Seldom does a week go by that I don't receive a number of questions related to early wagons. It's a subject of constant curiosity and fascinating connections to America's movement west. This week, we'll provide the next dozen answers from the original list of questions we shared on April 12th. If you have a particular question related to an early wagon brand or the industry as a whole, drop us an email. We'd enjoy hearing from you...

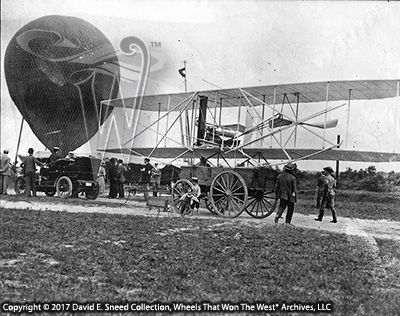

13) Nineteenth century military forces were sometimes accompanied by 'Balloon wagons.'

Very true. The term, 'Balloon wagon,' refers to a four-wheeled escort-style wagon (some with undercut wheels) equipped to carry the necessary fittings and gear, including thousands of feet of wire rope, necessary for military balloon operations. Also accompanying the balloon wagons were Cylinder wagons holding the gases for the balloons. As early as America's Civil War and for more than a half century afterward, tethered balloons were raised with personnel on board to help provide aerial reconnaissance of the enemy and surrounding terrain. From design to operation, it's a subject that warrants greater attention than what we have time for in this brief blog.

14) The Springfield wagon company only used one style of seat - a lazy back.

While many are familiar with the 'taller' lazy back seat (with backrest) that is fairly common on a Springfield wagon, the firm actually made several different styles without a raised backrest.

15) To keep a skein from having too much longitudinal wear, there should never be any slack when the wheel is rocked side to side.

This one is false as the wheel is supposed to move roughly a quarter inch on the longitudinal axis of the skein. It's a design feature that helps distribute the axle grease. I wrote a blog back in September of 2013 that included period documentation highlighting the fact that some longitudinal movement isn't just normal - it's necessary.

16) Tongue supports or springs (for wagons) were in use as early as the 1850's.

Absolutely true. Our files include multiple patents for tongue springs and various other methods of supporting a wagon tongue. The earliest patent for a tongue spring that we're aware of dates to 1857. The purpose for a tongue spring was to take the pressure and weight of the wagon tongue off of the draft animals while still allowing hinged movement of the drop tongue.

17) While a wagon is being drawn forward, the pressure on the reach pin makes it impossible for it to work itself out of the reach plate and coupling pole.

Anyone who's ever driven much or looked closely at a reach pin knows this to be a false statement. Most reach pins have a slot for a cotter-type key, nail, wire, or some other 'keeper' in the hole on one end. The reason? As a wagon travels, rough terrain and jarring motions of the vehicle can easily dislodge an unsecured pin. The results can be unsavory to say the least. Some wagon builders, like the Stoughton Wagon Company, even used a reach pin that screwed in, making it especially tough to loosen up and fall out.

|

| Many Stoughton brand wagons utilized a reach plate with a threaded pin and tension plate. The design was originally created by T.G. Mandt. |

18) The running gears of Bain brand wagons were always painted orange.

Orange was the predominant color of most Bain wagon running gears. With that said, yellow was also used in a number of instances. In fact, in November of 2014, we highlighted a very nice Bain rack bed wagon located in the Angels Camp Museum in California. We share these types of small details to help increase awareness and limit erroneous stereotypes that can often be applied to these early wheels.

19) Wagons with Bois d'arc (Osage Orange) wheels were not desirable on the plains.

This statement is a complete falsehood. Bois d' arc is also referred to as ironwood or Osage orange. It's well-documented throughout the latter half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as being an important wood for use in wagon wheels. Inside the pages of "The Prairie Traveler," published in 1863, those heading west by wagon are given numerous recommendations for overland travel. Among the valuable tips in this guide was this counsel... "Wheels made of bois-d arc, or Osage orange-wood, are best for the plains, as they shrink but little, and seldom want repairing. As, however, this wood is not easily procured in the Northern States, white oak answers a very good purpose if well seasoned."

According to period publications, the natural range of the tree was from southern Arkansas through southeastern Oklahoma and down to southern Texas. A wider range of economic planting, though, reached out much farther, including the middle western states from Illinois southward and then westward to eastern Colorado and New Mexico. It's possible to be grown in more northern climates but harsh winters take a toll on the tree. Due to the continued interest in this wood, we're considering writing a lengthier article on its history, use, and significance.

20) Not all period chuck boxes utilized a folding leg(s) to support the hinged table.

While most period chuck wagons do appear to have used some variation of a folding leg to support the chuck box lid/table, there were exceptions to the rule. In our collection of pre-1900 and turn-of-the-century imagery, there are several original photos showing a chuck box equipped with either ropes or chains to hold the table level when lowered.

21) Round edge tires were common on wagons used during the Civil War.

This is a false statement and is one of the design technologies that can be helpful in narrowing down time frames of manufacture in early wagons. Notable manufacturers were touting round edge tires as new and innovative designs in the early 1880's.

22) Not all king bolts were made of a single, solid piece. Some were designed to bend.

As crazy as it may sound, this is true. Clearly, most king bolts on wagons were made from one, straight and solid piece of metal. Sometimes, though, the pin was shaped like a 'T' to allow the rocking bolster to move side to side without putting pressure on the main pin. Similarly, in 1884, Richard Blackwell of Kentucky created a king pin with a hinged joint to allow more fluid movement of the rocking bolster without undue pressure on the main pin.

23) George Milburn (Milburn Wagon Company) was related to the Studebaker Brothers through marriage.

In 1857, George Milburn needed help fulfilling a U.S. Army contract for wagons needed in the Mormon conflict in Utah. Milburn subcontracted the completion of 100 wagons with the up-and-coming Studebaker Brothers in South Bend. It was the beginning of an even closer relationship between the brands as Milburn's daughter, Anna, married Clement Studebaker in 1864. By 1868, the Studebakers had incorporated the business with Clement as president.

24) The California Gold Rush was started by a wagon maker.

This is a relatively obscure fact. James Marshall was a wagon maker long before he discovered gold at Sutter's Mill. Reinforcing that point, here's a brief article from the July 1890 issue of "The Hub"...

"The original discoverer of gold in California was a Jersey man. He had learned the wagon-maker's trade of his father, and went to California in 1845, when he was thirty-two years old. On the 19th of January, 1848, while engaged in the construction of a millrace at what is now the thriving town of Coloma, his attention was attracted by the glitter in the sand that had been washed down by the stream. He was a man of considerable practical knowledge, and soon came to the conclusion that the bright particles were gold. Not appreciating the significance of his discovery, he revealed it to his fellow-workers. Very soon afterward gold was found in paying quantities in several parts of California and the great rush to that State from all parts of the Union began. His name was James Wilson Marshall, and quite recently a monument was erected at Coloma, Cal., to his memory, near the spot where he first found the hidden treasure. It bears the inscription: 'Erected by the State of California in memory of James W. Marshall, the discoverer of gold."