As part of our continuing efforts to show the depth of America's first transportation industry, we've taken the last four weeks of our blogs and focused on three dozen questions. It's been an interesting journey, peering through a series of small windows into the vast number of topics related to early wagon makers. Today, we'll look at the answers to the final dozen questions, sharing insights into a subject that remains largely unexplored and still far too full of false impressions and speculation...

25) Wagons built in the U.S. between 1865 and 1895 changed very little in design.

While many tend to lump all wooden wagons into a single category of primitive uniformity, the truth is that there were many differences in these vehicles throughout history. The thirty-year period after America's Civil War saw countless changes in wagon building. In many ways, the war served as a catalyst of sorts; stirring innovative ideas, designs, functions, and features of these heavier transports. As a result, patent applications grew substantially following the Civil War. Vehicle companies took ownership of proprietary distinctions and intellectual properties, reinforcing those purported advantages in advertising, sales promotions, and even event marketing efforts.

26) Stencils for painting brand names on wagons were in use as early as the 1870's.

Prior to the 1880's, most builders of name-brand wagons were painting the striping and ornamental designs free-hand on their vehicles. Even as this 'personal touch' was taking place, the brand name, itself, was often applied with the aid of stencils.

27) The famous showman, P.T. Barnum, helped promote the Jackson Wagon Company.

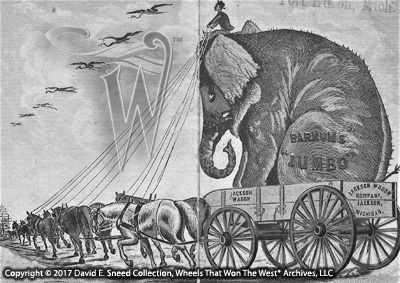

Absolutely true. This is another case of a firm within America's first transportation industry recognizing the power of celebrity and capitalizing on it. As the story goes,in 1882, P.T. Barnum finalized the purchase of Jumbo the elephant from the London zoo and wanted to ship him to America as a new addition to his circus. At the time, the elephant was promoted as the largest known animal in the world - nearing 7 tons. According to Mr. Barnum, due to the massive weight channeling through each of the elephant's legs, the city would not allow Jumbo to walk on the city streets. To get around the obstacle, Barnum claims he wrote for and received a Jackson brand wagon with its new truss rod axle. Jumbo was loaded onto the wagon and moved to the steamship bound for America - purportedly with no trouble. Countless promotional flyers, catalogs, editorials, and other advertising recorded the event as the Jackson firm made the most of Barnum's endorsement for years. As a side note, our common use of the word 'jumbo' can be traced to the name of this elephant.

|

| This rare flyer illustrating 'Jumbo' the elephant in a Jackson wagon was produced by the company to help promote the strength of their truss axle wagon. |

28) The Luedinghaus Wagon Company used a peacock as a brand icon.

While Luedinghaus wagons were made in St. Louis, it was another firm in that city that used a peacock for its brand icon - That being the Linstroth Wagon Company.

29) No wagon companies in America were building large freight wagons after 1900.

Au Contraire. This statement is also false. Many of America's best known wagon builders were still producing huge freight wagons during the first decade of the twentieth century.

30) The first Chevrolet and Buick vehicles built in the U.S. were manufactured in the buildings where Flint brand wagons had previously been made.

Sharing the history of America's first transportation industry has long been a passion of mine. So, when we came upon an opportunity to add a transitional piece to our collection, I jumped on it. In this case, the 'transitional' piece I'm referring to is one of the last Flint brand wagons built in the same factory that America's first Chevys and Buicks were built in.

31) The term 'dead-axle' wagon refers to a vehicle with a weakened axle.

This is false. 'Dead-axle' refers to an animal-drawn vehicle that does not utilize springs or thorough-braces. Some early, colloquial mentions of this term actually shortened it to the phrase 'dead-ax'.

32) International Harvester revolutionized the wagon industry with the first swiveling reach patent applied for in 1919.

Even though IHC widely touted their patented swivel reach in the late teens and throughout the 1920's, the concept had received multiple patents during the half century prior to IHC's design improvement.

33) The Lindsey Wagon Company in Laurel, Mississippi was the only U.S. builder of eight-wheel logging wagons.

While Lindsey is certainly one of the best-known builders of eight-wheel logging wagons, they were far from being the only manufacturer of these designs.

34) Harrington Manufacturing Company of Peoria, Illinois was a significant manufacturer of Rural Mail wagons.

Rural Free Delivery (RFD) mail wagons became a common site on America's backroads and more scenic routes after 1890. Numerous builders focused their efforts on the manufacture of these vehicles. They were especially designed for hauling mail along rugged, unimproved roads as well as throughout notoriously unpredictable weather. Among the many notable brands concentrating on this trade was the Harrington Manufacturing Company of Peoria, Illinois.

35) Using prison labor to manufacture wagons was seldom done in the 1800's.

On the contrary, there were a number of wagon makers (and other industries as well) that made significant use of prison labor in the 1800's. The practice was decried by builders using labor from traditional markets. Why? Because, prison labor was extremely inexpensive compared to the costs required to hire workers in the free market. As a result, the scales of competitive price advantage were often tipped in the favor of those using prison labor. It was a practice that, ultimately, was overturned through legislative action. A large percentage of those that had been successful in building wagons with prison labor were not able to compete when forced to hire outside the walls of confinement.

36) Fires, while feared, were seldom experienced by wagon makers.

This is a grossly false statement. Early wagon and carriage makers were plagued by fire. Wood frame structures, seasoned wood parts, flammable solvents, live coals, open flames/sparks, oil-stained floors, and greasy rags often conspired to generate the ultimate disaster. The problems were so rampant that monthly trade publications regularly published the massive losses and associated challenges for individual makers and the industry as a whole.

The last few weeks have been full of diverse topics as we've taken a little different tact to help highlight the vastness of the subject we're researching. Along the way, we've worked to include details on several different styles of vehicles as well. As we continue sharing all-but-lost details from America's wood-wheeled past, we're working on even more stories and have a great deal more to unveil in the coming months. Stay tuned. There's a lot on the horizon.

FYI... If you haven't signed up for notifications of anytime we update our Blog and other segments of the Wheels That Won The West® website, it's quick and easy. Just click on the link in the upper right of the website and enter your email address.

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC