-Childs from Philadelphia, and Hobson & Company with offices in New York and factory in Tatamy, PA.

Some time ago, a rare and dilapidated set of these wheels was given to Rogan Coombs of Fortuna, California. Sharing a long history with the timber industry, Coombs immediately made plans to add the wheels to a working museum he and a few friends had planned to open. According to Coombs, these High Wheels were made at the Redding Iron Works and were originally sold to the Weed Lumber Company for use in the big pine country of the Northwest. From the timber they hauled to the history they made, everything about the wheels had an imposing air; the colossal size of the hubs, the diameter of the massive wheels and the questions the piece, itself, brought to mind. It all combined to put the wheels of Comb's own mind in motion. Ultimately, this scarce piece of timber history was enough to convince him to gather all the parts and investigate the possibilities of having the Big Wheels restored to their original glory.

Relying on the western vehicle expertise at Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop, Coombs had the decayed remains of his giant wood-wheeled skeleton shipped to Letcher, South Dakota. Once there, it fell to Hansen's staff to not only restore the wheels, but help ensure their historical accuracy. Scouring vintage articles, photos and other primary source archives, Hansen is a perfectionist when it comes to matching history and nineteenth century craftsmanship. He describes it as being a little like an archaeologist looking for clues.

With eighteen oversized spokes, each wheel weighs in at 850 pounds! Image Courtesy of Doug Hansen, Hansen Wheel & Wagon Shop.

These ten-foot-tall logging wheels instantly dwarf most most modern vehicles.

Adding the six-inch steel tire required plenty of assistance.

Hansen's research and documentation reinforce the fact that, in the 1800s, the remote reaches of America's virgin forests were no place for the weak or ill-equipped. Consequently, the original specs for the logging wheels read like something out of the legendary tales of Paul Bunyan. Clearly, their looming size is indicative of a vehicle built for serious ventures. The hubs measure a whopping eighteen inches in diameter and extend the better part of two feet in length. Eighteen spokes span a width of six inches each and the felloes have an equally impressive set of dimensions at five and a half inches wide by four inches deep. Broad steel tires measure a full six inches across and the wheels themselves weigh a bone-crushing 850 pounds each. Combined with a slip pole stretching some thirty feet in length, the inside circumference of the ten-foot-high wheels are equipped with three iron bumper rings for extra protection when carrying logs. Elsewhere, the axles were constructed of a wooden clouted stub spindle with linch pins.

According to Hansen, "This was a challenging but truly enjoyable project. Even though most of the wood was deteriorated beyond further use, we were able to create patterns from much of what existed. A large percentage of the hand-forged metalwork was still intact and our historical research enabled us to pinpoint missing parts, restoring them to period authenticity."

A few detail images as well as the finished product. Courtesy of Doug Hansen, Hansen Wheel & Wagon Shop.

After a year in Hansen's shops, today the High Wheels again stand as a remarkable example of American ingenuity and achievement. Weighing close to 3,500 pounds, this giant set of wheels sold for $350 a century ago. Today, it's valued at roughly one hundred times that much. Rogan Coombs and his friends have already used the High Wheels in local California demonstrations and while the huge cart is still adept at moving timber, its impressive size is equally successful in stopping traffic.

Big Wheels... High Wheels... Michigan Logging Wheels... Logging Carts... whatever you call them, they still inspire, reminding us of a time when it took strong horses, determined men, and the largest of wheels to make a living felling timber, load it on a cart, and then get it all Out Of The Woods.

Big jobs are nothing new for Hansen's crew as they have also done conservatory work on several of Ketchum, Idaho's surviving freight wagons. As seen in the photo above, this massive, 1880s freighter literally dwarfs a reproduction, full-size Concord Coach. This and five other freight wagons are part of regular tributes to Ketchum, Idaho's early mining history. Image Courtesy of Doug Hansen.