Did they or didn't they, could they or would they, should we or shouldn't we... Week after week, we're quizzed about different vehicles and technologies represented on the American frontier. Many of the questions are related to when, where, and how as well as what is appropriate for everything from chuck wagons and stages to Sheep Camps, military wagons, and freighters. Since no one is alive from the nineteenth century, before we can confidently relay the way things were done in the 1800s, we need to sharpen our research skills and focus on the only survivors of that timeframe - Primary sources. Ultimately, it's why we've worked to build such a large collection of original, maker materials for our Wheels That Won The West® Archives.

Primary source credentials are resources that derive from a particular timeframe of study, providing us with a firsthand account of true experiences. When it comes to horse-drawn vehicles, that original documentation can include photos, guidebooks, diaries, newspaper accounts, personal letters, business correspondence, patents, trademarks, catalogs, trade publications, promotional objects, ledgers, unrestored vehicles themselves, and countless other items. Individually, each can be helpful. Collectively, they are invaluable assets, helping restore a more complete picture of America's first transportation industry and associated western vehicles.

Shown are a few of the hundreds of original wagon maker catalogs and promotional materials in the Wheels That Won The West® Archives. This abundance of primary source content helps discern fact from fiction as well as what happened and when amongst the more prominent nineteenth and early twentieth century builders.

Those very materials are how we can determine the difference between an 1860s or 70s-era Army Escort wagon and one built in the twentieth century for World War One or Two. It's how we can separate wagon designs built in the 1900s from the majority of those constructed during the cattle drives of the 1860s, 70s, and 80s. It's how we can see geographical differences in wagons made for a particular part of the country; east, west, or in-between. It's also how we discern one brand from another and, ultimately, how we uncover and authenticate the story of a particular set of wheels.

The whole process of discovery is fraught with trips, traps,and treasures. One of the first challenges to overcome is to avoid viewing yesterday through modern eyes. In other words, we need to be immersed in the timeframe to fully understand the product, places, and people of that period. Along with that thought, comments like 'rare' and 'seldom seen' should be tempered by confessions as to how much study a person has done on a subject. Case in point, when I first started my own research journey, there were a lot of things that I had 'seldom' seen. Intensive, daily research for more than three decades, though, has grown awareness to the point that distinctions jump out and familiar calls out. I've described those areas before as being like meeting an old friend. Even if it's been a while, you can still recognize the person that you remember.

Timeframes, locations, brands, and technology can all affect the overall design and individual features seen on a period vehicle. With constant research, many of the areas that, initially, may seem foreign will become familiar. Time and the intensity of searches will gradually reveal what truly makes up the scarcest parts of our wheeled past.

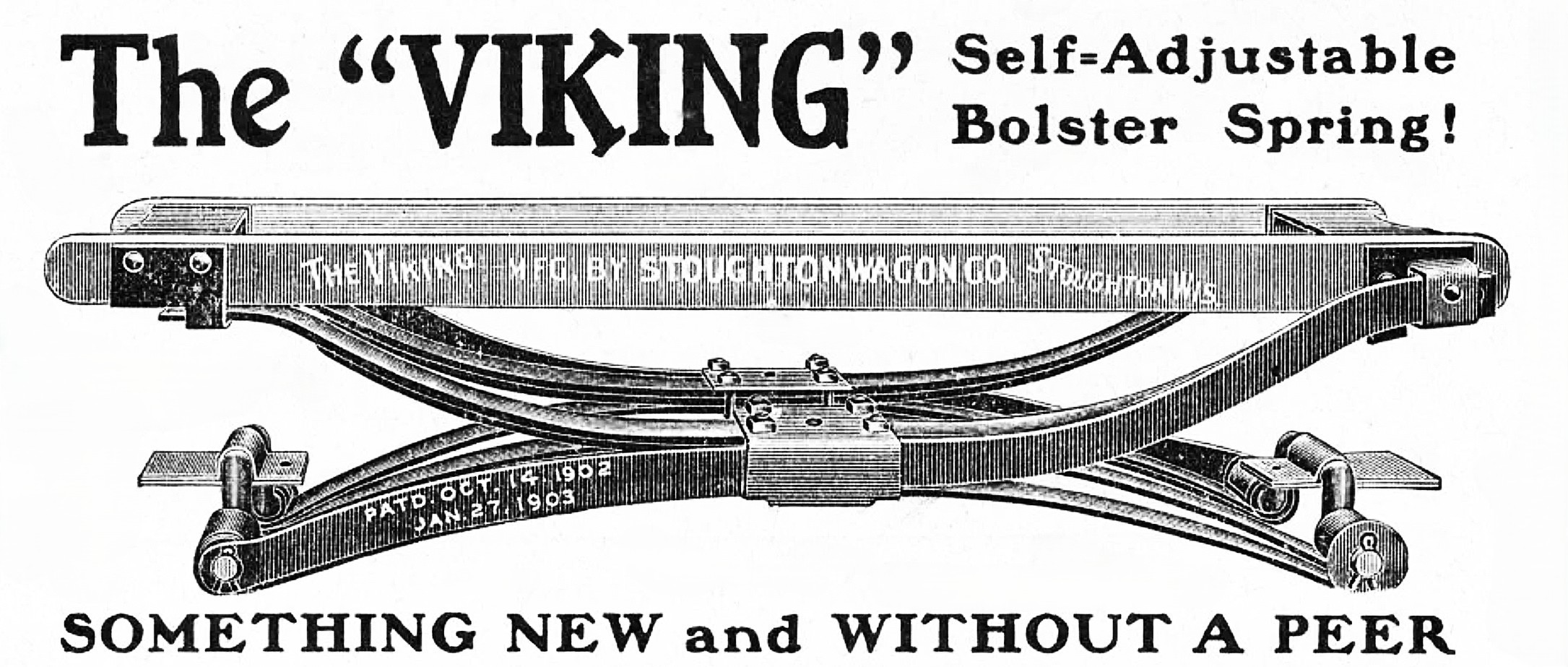

This general style of bolster spring is most common among enthusiasts today. Earlier designs from the nineteenth century were often a little different.

As part of our research, we receive a lot of questions. Among those are ones asking about the use of springs; specifically spring seats, bolster springs, tongue springs, end gate springs, and even springs on brakes. While some spring technologies did have beginnings in the 1800s, the actual development of springs began long before American cowboys, outlaws, freighters, miners, emigrants, trailblazers, and even early explorers were trekking across what would become the United States. This doesn't necessarily mean that a spring design we're familiar with today was also prevalent at a particular earlier date. Know-how and engineering within any craft has a way of evolving and different eras often touted different designs. Understanding what happened and when can be tricky. Many times, it requires a firsthand examination of a specific piece rather than a blanket answer to a general description.

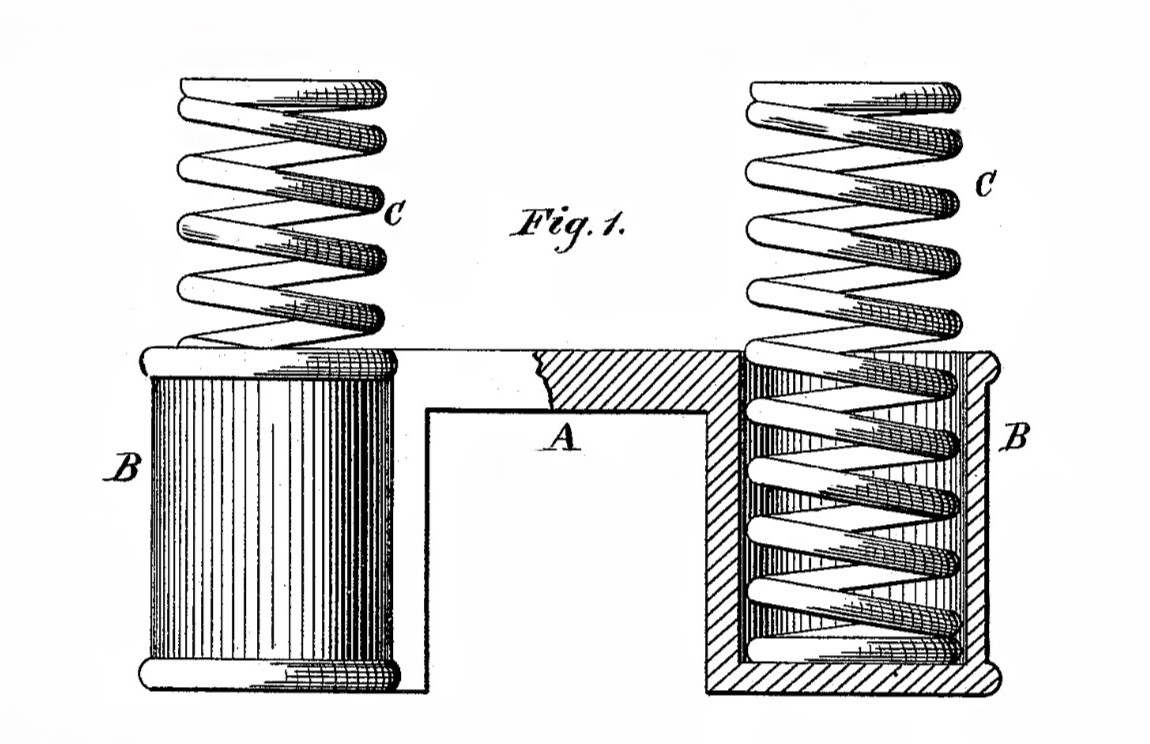

The images above are from an 1834 patent for leaf springs on rail cars.

For instance, as a basic reference, spring technology is as old as the bow and arrow. After all, at its core, a bow is a spring. Even ancient Egyptian chariots are known to have used suspension systems that functioned as springs. While it looked different than what we're familiar with today, leaf spring technology will date to at least as early as the Roman Empire. Coil springs were patented in 1763, and patents for a multitude of spring designs are plentiful in the 1800s. In the U.S., we find a leaf spring patent for heavy railroad cars as early as 1834. A method for creating elliptical springs was patented in 1838 and other carriage spring designs will date even earlier.

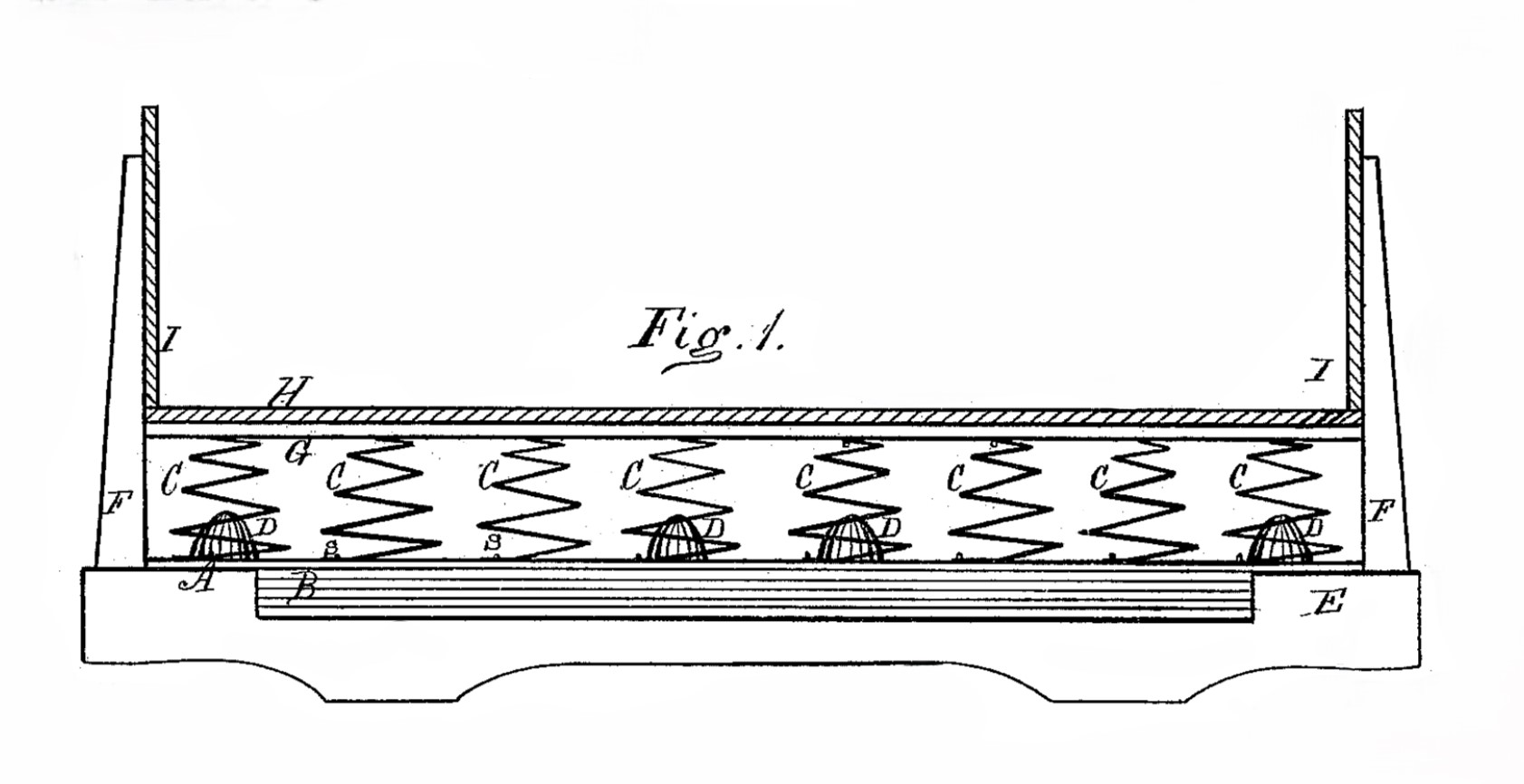

From an 1867 patent granted to Jacob Beck of Williamsville, Illinois, we know that wagon seats with springs were already well established by that time. In fact, as early as the 1820s, variations of wagon seat springs were being developed. The 1867 patent states that, "... many devices have been adopted to give elasticity or a spring to wagon seats; and elliptic steel springs, half springs, spring poles, and other devices, have been used to overcome the severe jolt of having rigid wagons..." This same patent clearly shows the use of barstock seat hooks (similar to what we see in the late 1800s and early 1900s) which allow the seat to be quickly removed. How early did the removeable spring seat start? The earliest times may be challenging to determine but the Civil War did seem to jump start a lot of product development and ingenuity. As far as elliptic springs on seats go, by 1869, sources within our Archives are describing these as 'common.' Based on patents, earlier documents, and this reference to the ubiquitous nature of elliptic springs during the 1860s, it seems clear that elliptic seat springs were likely in use during significant portions of America's mass migration into the West.

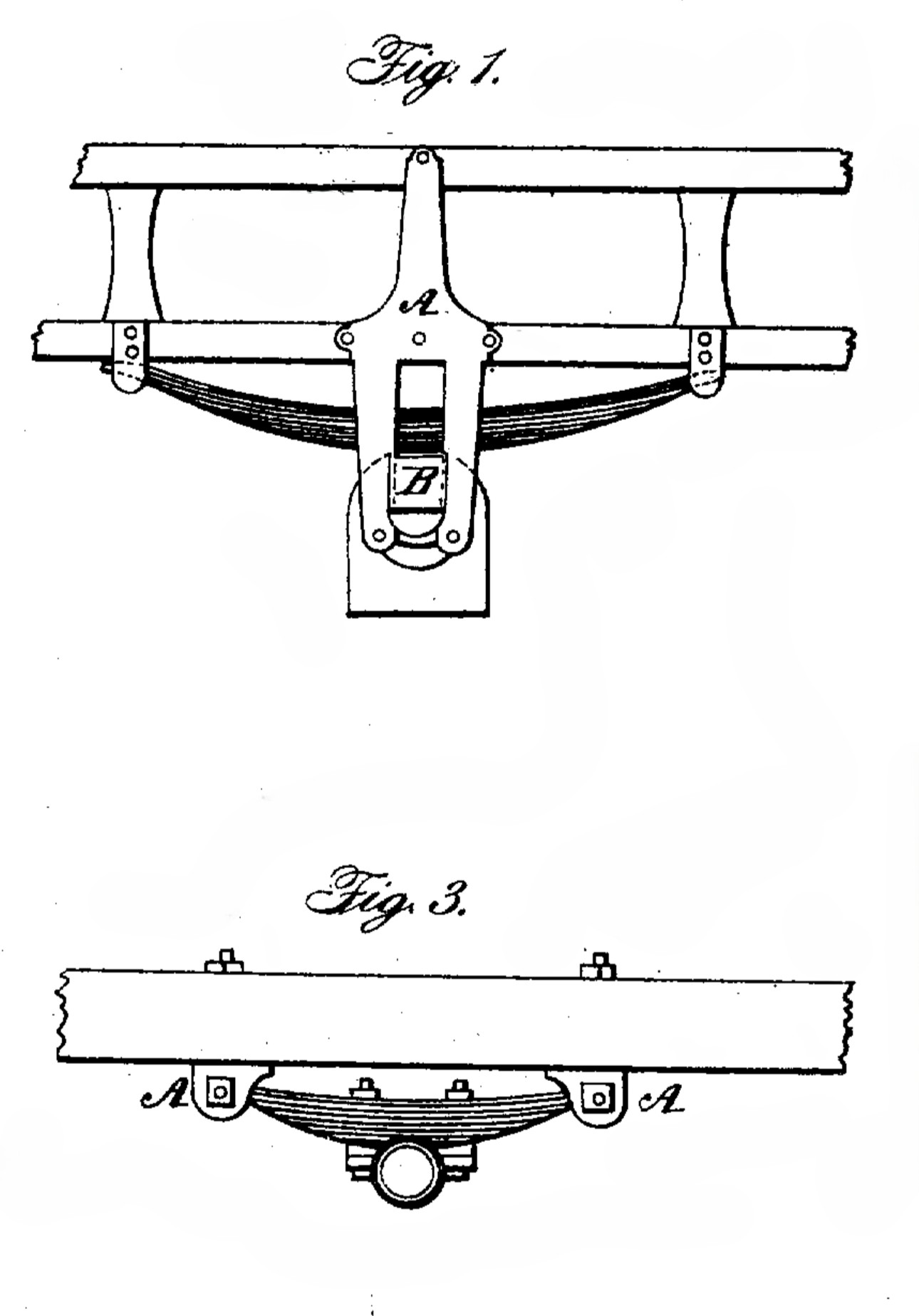

Bolster springs for wagons can be traced to at least as early as the 1850s. This 1866 patent illustration is similar to twentieth century designs but still has notable differences. Other configurations included coil springs and rubber suspensions.

On a similar note, over the years, I've heard a number of discussions related to bolster springs; with some even questioning whether they were used in the 1800s. Among the layers of evidence, there are patents that can be traced to as early as the 1850s. With all of this said, a fair number of these initial spring designs will have a different look than the more common survivors today. While most period photos of chuck wagons do not show the use of bolster springs, the Studebaker Bros. Manufacturing Company did build a chuck wagon they referenced as a 'Round-Up' wagon. It was marketed in the early 1880s with bolster springs positioned between the box and front/rear bolsters. One of the earliest chuck wagon images in our Archives also has these springs. It will easily date to the 1870s. Again, while bolster springs on chuck wagons do not appear to be common, it clearly did happen during the 1870s and 80s. It's not overly surprising as these wheels were personal approaches to a particular need. How individualistic were chuck wagons? Well, even the massive Studebaker Bros. business recognized that these vehicles could be different, depending on the end user and location of use. In one early 1880s brochure, the company states, "As there are such a variety of tastes to be consulted as to extras to be supplied with this (Chuck) wagon, we leave prices to be furnished on application." At the end of the day, this is just part of the challenge when trying to nail down what any customized vehicle might have looked like. As a side note, the American Chuck Wagon Association has done a valient job of researching the ways so many of these vehicles were outfitted and designed.

A few months ago, I wrote a story called, Taming TheTongue. See the "Articles" section on our site. In that write-up, I covered a number of tongue spring patents, their purposes, advantages, and unique designs. From who did what to how and when, it's a portion of the western landscape that can be tough to navigate, with plenty of opportunity for misdirection. Ultimately, every part of an antique vehicle has a story to tell. Dissecting the pieces and letting each part of a wagon or stagecoach share its history can reveal valuable details. No matter the wheeled history, though, without primary source support, any proclamations are only guesses and speculation. Documented backgrounds can be tough to confirm but they're crucial in the work to preserve historical truth for future generations.

A respectable price but questionable brand claim.

As an example of the point above, my daughter is always looking out for her dad, sending photos of 'finds' she comes across. Recently, she was in an antique store and sent a photo of a spring seat for a wagon. There was no original paint or name on the seat, but a sales tag boldly proclaimed it to be Studebaker. I'm sure it was someone's best guess but there was literally nothing about the piece that mirrored Studebaker construction - from any timeframe (and, yes, every part of a Studebaker seat evolved over time). On this particular seat, the springs were wrong, the seat design was wrong, the wooden seat back was full of knots, and the entire piece had been repainted, albeit years ago. It appeared to have a reasonably solid base but it would be impossible for someone to justify and objectively support the maker claim. For enthusiasts, collectors, historians, and even casual observers, when it comes to authenticating wood-wheeled wagons and their parts, it's still the Wild West out there! Stay alert and be careful of what is pitched as fact. Fables are frequent, knowledge is power, and you may still find yourself asking, "Did they or didn't they?"

This image shows bolster springs positioned between the wagon bed and bolsters. Bolster spring designs were promoted at least as early as the 1850s in the United States.

BE AMONG THE FIRST to know when we've updated our blogs, articles, products, and other sections. Some things can be time-sensitive so it's good to be in the loop. To help ensure you're up-to-speed with our postings, just click on the SIGN UP banner at the top right of our website and leave your email address. It's quick and easy.

One more bit of housekeeping... for those who have tried to reach an Archived Blog through the tagged insets on our blogs, we're having some coding issues that are resulting in Errors. If you've experienced this, I'm sorry. We're working on it but due to the sheer number of stories, it may take our folks a bit to get them all corrected. The good news related to this problem is that ALL of our 'Wheels' blogs and articles are still directly accessible through the Current and Archived sections. It's only the sidebars/individual story insets that appear to be the issue. In the meantime, thank you for your patience.

David

Psalm 20:7