Throughout the majority of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, St. Louis, Missouri was a significant force in American transportation. Home to hundreds of horse-drawn wagon, stage, carriage, omnibus, and buggy makers as well as an equally impressive group of vehicle dealers and material suppliers, the area outfitted countless farmers, freighters, emigrants, businesses, ranchers, and military exploits. It's a story and reputation unparalleled by any other city.

this week, we'll dig up a few more details related to wagon makers from the Gateway to the West. To get the most out of any research, though, we often have to not only dig deep but look close. After all, it's easy to miss maker clues. To that point and, as I've shared before...

Old wagons talk to me. I know that might sound a bit strange, but early wheels do have a language and typically have lot to say. One of the best ways to hear what is being said is to focus on where the vehicle was made. For serious collectors, it's one piece of information that can hold a wealth of details related to brand identity, design, construction style, purpose, features, rarity, and even competition in the market.

Location. Location. Location.

While most early wagon builders were small shops serving limited regions, many prominent makers capitalized on location. An area with easy access to navigable rivers, rails, and roads was almost always a favorite spot. Chicago, for instance, was home to notable brands like Peter Schuttler and Weber. South Bend, Indiana claimed Studebaker, Birdsell, and Coquillard. Racine, Wisconsin, boasted the large factories of the Mitchell, Racine, and Fish Brothers brands.

St. Louis' position on the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers made it a natural crossroads for westward traffic and commerce. In fact, so many business opportunities existed there that, by the 1880s, the city was home to about 140 wagon and carriage builders, far more than any other city west of the Mississippi at that time. By the turn of the 20th century, directories show St. Louis with nearly 200 horse-drawn vehicle builders. The industry was so significant that some suppliers sent the majority of their production to the city. Many contend that St. Louis was home to more nationally-recognized wagon companies than any other U.S. city.

Among those Mound City makers, several notable brands played significant roles in U.S. history. From immigrant travel to freighters, cattle drives, and military campaigns, St. Louis wagons were well represented throughout the country. Many of those builders are still highly regarded by historians, enthusiasts, and collectors. Among the standouts in St. Louis are the names of Joseph Murphy, Louis Espenschied, and Henry Luedinghaus.

J. Murphy & Sons

Established in 1825, Joseph Murphy's shop was one of the oldest successful wagon manufacturers in St. Louis. Likewise, Murphy is arguably the most discussed and least known of any major U.S. wagon maker. Even though Murphy and his wagons are regularly referenced by collectors and academics, many questions remain about his company. In fact, of the 200,000 wagons purported to have been built by Murphy, not one has been conclusively identified as a survivor today.

From the few historical accounts and company records that do exist, it is known that Murphy wagons achieved a significant reputation within the freighting community. In fact, according to the recollections of D.P. Rolfe, a freighter in the 1860s, "The freight wagons used were the Murphy and Espenschied, made in St. Louis, and the Studebaker, made at South Bend, Indiana... More of the Murphy make were used than either the Studebaker or Espenschied..."

Murphy is often referenced today in connection to a customs duty imposed on American freighters traveling to Santa Fe. In 1839, the governor of New Mexico imposed a $500 tax (over $17,000 in 2025) on EACH freight wagon traveling into the area. The toll caused serious financial heartburn to the freighters, but Murphy is said to have come to the rescue, building giant wagons capable of hauling enough goods to offset the tax. It's a story that sounds plausible, but no period accounts supporting it have been found.

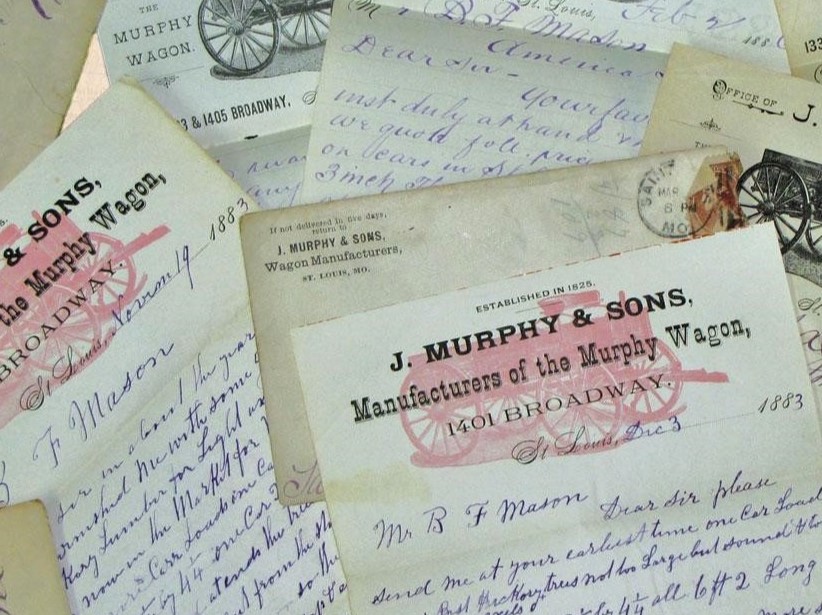

Several years ago, I was fortunate to discover thirteen letters sent from J. Murphy & Sons to an Illinois wood mill. Four of the letters were written by the elder craftsman himself. The correspondence detailed the wood he was seeking and information on when and how it should be cut. It's believed that these pieces are the last surviving business correspondence from Joseph Murphy. Appropriately, every faded stroke of the pen confirms Murphy's legacy as both an expert in wood and an extreme stickler for quality.

By 1888, Mr. Murphy had relinquished control of his company to his sons. The firm continued to build wagons until just after the turn of the 20th century, making it very possible that some of these vehicles are just waiting to be discovered. It would certainly be an intriguing opportunity to confirm any Murphy wagon.

Espenschied Wagon Co.

Of all the early St. Louis-built wagons, there were likely none that gave Joseph Murphy greater competition than those made by Louis Espenschied. In the city directory of 1859, sixty-five wagon makers were listed but only two paid for advertising space... Murphy and Espenschied. Established in 1843, Espenschied Wagon Co. is eternally tied to the growth and history of America's movement west. From immigrant travel to the needs of the gold fields, freighters, and military, Espenschied wagons carried a large reputation.

As part of that leadership, Louis Espenschied headed a group of four wagon makers that solicited the U.S. Army in 1861, offering to build as many wagons as were needed by Union forces. Espenschied proposed construction of six-mule wagons with 2-1/2-inch iron axles. The wagons would carry 5,000 to 6,000 pounds; the same designs were said to have been used by freighters traveling to New Mexico and Utah. Espenschied priced them at $125 each and pledged them to be better than Army regulation wagons. The proposal noted that the companies' "many years' experience in making Wagons for the Great Plains" enabled the four to craft the very best vehicles.

The proposal was immediately accepted. An order for two hundred was placed within 10 days of the July 6 proposal. No other bidding took place as the needs of the Civil War were urgent and the reputations of Espenschied, Jacob Kern, Jacob Scheer, and John Cook were unquestioned. The wagons were promptly built. By December of the same year, Espenschied made another proposal to the Army for 1,000 more wagons at the same price.

Like other makers of his time, Espenschied's devotion to his craft showed in design innovations. In 1878, he was granted a patent for a built-in grease reservoir on the axle skein. That feature allowed the wheel to go longer periods with less lubrication. In an 1882 company profile, Espenschied is also given credit for an even earlier major advancement in wagon design: the thimble skein. It was an innovation adopted by virtually all wagon makers.

This old newspaper ad is from 1927 and long after the original Espenschied-branded wagons were built by Louis Espenschied.

Espenschied died in 1887, leaving an estate valued at almost $500,000 (almost $17,000,000 as of this writing). Soon after, his firm merged with that of Henry Luedinghaus, forming the Luedinghaus-Espenschied Wagon Co. Today, there are still a few existing Luedinghaus-Espenschied wagons, but an Espenschied dating to the original firm has yet to be identified.

Luedinghaus Wagon Co.

Henry Luedinghaus started his own wagon manufactory in 1859. In the early days, Henry was in a partnership with fellow wagon maker, Casper Gestring. In 1865, he joined forces with his in-laws. The firm then became known as Luedinghaus & Arensmann until at least 1868.

The Luedinghaus Wagon Company was located across the street from his old partner, Casper Gestring and the Gestring Wagon Company. In fact, the areas occupied by Luedinghaus, Gestring, Espenschied, and Weber-Damme were all within blocks of each other.

Henry Luedinghaus' company distinguished itself by making high-quality farm, freight, business, log, and lumber wagons. By 1878, Luedinghaus was not only building to order but also maintained an inventory of wagons that could be purchased on-site. At about the same time, the company began bidding on government contracts. An 1880 Luedinghaus proposal of $61.50 per wagon was handily beaten by the firm of Austin, Tomlinson & Webster. The winning bid from this Jackson, Mich., company was $57. The price advantage was hard for traditional makers to overcome: They were built by state prisoners who were paid little for their labor.

In spite of the challenges of competing on a national scale, Luedinghaus continued to grow. The company motto was, "The wagon will speak for itself." It's no wonder the vehicles were popular. Luedinghaus claimed to be the first to offer the exceptional strength and reliability of Bois d' Arc wheels. Some may know this wood as 'Osage Orange' or 'Hedge Apple.' All wood in the wagons was said to have been thoroughly seasoned for two years before use and paint was painstakingly hand-brushed, not dipped. Dipping was a faster process but some found the resulting adhesion inferior.

In 1889, Henry Luedinghaus purchased the Espenschied Wagon Company and renamed the new company as the Luedinghaus-Espenschied Manufacturing Company.

At the 1904 World's Fair, Luedinghaus displayed a pyramid of eleven wagons. The massive exhibition dominated the competition and generated vast publicity. The spectacle was a physical duplication of the company's official trademark and tagline that proclaimed, "We Tower Above All."

For a brief time in the 1920s and early '30s, Luedinghaus built auto bodies, trailers, and trucks. It was a valiant attempt to change with the times, but the challenges of the Great Depression were too much to withstand. The firm closed its doors in 1934.

Week to week, we're sharing details of countless nineteenth and early twentieth-century transportation titans. These highlights are just a portion of our focus with the Wheels That Won The West® Archives. For over thirty years, we've been fortunate to help uncover and preserve vast sums of primary source materials, giving us greater insights into the numerous brands with ties to the American West.

Ps. 20:7