The first time I saw the old stage, it stopped me. Like a ghost, it had my full attention. Barely a shadow of its former self, the ancient body was tired and ailing. Somehow, it made the journey from the gold rush days of 1860s Montana to the twenty-first century without being restored. Clearly, it had been through a lot. Like a tortured survivor from an action-adventure film, it was covered in battle scars, each one a reminder of Old West hardships. The wheels were heavily abused. The body bore deep wounds from leaning into the wheels on steep, sidling terrain. Tattered canvas hung listless from the roof. The interior upholstery was largely gone. Above the doorway darkened remnants of long-departed paint spelled the words, "VERGENIA CITY." Upon closer inspection, that misspelled name had been applied over another barely visible set of all-cap letters correctly spelling the single word, VIRGINIA. The rear boot leather was parched and hardened, cracked beyond repair. Even the front axle had been replaced and some parts were missing altogether. What this escaped fighter lacked in perfection, though, it made up for in western history.

Hailing from the days of Lincoln, Grant, Custer, Carson, Hickok, and Cody, this stage did more than just travel the frontier, it helped open it. Now, the wooden body was showing its age. Its sides were bulging, and the disheveled contours seemed to lean in every direction. Time, weather, and neglect had left the six-horse machine clinging to hope, yearning for someone, anyone to take notice. Decade by decade, it held on, ultimately becoming a phantom, virtually unseen and unknown.

1866 image of Virginia City, Montana - Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Yet, there was a day when this veteran stood proud. From Salt Lake and Salmon to Virginia City, Red Rock, and the Big Hole country in Montana, folks knew when he arrived and were just as mindful when he left. As he neared his fiftieth year, fire-wielding surgeons lashed steel to his bones, surrounding his upper frame with metal rods, bolts, and bars. It was an Iron-Man transformation of sorts; a process of reinforcing the stage so it could be loaded with heavy payloads and then run through the bogging stress of Montana's Big Hole region. Like a fraternal tattoo or familial trait, those same fortifications can be found almost exclusively on a half dozen other Mud Wagons with ties to the Big Hole Staging Company.

Those final glory days took place more than a century ago. Long enough that, today, this stage stands quiet, near forgotten and almost lifeless. Yet, for those who would listen, there is a faint whisper from yesterday. A dim, rasping voice, rich with stories of struggle, endurance, and raw determination; moments so immersed in the saga of the American West that survival, itself, may be this rolling icon's greatest legacy.

When I first became aware of this stage, it had very little documentation. We knew it had ties to Virginia City, Montana and that it had come from a museum in Billings, Montana. The once-popular attraction had ceased operations in 1961, almost one hundred years after this wheeled monument to the West was born. The full story of us tracing the history of the stage will likely be in a later book but, suffice it to say that, we've learned a lot since we acquired this set of wheels in 2019. Since then, my wife and I have traveled thousands upon thousands of miles chasing hope, looking for leads, hitting dead ends, and culling out unrelated clues. As of 2025, we've been fortunate to locate a sizeable portion of the vehicle's history. It's taken time, money, persistence, and an unbelievable amount of patience. Like the removal of ancient coats of overpaint, slowly but surely, we've been able to peel up the layers from the past, pulling this witness back from the brink of anonymity. Hopefully, this can be an encouragement to others with their own quests for primary source documentation.

While not every part of the stage's background has been uncovered, we do have sources aligning the beginning of this story with the days of Abraham Lincoln. In the early 1860s, the main ways to embark west of Missouri was by foot, animal, boat, or wooden wheels. Each had its own worries and no route was easy. Crossing 2,000 miles of plains, mountains, rivers, desert, and the unforeseen could be overwhelming. Nonetheless, the land was destined to be trod. Families, entrepreneurs, farmers, ranchers, trappers, politicians, and dreamers of all sorts wanted a piece of the pie. The transcontinental railroad did not yet exist and, when it came to law in the frontier, the same could often be said.

As war was raging in many parts of the U.S., the struggles of a nation not yet a century in age were tearing at the very fabric of the Union. In the hamlet of Concord, New Hampshire, two men - separated from their own previous time together - carried on with their stock-in-trade, the making of wagons, carriages, and stagecoaches.Their names were J. Stephens Abbot and Lewis Downing (Abbot Downing). By 1865, the two firms would be one again but, for the time being, they remained independent.

The shops of Abbot-Downing in the early 1870s. Image courtesy Wheels That Won The West® Archives.

Sometime during the Civil War, Mr. Abbot received an order for what he referred to as a Heavy Overland Mail Wagon. This has also been referred to as a Mud or Celerity Wagon and, in more general vernacular, a stagecoach. This set of wheels was to be built for the rugged and harsh demands of the American West. It was to be sized to accommodate nine interior passengers on three seats with the possibility of as many more folks outside. It was among the larger passenger-carrying stages. While Mr. Abbot's order books are lost to time, we do know the order number, 11911. That palindrome is stamped on the axle ends, driver's toe rail, and the kingbolt plate.

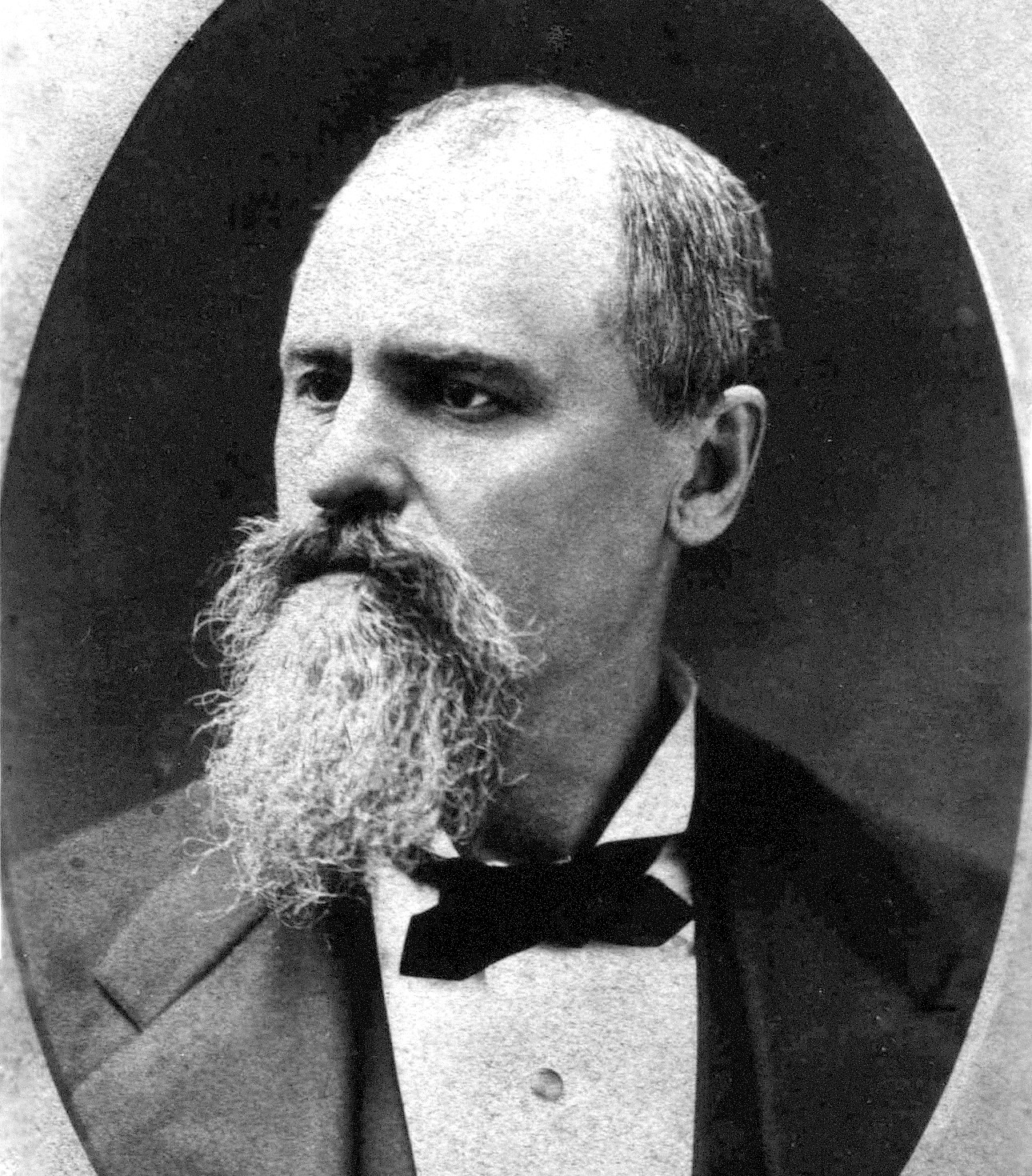

The first time we hear about this stage's travels in the West, it's 1864 and it's rolling from Salt Lake City, Utah to the new gold diggings of Virginia City, Montana. Gold fever not only promised opportunity but seemed to invite every ne'er-do-well and ruffian old enough to travel. The town was overrun with tens of thousands of opportunists. Among those looking to capitalize on the western growth was the legendary "Stagecoach King," Ben Holladay. He was running this route from Salt Lake, adding even more reach to his massive staging empire. Even so, he could see the days of stagecoach travel were numbered, and by 1866, he sold out to Wells Fargo, who eventually passed the route to Gilmer & Salisbury.

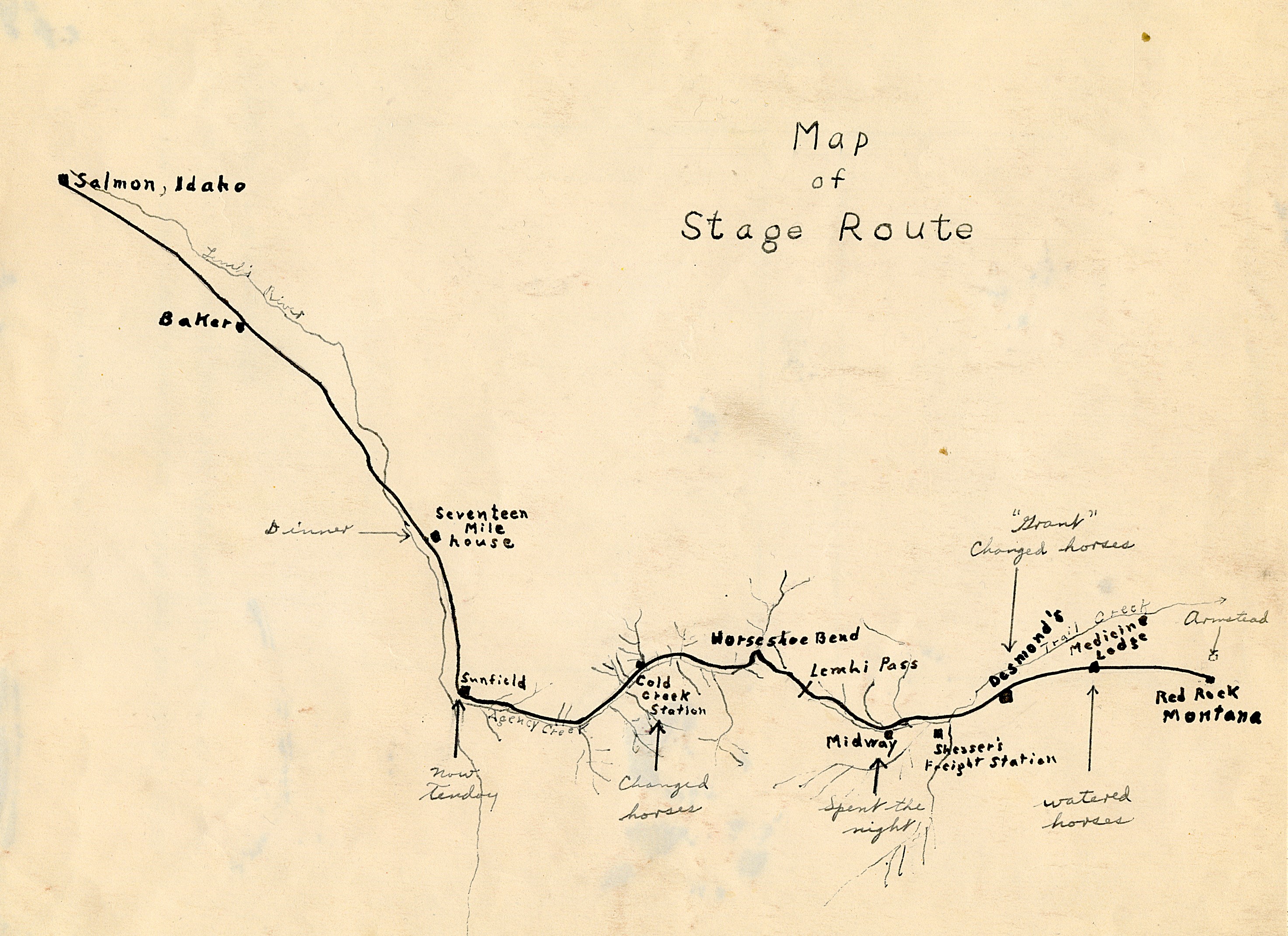

Scant details have been found on the length of time and different areas around Virginia City that 11911 ran but by the late 1880s it was still nearby, running over the Continental Divide between Red Rock, Montana and Salmon City, Idaho. Using the Lemhi Pass through the Rocky Mountains, the stage was photographed multiple times in different areas along the route.

Stories of wrecks, rewards, robberies, and runaways surround this traveler. In fact, the 1992 book entitled, "Centennial History of Lemhi County, Volume One," details one harrowing runaway that petrified the passengers as the stage broke loose from a heavy drag slowing its long, steep descent into Idaho. Efforts from the driver and brake were of no help in stopping the chaos. As the uncontrollable rig hurtled down, bumping and pushing the wheelers, one of the horses fell and was drug. It seemed the entire collection of voyagers - driver, team, coach, and passengers - were moments from sliding off the narrow trail and into the unimaginable depths below. Against all odds, the stage managed to stay upright and narrowly clung to the edge of the mountain. In spite of the close call, features on this survivor tell us plainly that this was not the only wreck it encountered.

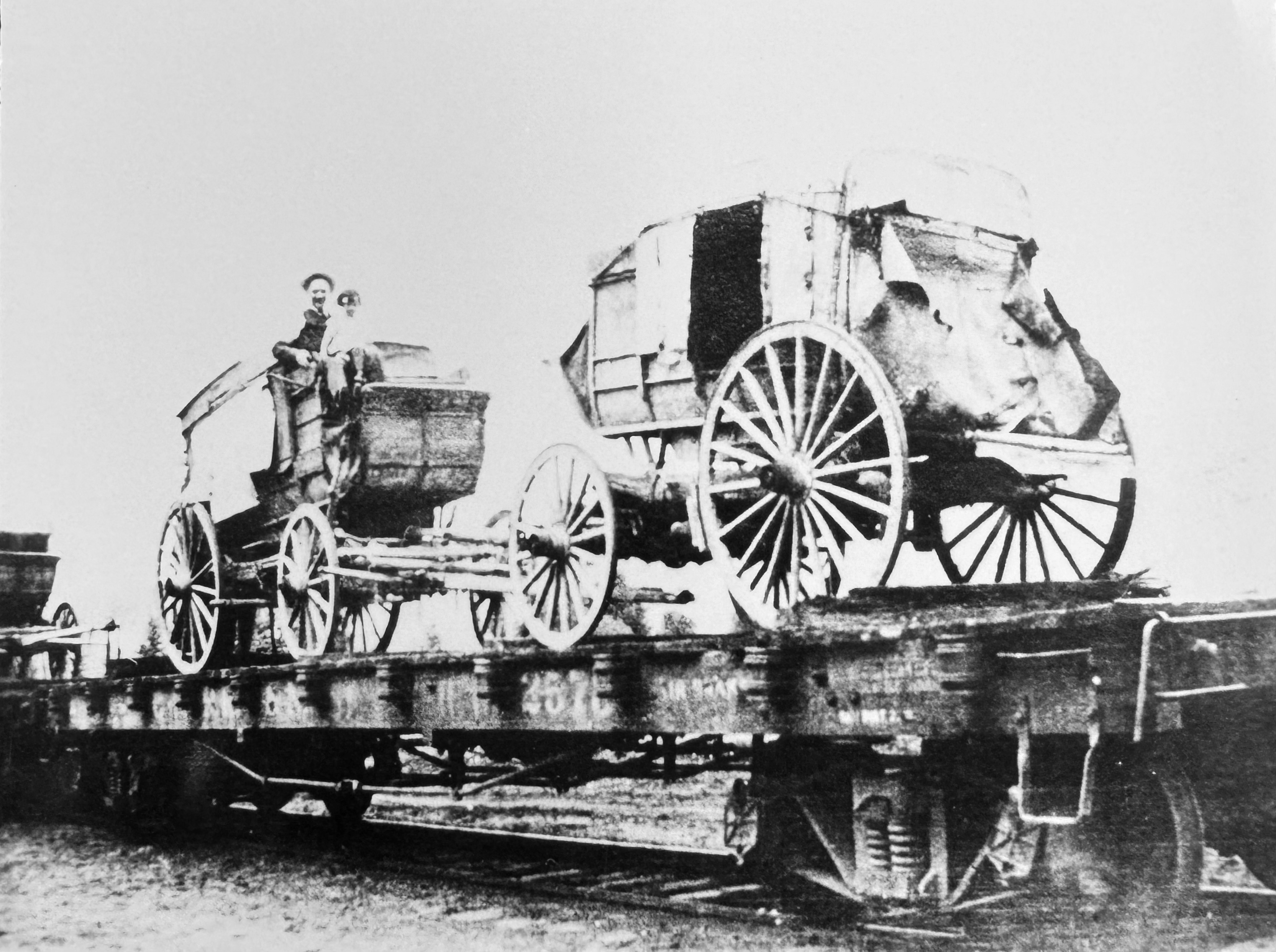

After leaving the Red Rock and Salmon line in 1910, there was one more area still needing express and staging services - the Big Hole region of Montana. The old stage remained there until it was retired around 1915. The photo immediately below shows it on a flatbed railcar with two other mud wagons. We believe the sister coach in the foreground to be the same one that was restored and recently purchased by the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman. 11911 is the one in the middle with the elderly man and child on the box.

After more than a half century of service covering almost the entire era of western stagecoaching, 11911 was retired, only to eventually be pulled back out and frequently driven in the 'Go Western' parades in Billings, Montana during the 1930s and 40s. A 48 by 80-inch painting of the old warrior was completed by legendary western artist J.K. Ralston in 1950.

From roughly1950 until 1961, the historic set of wheels could be seen in the Wonderland Museum in Billings, Montana. This museum was owned and operated by well-known western heritage collectors, curators, and historians, Don and Stella Foote. When the museum closed in '61, the stage was put into storage and all-but-forgotten until it was sold in 1978. The new owner was fascinated with all things western and relocated the piece to southern California. There, in the shadow of Hollywood, it sat until six years ago when we began retracing the tracks of this part of our past.

As of 2025, we've spent years digging into museums, newspaper archives, online auctions, and the files of historical societies. We've interviewed numerous folks, including the gentleman who purchased the stage in 1978. Along the way, we've been able to piece together quite a collection of facts and artifacts. The search, itself, has been quite a ride and has its own colorful stories. We've even been extremely fortunate to find several handfuls of aging photos showing the old stage at work in the West. This post includes a few of those images.

Illustration showing the old stage route from Red Rock, Montana as it traveled over the Continental Divide and into Salmon City, Idaho. Image Courtesy of the Lemhi County Historical Society & Museum, Salmon, Idaho.

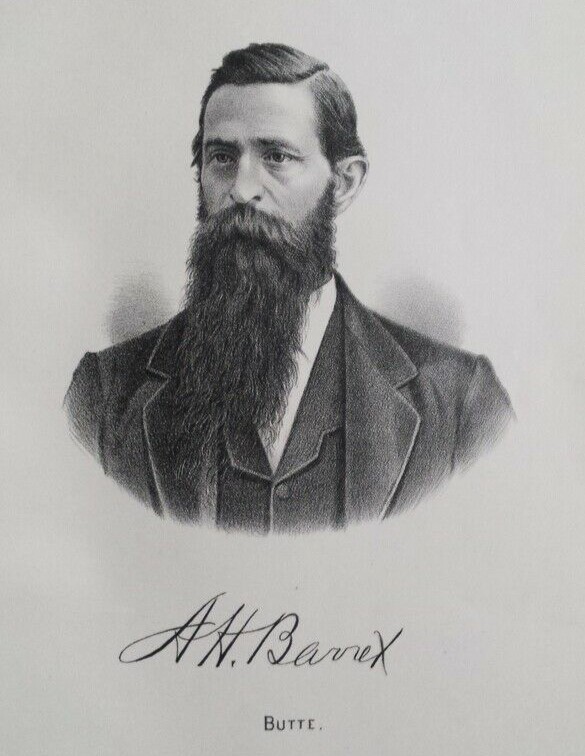

Beyond the stage, itself, what lay inside it has been equally intriguing. When I picked up the aging centenarian, incredibly, nothing in it had been touched since it left the museum in '61. For nearly six decades, it simply sat. It was a time capsule holding parts of the past that most of us only read about. Among the treasures in the body was a full six-up set of period coaching harness. A loop on one set of harness is stamped with the maker's name, A.H. Barret - Butte, Mont. It's a mark that easily dates to the 1800s and perhaps as early as the late 1870s.

Tracing the latter years of 11911 brings us to 1910 when stage service between Red Rock and Salmon, Idaho ceased. The railroad had finally taken on much of those duties. Today, though, it's still possible to travel on or close to that old stagecoach route and even stand atop the Continental Divide between Montana and Idaho - taking in almost the exact scene as Lewis and Clark did in 1805 when they were guided by Sacajawea. Here, also, I've straddled the beginnings of the western-most waters of the great Missouri River. It's inspiring to be surrounded by so much of America's western history and, likewise, a reminder of the responsibilities we have to share these moments with future generations.

While we haven't stopped our search and rescue mission, I wanted to pass along a little of this history because some exciting things are happening. This week will mark another milestone in the story of 11911 as it begins its path toward repairs and conservation work. The old scars and age stains will remain but parts of the stage need a reset to preserve the original for the next century. After all, this is a set of wheels that literally lived the Old West, running throughout parts of Montana, Idaho, and Utah for virtually the entire era of western stagecoaching.

Ultimately, some history can be hard... Hard to see, hard to experience, and even hard to imagine. In this case, 11911 is a time machine of sorts. Looking close at the old set of wheels, soaking up the pockmarks and disfigurements; seeing the crackled, 160-plus-year-old paint on the perches; the smooth depressions of a well-worn driver's seat, bent lamp post, worn foot brake, and even reading first-hand accounts of its history - all of it takes us back. Back to a time that Hollywood continually strives to recreate and reimagine. But, this set of wheels doesn't need to imagine. It was there in the midst of the wild. It's the kind of connection that helps reinforce the lure of the West while also reminding us of just how harsh those times were.

Have a great week and I hope you enjoy these images from America's past. In the meantime, we'll keep you abreast of the progress with the old stage. Reinforcing the action-packed western films of our day, this part of our past just might have been the Last Stage To Red Rock.

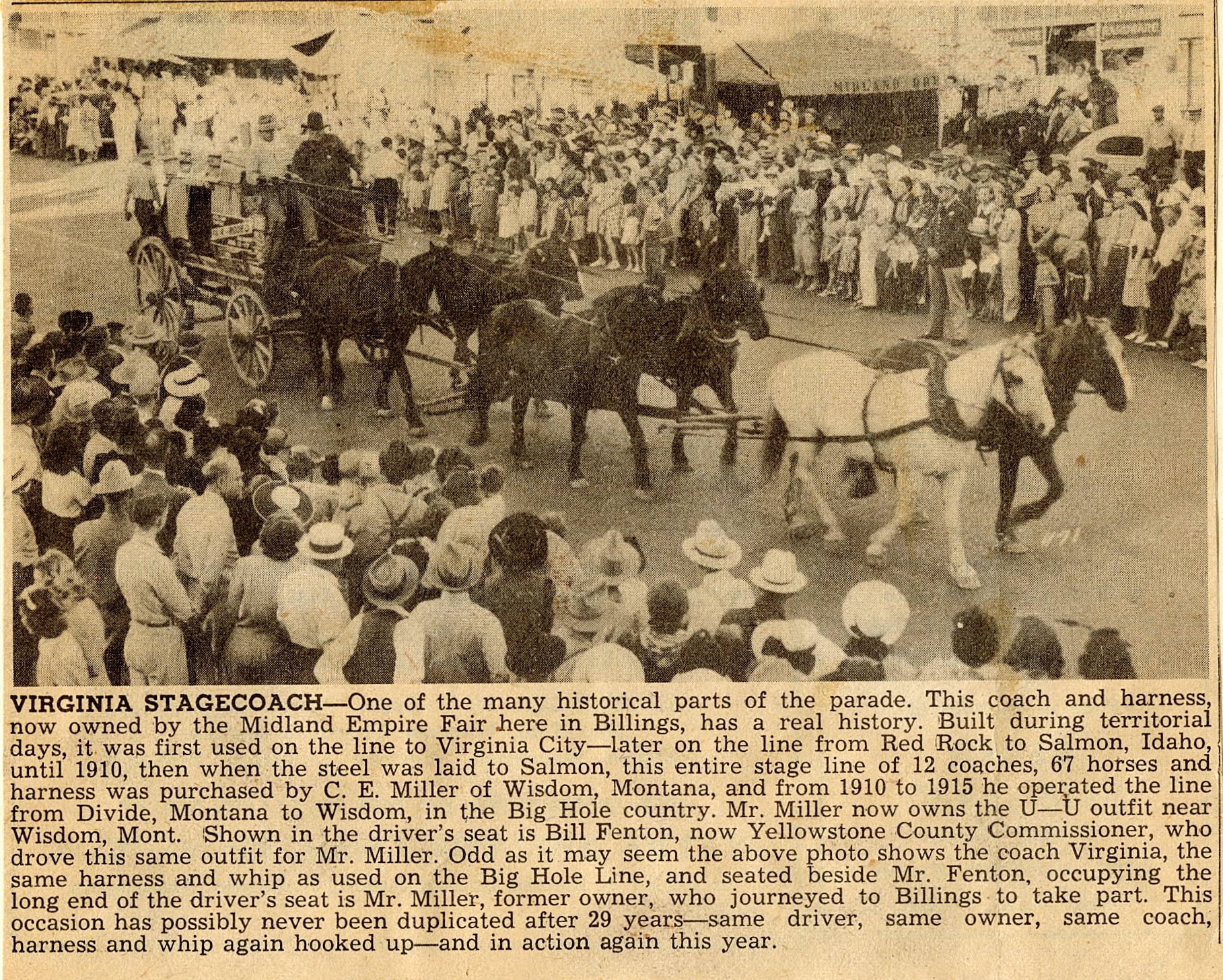

This news article covering the Billings, Montana parade in 1944 helped provide a wealth of information for us to further track the history of stage 11911. This is from the June 13, 1944 issue of the Livestock Reporter. Image Courtesy of the Lemhi County Historical Society & Museum.

Psalm 20:7