America's first transportation industry included more than a million different variations and sizes of vehicles. If that sounds a bit far-fetched, consider the fact that, at one time, Studebaker claimed to have offered over 500 different sizes and configurations of farm wagons alone! Add to that the fact that most of the tens of thousands of known vehicle builders had their own way of doing things with every vehicle they made and it's easy to see how the math can quickly add up over a couple of centuries. Overall, it's just part of the reason that any serious study of America's early vehicles can be challenging at best.

Among the diversity of wheels used in the Old West were a host of city transports. Drays, grocery wagons, business wagons, carts, beer wagons, ladder wagons, police vehicles, and an entire host of other specialized designs not only dominated the eastern cities but also quickly made their way west. Among the custom creations used was a special configuration for city transit and hotel hospitality. It was referred to as the Omnibus.

Don Berkebile in his book, Carriage Terminology: An Historical Dictionary, defines an omnibus as a "public street vehicle intended to carry a large number of persons." He further outlined features including longitudinal seats, paneled sides, and a rear door allowing easy ingress and egress. Ultimately, it's a vehicle purpose and basic design need that's still in use today. In fact, it's where we get the term 'bus' to begin with.

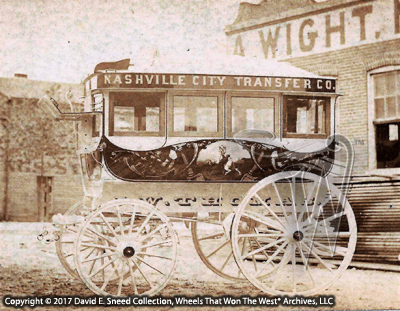

|

| This extremely rare, original manufacturer photo shows an omnibus built by Andrew Wight. It's another example of the kind of scarce history preserved in the Wheels That Won The West® Archives. |

Often graced with elaborate lettering and ornamentation, these large, early 'buses' were built in different sizes. Many were designed for around a dozen passengers while, perhaps, the largest one in America measured thirty-six feet long and was reported to have a capacity of 120 passengers (talk about a stretch limo!) Some double-decker omnibuses were also used in the U.S. but even more so in England. Another note of interest is that advertising messages for businesses eventually found their way onto many of these vehicles - just as buses and city cabs still incorporate today. Again and again, we see how much our modern society has been affected by ideas and designs originally drawn by horses.

So, where did the concept for an omnibus come from? The August 1895 issue of The Hub - picking up an article from London-based Cornhill Magazine - indicates that this style of vehicle had its origins with the French...

The 'germ' of the omnibus was of course an old one,and was to be found in the various 'stages,' coaches and diligences, where a number of persons were conveyed long distances in one common vehicle. Mr. Charles Knight, indeed, recalls some experiments made in the year 1800, when a lumbering vehicle running on six wheels and drawn by four horses was plying in London for short distances, but was not very successful. An old Irish reminiscent also 'minded the time' when a stage of similar character, on eight wheels, worked in 1792 between Dublin and Seapoint, a suburb about four miles off. There was here a boarding-house or hotel of some fashion, where Charles Matthews was fond of staying. The truth is, however, that we owe the invention to our so-called 'lively neighbors.' A retired officer named Baudry, living at Nantes, had established baths at Richebourg, which, he found, were patronized not so extensively as he desired. He accordingly, in 1827,started a sort of general car to transport his customers, which plied between the baths and the center of town. Baudry, later, set up his vehicle at Bordeaux and also at Paris; but as in so many other cases where the community is benefited, the invention flourished, though at the expense of the inventor.

In 1829 forage was dear, the roads bad; theundertaking ruined the luckless Baudry, who is said to have died of disappointment. It was in this year that the enterprising undertaker sent out the first London 'bus, which, according to a now defunct Dublin newspaper, Saunders' Newsletter, "excited considerable notice, from the novel form of the carriage and the elegant manner in which it is fitted out. We apprehend it would be almost impossible to make it overturn, owing to the great width. It is drawn by three beautiful bays abreast, after the French fashion. It is a handsome machine." It then describes how "the new vehicle, called the omnibus, commenced running this morning from Paddington to the city." It started from the "Yorkshire Stingo," and carried twenty-two passengers inside, at a charge of a shilling or six-pence, according to the distance. To carry eleven passengers on each side it must have been nearly double the length of the present form of vehicle, and of the size and appearance of one of the large three-horse Metropolitan Railway 'busses. An odd feature of the arrangement was that the day's newspaper was supplied for the convenience of the passengers...

According to John H. White, Jr. in his 2013 book entitled, Wet Britches and Muddy Boots: A History of Travel in Victorian America, the first use of omnibuses in the U.S. can be traced to New York City. While there were a number of American builders of these vehicles, the most prominent is likely to have been John Stephenson, also located in NYC. Stephenson is not only the builder of the massive, thirty-six-foot omnibus mentioned above but his firm is estimated to have constructed over 25,000 streetcars and countless horse-drawn vehicles in its roughly 85-year history. The firm found its niche in 1832 with the construction of a streetcar for John Mason, a well-known banker and merchant. The design included numerous features making it easier and more stable to use. It was an instant hit with the owner and the public. The rewards didn't stop with simple accolades. On April 22, 1833, Stephenson was granted a patent for the design - America's first streetcar (tram) on rails. Even so, his innovations didn't stop there. For the next half century, he was granted numerous patents for streetcar designs. One of the most detailed histories on Mr. Stephenson can be found in the online archives of the Mid-Continent Railway Museum in North Freedom, Wisconsin.

Andrew Wight was another notable builder of omnibuses as well as street cars, express, business, and freight wagons, and also circus wagons and cages. Wight had been an ornamental painter for John Stephenson's legendary firm in New York and, likewise, held horse-drawn vehicle patents. In 1858, Wight had the itch to move west, settling in St. Louis and opening his own vehicle manufactory. By 1874, he provided work for 100 employees with street cars sold throughout the West and omnibuses permeating the Mississippi Valley region.

|

| This image shows a portion of an early advertising card used by Andrew Wight. It's also housed in the Wheels That Won The West® Archives. |

Another organization involved in the creation of omnibuses was located in Cortland, New York. The company was founded in 1881 by W.T. Smith, originally of Homer, NY. Afte rthree decades of carriage-building and manufacturing omnibuses for roughly a half dozen years, Smith found himself enticed to move to Cortland. Once there, he entered into a co-partnership with the Cortland Wagon Company to form the Cortland Omnibus Company. Within a decade, the firm was building as many as 175 omnibuses per year and shipping them all over the U.S. During this time, the vehicles ranged in price from $300 to $500 each.

|

| Courtesy of the Long Island Museum of American Art, History, and Carriages, this photo shows another type of omnibus design. The 'Grace Darling' was used in the New England region for a variety of excursions and event transportation needs. |

This blog, in no way, is meant to be a detailed study of omnibuses. There is a great deal more to the story of these vehicles, including the early design evolution from 'Sociables' and 'Accomodations' as well as a myriad of builders, industry as a whole, and the vehicle's transition into today's bus configurations. Ultimately, my intent here has been to help shed some light on other vehicle types and their contribution to municipalities and businesses all over the country - including the West.

Just as nineteenth century resorts and hotels used horse-drawn omnibuses to transport passengers to and from the train depot, many hotels still use a 'bus' to pick folks up from the depot (i.e.airport terminals). Similarly, municipalities also continue their use of modern-day buses for both intercity and intracity transportation. Times may have changed but transportation needs will always be a priority; the result being that many ideas started in the horse-drawn era remain as an equally important part of modern society.

|

| Horse-drawn omnibuses were a common sight on America's well-populated streets in the 1800's and early 1900's. In many cities, they numbered in the hundreds. |

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC