In the same way that artifacts connect with archaeologists, creatives see beyond a blank canvas, and historians help bring the past to life, there is something about America's first transportation industry that is captivating to me. It's the story of people with a drive to create and desire to better themselves and others. With that shared, I've said this many times, "Old wagons talk to me." Quietly whispering, they're full of facts and hidden information. Every part of the whole has a story to tell and learning where to look and what to look for can open a world of details related to the maker, user, and time period. Even with obvious markings worn away, methodical reviews can reveal everything from when they were made to where they were used, what they were designed for, who made them, and more. Inside and out, antique wagons have a language all their own. Understanding how to engage and connect with these time travelers can easily enrich our picture of the past.

Even with that knowledge and opportunity, we live in a world that persists with attempts to pigeonhole people, places, and things into basic, easy-to-digest explanations. The problem with many of those efforts is that most folks, as well as the subjects we study, are more complicated than a quick soundbite in a news clip or social media post. Likewise, the world of old transports is full of ambiguities with plenty of quicksand, desolate terrain, and sudden drop-offs along the research trail. With that said, one of my past blog posts, Western Freight Wagons, seemed to open the door for a few questions on Conestoga wagons. First of all, a 'Conestoga' wagon by literal definition is a larger and heavier freighting vehicle. It was also used in early military ventures. It is not a prairie schooner, twentieth century wooden farm wagon, or 1800s emigrant wagon. An actual Conestoga was a commercial vehicle used for hauling goods and materials. With that said, it is possible to find farm wagons of the era being referred to as a Conestoga during their days of use. It's no different than a mud wagon being referred to as a Concord coach during the days of stagecoach travel. There were different reasons for the blending of terms. Some was a general lack of concern for details while, at other times, there were attempts to frame a lesser vehicle with the name and reputation of a more notable one. The differences are clear but connotations of the day could (and still can) be easily blurred.

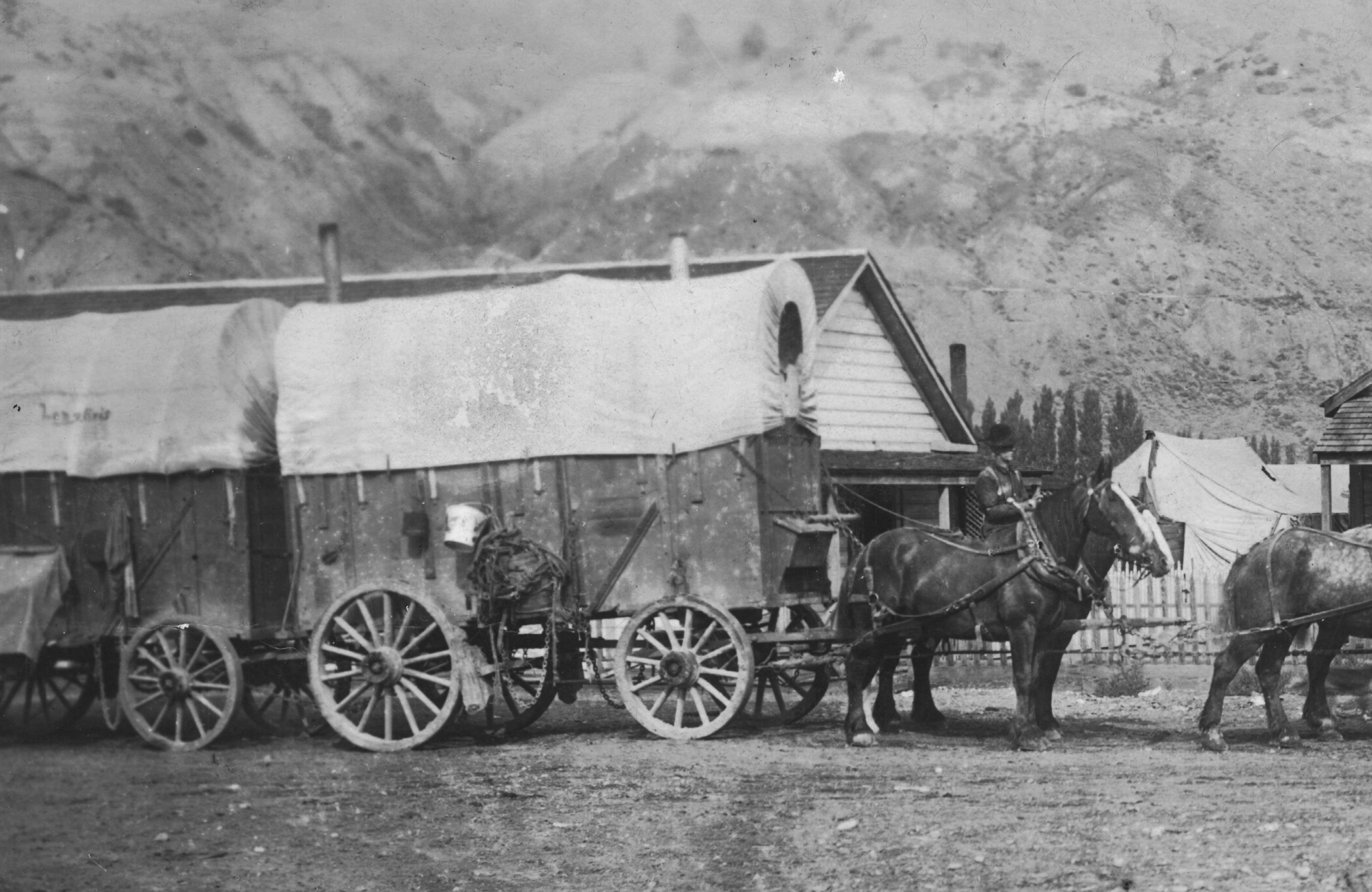

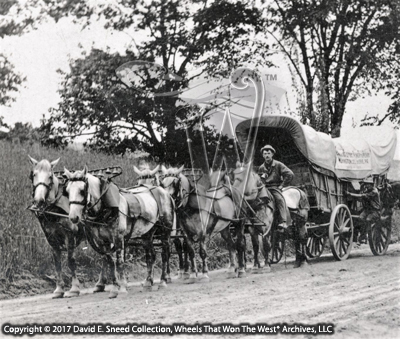

The upper image here shows later, tall-sided western freight wagons while the lower image profiles an earlier Conestoga freighter.

When it comes to the earliest production, there were no factories churning out these machines. Each was handmade, one at a time, in wainwright, wheelwright, and blacksmith shops and most were in use between 1750 and 1850. The origin of the vehicle is believed to be from the Conestoga River region in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. According to the Susquehanna National Heritage Area, the first known use of the Conestoga term with wagons was in December 1717 when James Logan recorded his purchase of a "Conestogoe Waggon" to bring loads of furs from his trading post on the eastern frontier to "Conestogoe." The vehicles were largely used to ferry goods to markets in Philadelphia.

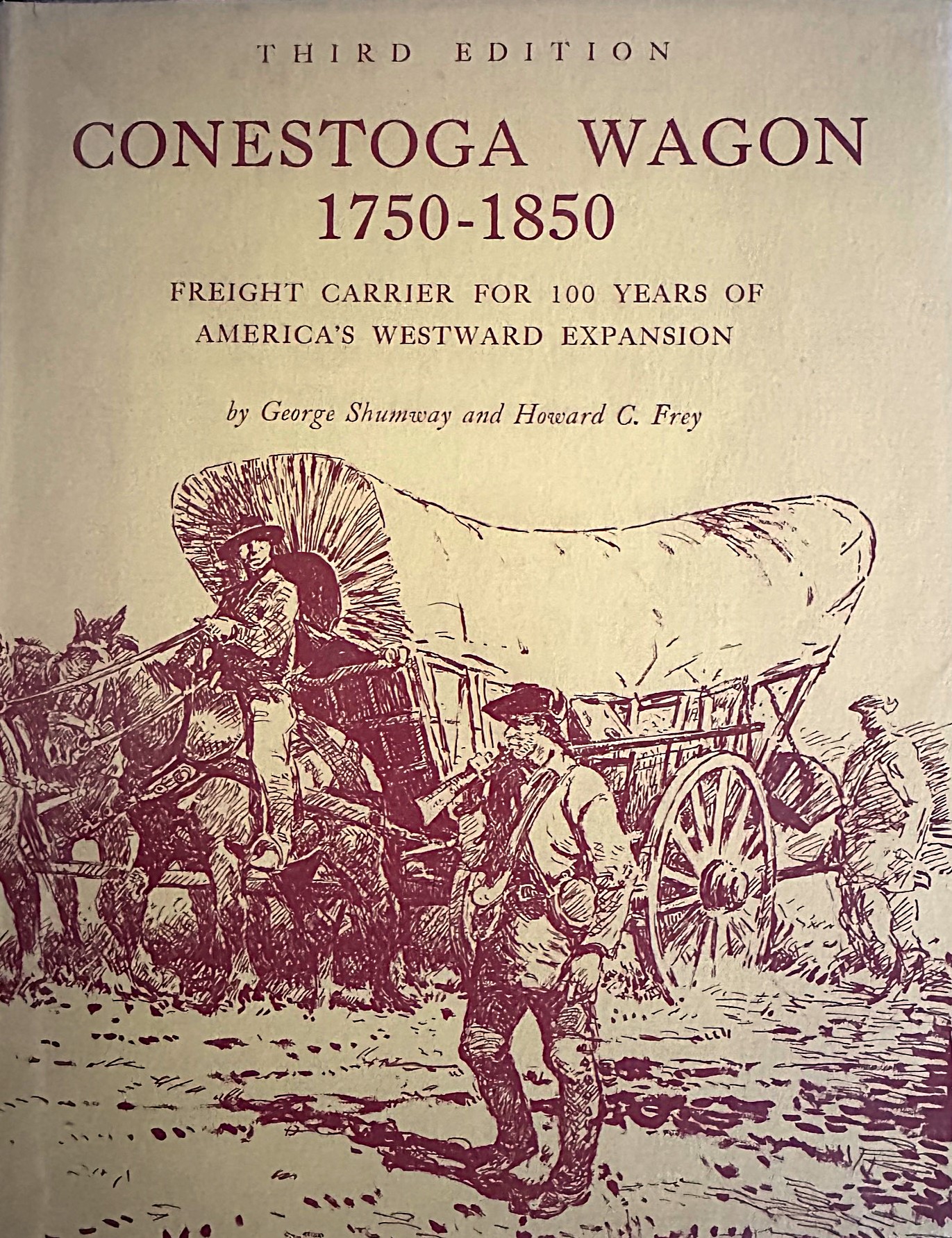

So, what features make up a Conestoga? While the earliest of these vehicles would have been seen with straked tires versus the more common continuous tire (metal band around the entire wheel), there are a number of other details that help identify these workhorses. Some of the best info can be found in a pair of books published decades ago. One is entitled, Conestoga Wagons,1750-1850 and the other is Conestoga Six Horse Bell Teams."Neither of the books are still in print but you can often find them in online auctions and antique book stores. Each is definitely worth acquiring for your early vehicle and transportation library.

The tool box on a Conestoga was often decorated with ornate iron work.

Looking at the wagon box, the construction will be of a rave frame design. As opposed to the flush sideboards with riveted hardwood cleats that are common on many surviving wagons, a rave frame bed will have a sort of exoskeleton to the sideboards, adding stiffness and strength to the box. The number of bows will generally range from eight to twelve with iron staples to hold the bows in place. The side rails and bottom of the box will be curved, sweeping up on both ends. This is a design that helped hold the contents of the wagon more securely in rugged, unimproved terrain. Both endgates are raked outward at the top, often with chipped edges for decoration and protection of the edges. There was typically a tool box on the left side, a feed box hung from the rear, and iron work could be very ornate on both the box, running gear (undercarriage), and accessories. In the earliest designs, mechanical brakes (rubbers), if included, did not feature removeable brake blocks as we see on most surviving wagons today.That feature came later in the use of most Conestoga vehicles. Overall, the complete list of features and variances are too involved to get into here but the book, Conestoga Wagon, 1750-1850, has a wealth of great descriptions that are more complete than this short blog.

With that said, there are some caveats, disclaimers, and similarities in other vehicles that we'll address to help minimize confusion...or, at least, point out some distinctions. One wagon type that carries similarities to a Conestoga is referred to as a 'Road Wagon.' This set of wheels was also used for freighting but it's a smaller wagon with less weight and more modest capacity than a full-size Conestoga. Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia has an excellent example of a period Road Wagon in its collection. Just to keep the pot stirred a bit more, there is another type of Road Wagon amongst early vehicle builders but it is nothing like the same-name freighter. According to Don Berkebile's book, Carriage Terminology: An Historical Dictionary, this additional Road Wagon is synonymous with references to an American buggy.

This schooner-style farm wagon includes an early running gear and a box (bed) that will date to the 1820s. It's located in New Harmony, Indiana.

The term, 'Prairie Schooner,' is another curved bed wagon that's typically associated with an earlier period vehicle. Effectively, these are farm-sized wagons that could be seen trekking across the U.S. With boxes bent in the rough form of a sailing ship hull and the covers being white, the term quickly caught on. These handmade vehicles were in regular use throughout the first half of the 1800s. While they have a curved shape to the beds, they are considerably smaller than a Conestoga freighter. There is an excellent example of the rave framed and curved shape of a schooner box in a collection in New Harmony, Indiana. It will date to the 1820s.

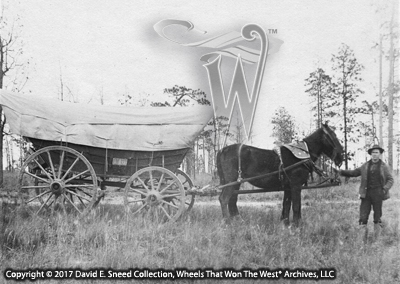

'Crooked Bed' wagons, such as the one above, were often used in the southeast U.S. for hauling tobacco and other light loads.

Another eastern-built vehicle that is sometimes confused with a Conestoga is the 'Tobacco Wagon.' Also called a 'Southern Schooner' and 'Crooked Bed Wagon,' this set of wheels has traits that can be traced to the Conestoga days. Even so, most of these survivors will be from the early part of the twentieth century. These boxes are considerably smaller than a Conestoga or even a Road Wagon. A 'Crooked Bed' wagon is even more lightly built. Typically, the number of bows will range between eight and eleven. Builders of this style of wagon include Spach Wagon Works in North Carolina, multiple Nissen brands in North Carolina, and others.

Finally, there are square-bodied farm wagons that have some Conestoga-type features, including a rave frame box. While typically an eastern U.S. design, these are not Conestoga freight wagons but they do share evolutionary features likely derived from earlier Conestoga designs.

This Conestoga can be seen at Bent's Old Fort in La Junta, Colorado.

From Mountain and Road wagons to rack beds, tall-sided western freighters, heavy farm wagons, log wagons, numerous dray designs, tobacco wagons, and the legendary Conestoga, there were countless wood-wheeled warriors responsible for hauling anything grown, eaten, worn, used, or mined. Recognizing the makeup of the vehicle design not only helps us understand its purpose but also its history. It's one more way that each of these pieces can 'talk' to us. WTWTW