We hear a lot these days about the‘transition’ team that America’s newest President is assembling. The process marks an event that takes placeat least every 8 years and sometimes as part of a 4-year cycle – depending onthe outcome of a particular election. When it comes to product innovation or industry transformations in theU.S., though, the sequence of events isn’t necessarily routine or predictable. Such was the case for the massive transportationindustry during the dawn of the 20th century. At the time, many in the horse-drawn era found themselves surprised atthe influence and excitement heralded by the new, internal combustion machines. They couldn’t fathom a total transition tomotorized power and, as a result, they were largely unprepared for thechange.

Overall, it’s an understandableperception. With almost 200 years of this country’s history being dominated by horse-drawn vehicles, a sizeablenumber of folks had become hard set in their ways and felt things should remainthe same. Even so, it was aseverely-limiting paradigm forming a lot of its own barriers to growth andsuccess. Generations had grown up usingthe products and had become financially dependent on the industry. So, when a new, more advanced form of travelbegan to gain traction, the transformation was an unfamiliar and uneasy one fora large number of folks. It was also onethat required more capital for start-ups. So, it’s not all that surprising that some found it a hard propositionto warm up to. At the same time that somany were grappling with fears and resistance, others embraced and participatedin the movement while still more waited to see what would happen.

|

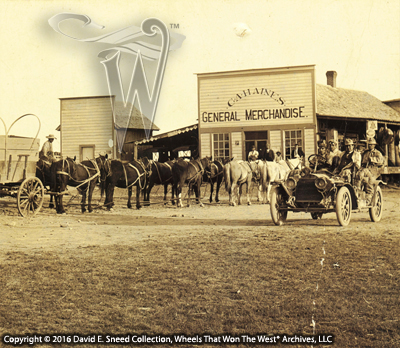

The early 1900’s amounted to a collision of worldsbetween horse-drawn and motorized transportation. |

The study of this part of our historyreminds me of the old adage pointing out that there are just 3 kinds of peoplein this world… Those that make things happen. Those that watch what happens. And those that wonder what happened! Ultimately, those early days were a tumultuous time filled with rivalries, litigation, questions, and plenty of folks watching and wondering what the devil was going on.

During the early 1900’s, there werehundreds of U.S. companies fighting for success in the newly-formed autoindustry. Ultimately, almost all of themfailed. Along the same lines, there weretens of thousands of horse-drawn vehicle makers and repairers struggling withtheir own perceptions of the horseless carriage. For some, it was a fad. For others, the vehicles were a luxury thatwould never be affordable. Tradepublications initially decried the evils of motorized transportation. Salesmen missed no chance to deride the rubber-tired dragons whether they were gas, steam, or electric. Associations banded together to see whatmight be done to slow or stop the acceptance of these new-fangled machines. Articles were written discussing the noise,smell, cost, speed, power, unreliability, and other challenges associated withautomobiles – some of those things continue to be a point of reference!

|

The earliest Flint wagons were adorned with scenicmurals similar to those found on Concord stagecoaches. Like many legendary brands, quality Flintwagons are now among the most difficult to find. |

Studebaker, for instance,not only designed and crafted cars, trucks, buses, and bodies but also builtaircraft engines during WWII. They hadbegun working on their own automobile in the late 1890’s, making every effortto continually reinforce their role as a transportation king pin. After they ceased building wagons in 1920,they sold the related equipment and patterns while leasing their name toanother powerful brand – the Kentucky Wagon Company of Louisville,Kentucky. This move not only gaveKentucky another strong wagon brand to sell but provided a way for Studebakerloyalists to access original parts and maintenance on wagons that had beenbuilt in South Bend.

Speaking of Kentucky (Wagon)Manufacturing Company; from their beginning in 1879, they were a force to bereckoned with. Not only were they wellcapitalized but they were strong marketers producing tens of thousands ofwagons per year. During the 1930’s, thecompany was even more diversified as they took charge of Continental CarCompany, producing a wide array of train cars. The firm also made numerous early truck bodies and trailers, not tomention the manufacture and support of a full line of Dixie Flyerautomobiles. The direct descendant ofKentucky Wagon Company – Kentucky Trailer – has not only has survived but thrives as a dominant force intoday’s trucking, specialty trailer, and body industries. In fact, from commercial, medical, military,and government applications to motorsports, mobile broadcast production, moving& storage, package delivery, and enclosed auto haulers, Kentucky Trailerhas been called, “the most innovative custom trailer manufacturer in theworld.”

In Flint, Michigan where much of the20th century auto industry eventually found a home, the owners of Flint WagonWorks also launched a plan to build cars in the first decade of the newcentury. This was done during the sametime they were building wagons and the public was assured that they wouldcontinue manufacturing these vehicles just as they had since 1882. Ultimately, the old wagon factory served asthe origin of some of the earliest Buick and Chevrolet cars.

In Elizabethville, Pennsylvania, the Swab Wagon Company is still in businesswith the same name it carried in the 1800’s. Like many others, Swab became actively involved in building bodies forearly autos. The company built theirfirst fire-related vehicle in 1890 and, today, they specialize in theproduction of emergency vehicles for police, fire, and rescue needs as well asanimal transports and utility bodies. With roots to 1868, the brand is still family-owned and stands as one ofthe country’s oldest continuously-operated transportation manufacturers.

Located north of Hannibal, Missouri onthe eastern bank of the Mississippi River, Quincy, Illinois is home to a pairof extraordinary survivors from the early wagon industry. One of the oldest businesses in the citytoday is Knapheide. Established in 1848 as Knapheide WagonCompany, the firm is well-known for its truck and van bodies, utility beds,truck caps, and tool boxes.

|

| As evidenced by this 1891 patent, innovationand a strong quest for excellence were a big part of Titan International’s DNA fromthe beginning. |

Another of Quincy’s amazing successstories has deep roots in the tire and wheel industries. Tracing its foundations to 1890, Titan International began life as the Electric Wheel Company. As such, the company was an early producer ofinnovative metal wheels, wagons, tractors, crawlers, truck bodies,semi-trailers, rubber tires, carts, portable motors, and numerous otherproducts. Today, the firm is a powerfulmainstay producing tires and wheels for agriculture, construction, forestry,mining, ATV, and lawn and garden applications. As such, they supply tires and wheels for many well-known brands likeJohn Deere, Case, New Holland, Kubota, and Goodyear.

So, there they are. Just a few examples of how America’shorse-drawn wagon brands worked to overcome the trials of changing times. Like so many early auto firms, most wagon buildersmet their demise by or during the Great Depression. Nonetheless, as we’ve shared in today’s blog,a number of survivors have built strong foundations in the moderntransportation industry. Truth is, Isuspect there are more companies with roots to wagon and carriage-making stillaround today than those who actually started out building automobiles. It’s certainly an interesting suppositionthat points to even greater resilience and marketing savvy than many of ourcountry’s first auto makers.

From field and farm to the highways andback roads, America’s early horse-drawn brands took on an overwhelmingchallenge to re-make themselves with reliable and relevant offerings. It’s a heritage that’s been well rewarded withproven products, disciplined management, and forward-thinking momentum. Ultimately, it’s no real surprise. After all, that same focus on excellence,achievement, and customer satisfaction is what drove America’s first wheels tosuch prominence in the first place.

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC