Recently, a friend asked me how many images are in our collection of America's wood-wheeled history. After more than three decades of gathering these rare resources, our vaults are packed with visuals. Honestly, it's a little tough to keep count. The super-scarce black and whites are divided by brand/makeras well as the multiple categories of farm, freight, ranch (chuck wagons & sheep wagons), stage, military, business, and other specialized industry vehicles.With so many silvering reminders of the past, it's a little like Christmas morning every time I reopen a file. Similar to the vehicles, themselves, each one of these century-plus-old memories tells a story. In other words, there's a reason we were drawn to the original image and a significance as to why it's part of the Wheels That Won The West® archives.

Original, period photography, engravings, and illustrations may be in the collection because of the technology, advertising, event, personality, occupation, business, or brand shown. It might also be a scene preserving a unique situation or a glimpse into the life of a particular era or builder. I've also regularly used images from a specific timeframe to help authenticate existing paint styles, brands, designs, and even build dates. Whatever the reason for an image's inclusion in the archives, the goal has always been to save special parts of the past for continued study, understanding, and appreciation. Along with original vehicles, these images are survivors with valuable and undeniable insights into yesterday.

It's another reason we also have a large collection of early blacksmith and wagon shop photos. These frozen moments depict a time and lifestyle in America that will never happen again. Plus, it's amazing to stare into the time-worn faces and imagine the lives lived. Beyond the vehicles, the likenesses provide a study into almost every facet of life in that day, including problem-solving. I will confess, though, that the best and most amazing content is typically reserved for our in-person Power Point presentations. Much of that material features one-of-a-kind or incredibly rare glimpses into America's rolling western history. So, if you ever have an opportunity to attend one of these events, you can expect to see, hear, and experience plenty of details unavailable anywhere else.

Ultimately, the question about images got me to thinking about all of the pictorial stories in our archives. It occurred to me that it might be intriguing to explore more of the images in our writings. So, from time to time, I'll try to reach into the depths of the collection and pull out a few random images and/or particularly visual documents, sharing interesting elements and what we can glean from that part of our primary source research. No matter how many I retrieve for a post, we'll never get to the bottom of the pile but, hopefully, the visuals will inspire others to dig deeper into history, investigating what can be gleaned from every survivor of America's horse-drawn era and western frontier.

This week, let's look at three (3) elements from our horse-drawn past; a vehicle feature, an early wagon brand, and an accessory that may or may not be what it appears to be...

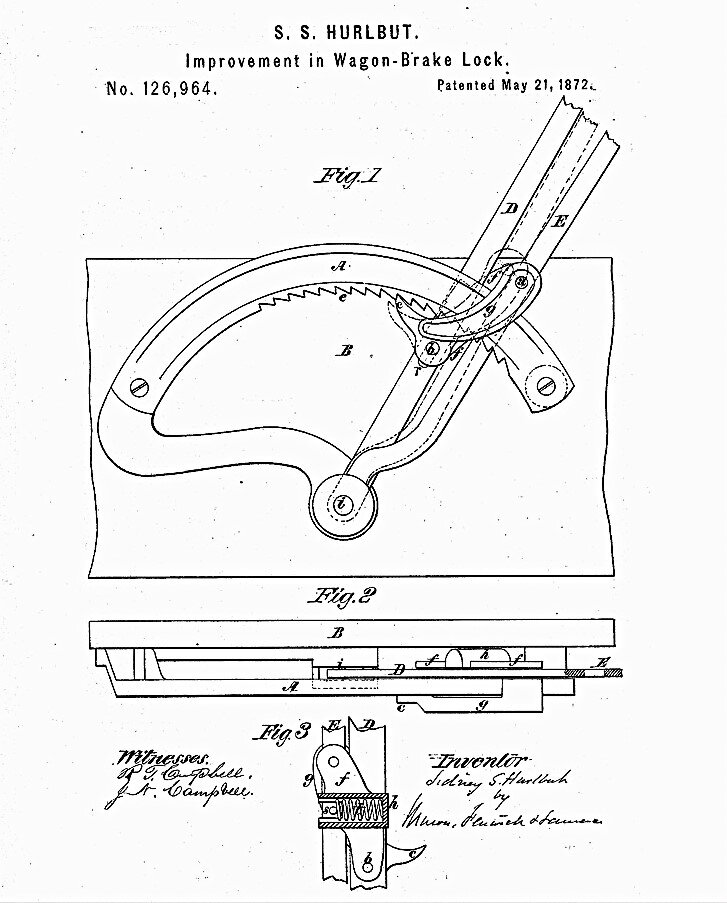

Hurlbut brake

The above section from an 1873 promotional card is easily one of the earliest, surviving advertisements for the Hurlbut wagon brake. The year before, in May of 1872, Sidney Hurlbut of Racine, Wisconsin was granted a patent on this brake rachet and lever. The advantage of the design was in the way the spring-operated pawl worked. The design helped lock the brake ratchet in a fixed position with optimum firmness and little likelihood of it popping loose until manually released. The idea was an extraordinary success and was in prevalent use for decades. In fact, it can still be seen on countless surviving wagons today. Because it is a two-lever, squeeze design and not a single rod-style lever, there are some who have questioned whether it was used on western wagons - as if single levers had a lock on the look of the Old West. Rest assured, from farm and freighting vehicles to chuck wagons, hacks, and business wagons, these ratchets were used throughout the American West during the 1870s, 80s, 90s and beyond.

Jackson wagons

Many wagon companies created a slogan to reinforce their vehicle's promotional appeal. Weber, for instance, used the expression, "King of All," while Peter Schuttler often used "The Old Reliable," and Mitchell was known to proclaim that they were the "Monarch of the Road." Some brands used multiple promotional titles during their history. The Jackson Wagon Company, which dated to 1837 and was a fierce competitor on the frontier, used the tagline, "The Common Sense Wagon." While the image below is cropped from the original, it still shows prominent advertising for Jackson on the front of an early carriage shop. This image is part of a larger cabinet card that clearly shows how the 'Common Sense' wagon was painted and designed in the early 1870s. The full image is not shown due to issues with theft that we've previously encountered. It's also why a great deal of the rarest material is reserved for our in-person presentations. Ultimately, this captured history helps us distinguish between authentic parts of yesterday and fabricated pieces. With sufficient amounts of these materials, the imagery - especially in conjunction with other promotional elements - can help provide a clearer picture of what was done by whom and when.

Screw Jack

One of the best ways to learn is to pay particular attention to things you've never seen before. Years ago, I came across a collection of what was referred to as Conestoga wagon jacks. All of the jacks were fairly close to the same size (roughly eighteen to twenty-four inches in non-deployed height - another foot to fifteen inches can be added to the total height when fully extended) but one was at least twice that measurement with a significantly longer shaft to lift or move things. It clearly stood out in the display.

While no specific documentation accompanied the Paul-Bunyan-sized jack, as it turns out, jacks like this were often used when felling and moving extremely large timber in difficult-to-reach places. In the 1870 photo shown below, the lumber jacks are literally 'jacking' the massive timber into a more accessible position for better access. These oversized screw jacks or jack screws may look like huge Conestoga jacks but they served a different purpose, allowing minimal effort to roll and better position large timber that would otherwise be hard to retrieve.

Another section of an image dating to 1870. This one shows screw jacks in use to move large logs.

As we travel farther away from an artifact's primary years of use, it becomes easier for that part of the past to lose its history and pertinence. Likewise, in the absence of information, it can be tempting to assume facts or attach best guesses based on modern-day evaluations. I've heard well-meaning but mistaken claims about certain elements on or around early wagons. Things like, "they didn't do that, they only did this, something else was never done," and so on. Without documented proof of the claims, the statements amount to personal beliefs, not necessarily facts. The problem with conjecture is that none of us were there during the nineteenth century when wooden wheels were rolling through the prairies, forests, mountains, rivers, deserts, and so forth. As a result, surviving imagery, writings, and other documentation that's undeniably tied to that timeframe is essential to helping us understand the who, what, where, when, why, and how's of the time periods.

Ultimately, these breadcrumbs left behind by our ancestors can provide a great feast of knowledge as well as plenty of humble pie should we get ahead of ourselves. The solid footing of unbiased primary sources, though, is incontestable and when it comes to the fading facts from old still frames, it's important to gather what we can while it still exists. Due to the fragile nature of this history, future generations will only have what we procure, protect, and preserve.

With a little effort, there's still a great deal to be found. When it comes to original images, whatever the format, from tintypes, daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and cabinet cards to carte-de-visites, glass slides, stereoviews, real photo post cards, illustrations, lithography stones, and even candid snap shots, there's a lot to be learned just by studying a world that's black and white.