|

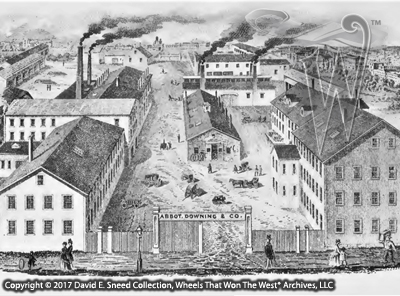

| Abbot-Downing was one of the few U.S. vehicle makers located in the East that successfully competed for business in the American West. |

When it comes to our own research breakthroughs, there are special moments that tend to stand out, such as our exclusive uncovering of multiple patents on sheep camp wagons... the finding of a pair of very few known photos of a McMaster Camping Car... the incredible, forgotten-attic rescue of thirteen lost letters from renowned wagon maker, Joseph Murphy in St. Louis - four of which were written by Murphy, himself... acquiring and documenting primary source records for legendary vehicle builders like Hiram Young and Lewis Jones as well as freighters F.X. Aubry and Alexander Majors... or even the surprise of coming across the earliest surviving production-built Studebaker wagon. Those and so many more significant finds have been continual, real-world-reminders of the rewards of perseverance. None of the discoveries were possible, though, without first believing that there is still more history waiting to be rescued.

In the midst of so much time spent chasing down leads, we've recently been fortunate to help restore even more background to one of the most legendary parts of America's stage-coaching past. Before we dive into the story, though, I want to give significant credit to well-known Concord Coach historian, Ken Wheeling, for his invaluable contributions. Perhaps no other modern-day source has devoted so much time to researching Abbot-Downing and their Concord Coaches as Mr. Wheeling.

A few weeks ago, I'd written an update of sorts to a mystery stagecoach photo I had come across. The photo started us down a road with a number of diverging trails that had to be studied. Like so many other obscure stories we've chased, the journey to connect the dots and track down pertinent elements has been an extraordinary venture. This particular mission started roughly a year ago. At the time, I had been working on content for a blog. In the course of those events, I picked up a large, antique book in our archives and began thumbing through it. The tome was a huge, four-inch-thick, 18-plus-pound, hardbound volume of The Carriage Monthly. It held countless issues of the trade publication dating to the late 1890's. As I slowly worked my way through the aged content, I came to page 120 of the July 1899 issue. That's where I stopped. There, near the top left-hand column was the image of an old stagecoach. The photo was poorly reproduced but my intrigue was piqued. Centering the body of the coach were style lines that seemed different from what I was accustomed to. The photo was accompanied by a caption and brief write-up. I didn't realize it at first but, the article was a slight diversion. While the text credited the coach to Abbot-Downing, the provenance of the vehicle didn't line up with any of the supportable leads we were able to uncover. It was a bit confusing in the beginning but, as I looked closer, I realized that the last sentence in the account noted the photo to be a "representation" of the coach described in the story. Clearly, the editor had an article to publish and needed a photo of an old stagecoach to accompany it. Apparently, this one was close at hand as a literal connection didn't exist between the story and the photo. Yet, the image stuck with me.

As I shared earlier, what really caught my attention were the uniquely-spaced body rails on the coach. As it turns out, it's a feature that's been helpful in tracking the history of this piece. After the initial discovery of the image in The Carriage Monthly, we set out to see if we could find any other coaches with these wider body rails. Piece by piece, over the next few months, we came across another handful of photos showing what appeared to be the same coach. Every one of these early photos were taken in the Montana region of Yellowstone Park. We reached out to a few folks but, we just didn't have enough clues to put things together in a way that made historical sense. Then, as Forrest Gump might say, the answers came right out of the "blue clear sky." The acceleration of events took place while I was looking for additional coach imagery. Clicking through a tedious collection of web pages, I found myself looking at an on-line auction highlighting a photo from Abbot-Downing. It showcased an old coach. It looked familiar. Was it? No, it couldn't... Wait, that's the... that looks like the... is that the same coach? My heart raced as I headed back to the old book of The Carriage Monthly publications. Looking again at the photo, there was no doubt about it; the two images weren't just showing the same vehicle. The original cabinet card in the auction was the exact same photo in the magazine! The only difference was that the magazine had cut the coach out of the photo background. Almost one hundred twenty years after being published in the old trade paper, the image had resurfaced. It was in California.

I was determined to purchase this historic piece and felt like a kid at Christmas waiting for it to arrive in Arkansas. Once here, we had more clues to follow and the stories this artifact unfolded were extraordinary. As I'd mentioned in one of my previous blogs, the stagecoach in the photo had a large framed print hanging from it that will be familiar to stagecoach enthusiasts. It's the well-known image of a very famous trainload of coaches shipped in 1868. Hmmm, this cabinet card also says this coach was built in 1868 - in Concord, NH. In total, the provenance attached to the front and back of the card is full of intrigue and plenty of frontier drama.

While I was able to track the whereabouts of the coach up through the 1920's, Ken Wheeling and his files picked up the story from there. Ultimately, Mr. Wheeling's files helped point us to a specific coach number. From there, the 20th and 21st century trail became considerably clearer. Again, thanks to Ken, we now have a more defined view of this coach. Even so, the provenance may still be a little fuzzy. We'll get to more of that later.

We've come to believe that the photo we uncovered is the earliest surviving image of Concord Coach #259 - the only exception being the panoramic image taken at the time of shipping. The cabinet card is authoritatively dated to 1897 with the subsequent printing in The Carriage Monthly in 1899. Even so, it's quite likely that the photo, itself, dates to 1893 - the year of the Columbian Exposition or World's Fair in Chicago. As we've mentioned before, the old photo appears to have been taken in an exhibit setting and the provenance provided by Abbot-Downing indicates the coach was shown at the Exposition.

According to additional records supplied by Ken Wheeling, the coach had multiple owners during its western career. One group of owners, George Wakefield & Charles Hoffman (W & H), operated a mail line and passenger service in Yellowstone from 1883-1891. Later images show the coach on display in Yellowstone during the 1920's. Faded W & H lettering can still be seen on the doors in those photos. Initially, though, #259 was one of a number of stages ordered by Wells Fargo for frontier service. In fact, there were a total of forty of these coaches purchased from Abbot & Downing and shipped to Wells Fargo destinations between 1867 and 1868. Thirty of them went out in one shipment in 1868. In that load, #259 was joined by twenty-nine others - all placed onto one long line of flatcars - and hauled to Omaha, Nebraska.

Mr. Wheeling shared that the original order from Wells Fargo in 1867 was for only ten coaches. However, over a period of several months, the order was updated, with various elements within the purchase being adjusted. The end result was that not only did Wells Fargo receive those first ten but the group of thirty as well. As it turns out, those two and a half dozen coaches shipped in April of 1868 were the largest, single shipment of Concords ever made by Abbot-Downing. Regrettably, very few of these are still in existence. More to the point, #259 is one of only three that have survived from the thirty shipped.

Looking past the coach number for just a bit, we've been told that some feel only part of the surviving coach is actually the true #259 related to Abbot Downing. For any researcher, it's a suggestion that requires deliberate and careful study. The challenge, it seems, comes back to a few variances in the body - including those exterior style lines I'd mentioned. As I'd shared, they are a bit different than most surviving western Concords built by A-D and it, naturally, leaves us to question why. According to Ken Wheeling, additional questions have dogged this coach. An early restoration team noting some extra mounting holes, wondered whether the jump seat with the #259 reference actually belonged to this coach from the beginning. These questions have caused some to speculate that this stage might have been built by another firm such as Gilbert & Eaton of Troy, New York with the jump seat replaced by one from Abbot-Downing. While it's an interesting theory, unfortunately, no direct records have ever been found that would support the thought. In stark contrast to the speculations above, the original Abbot-Downing cabinet card we came across is quite blunt in its proclamations. Clearly, during the 1890's, the coachmakers at Abbot-Downing had no problem in not only identifying this exact coach as one of their own but went multiple steps further by photographing and promoting the coach (even using a well-known photography studio from Concord, NH).

After photographing the vehicle, they produced and distributed the cabinet card. Along the way, they also engaged in the procurement and printing of historical research that highlights the western history of the coach. Some of the provenance describes harrowing experiences the stage was involved in, where and what routes it ran, dignitaries that rode in it, and numerous other details. In truth, that's a lot of work for a reputable firm to go through if they weren't 100% sure of the coach's identity. Plus, the old firm apparently hung a photo from the coach that showcased the famous trainload of Concords. As an additional side note, Ken Wheeling's files show that Edwin Burgum, the son of John Burgum, well-known painter/illustrator at A-D, saw the coach at Mammoth Hot Spring in Yellowstone during the 1930's and also identified it as A-D's #259.

Today, coach #259 is part of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, otherwise known as the Gateway Arch Museum in St. Louis. Unfortunately, as of this writing, the historic transport is in storage as there's a fair amount of renovation going on in the museum. Officials in St. Louis told me they hope to have the facility re-opened and the Concord back on display sometime in 2018. As it happens, that will be the 150th Anniversary of #259's creation and shipment into the West for Wells Fargo. In recognition of the upcoming anniversary and the exclusive nature of this image, we haven't published a photo of the card in this blog. It seems more appropriate to determine if the Gateway Arch Museum may want to include it within their re-opening plans.

It's been an interesting historical chase and, for now, I'm satisfied with the information we've gathered. I will offer one teaser... there is additional provenance on this card that has led us to more history and, even more published reporting, on this coach. As is often the case, every lead has the potential to help add to the story of a particular set of wheels. For the moment, though, there are other irons in the fire as well. So, we'll turn our focus back to other projects and see what else we can dig up. Speaking of our research, someone once asked me, "How do you find all these pieces?" It's an understandable question and the answer is a lot easier than the actual process of discovery. Here's the secret... I look and look and look and look and look and look. In other words, the searches we engage are not casual affairs of curiosity. Nor are they limited to one or two areas of infrequent exploration. Our efforts are constant. There's a vigilance and tenacity attached to the pursuits. Even so, the majority of our investigations do not produce quick or necessarily even newsworthy results. Most searches do, though, tend to move us closer to our subjects. More often than not, the biggest findings come under the guise of a vague clue, a clearer understanding of something, half of an answer to one of our own questions, or simply another fractional-step toward a previously unknown lead. Ultimately, every particle of information we come across is another building block that future research can benefit from.

Through it all, we've been blessed to play a role in a number of incredible finds. While this latest search resulted in the acquisition of amazing provenance to an ultra-rare coach once owned by Wells Fargo, it's far from being the final piece of history we hope to help rescue.

By the way, if you'd like more details on the story of Abbot-Downing's shipment of the thirty coaches in 1868, see the article by Ken Wheeling in the October 2002 issue of The Carriage Journal.

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC