As I stood in the middle of the strangely quiet and virtually abandoned city block, for a moment I could imagine the sights and sounds of old growth timber being sawn. At my feet, shavings from a draw knife lay on the ground. Swept into a pile near a dusty stairwell, the wood flakes served notice that someone would be returning to finish the job. The sound of hammers and anvils rang out while molten metal fireworks showered a dirt floor.

Around the corner, workers stacked lumber in sheds to dry and complete the seasoning process. At the back of the lot, a clerk inspected a supply of custom-fabricated parts. Nearby, a painter lifted his brush and stepped back from his work. Wiping his brow, he surveyed deep blue pinstripes freshly laid on the wooden wheel. His craft was a specialized form of commercial art; his canvas could literally travel the world.

Out front, horse-drawn street cars, wagons and carriages filled the north-south thoroughfare. My eyes fixed on a large, low-slung dray rumbling south toward the riverfront levee and docks. As it passed by, I looked up to see workers wheeling two of their latest creations out the door.

Captivated by the vision, I could feel my daydream settling in. But before I could picture anything else, the ground began to shake, followed by a rush of wind and the growl of an engine brake on a passing tractor-trailer rig. It was enough to jolt me back to reality, but I remained intensely curious as to what this area once looked like. I was on the grounds of what was once a thriving wagon manufactory in St. Louis, the “Gateway to the West.”

At the time I first wrote this article, the property was part of a recently completed archaeological dig conducted by the Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT). Numerous excavation holes and trenches permeated the site, exposing 19th century limestone foundations. Remnants of brick forges dotted the terrain with significant samples of the last coal used. The dig also uncovered early millstones (used to grind paint), slate roofing materials, heavily corroded metal wagon parts, water closets, cisterns, and countless handmade bricks. As a historian of the early American transportation industry, I’m accustomed to the challenges of exploring the mostly forgotten pieces of our past. Usually, I’m the one doing the searching. This time, the story came looking for me.

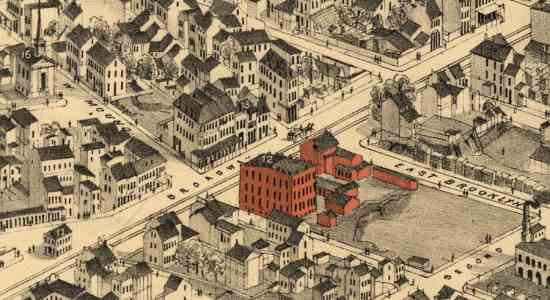

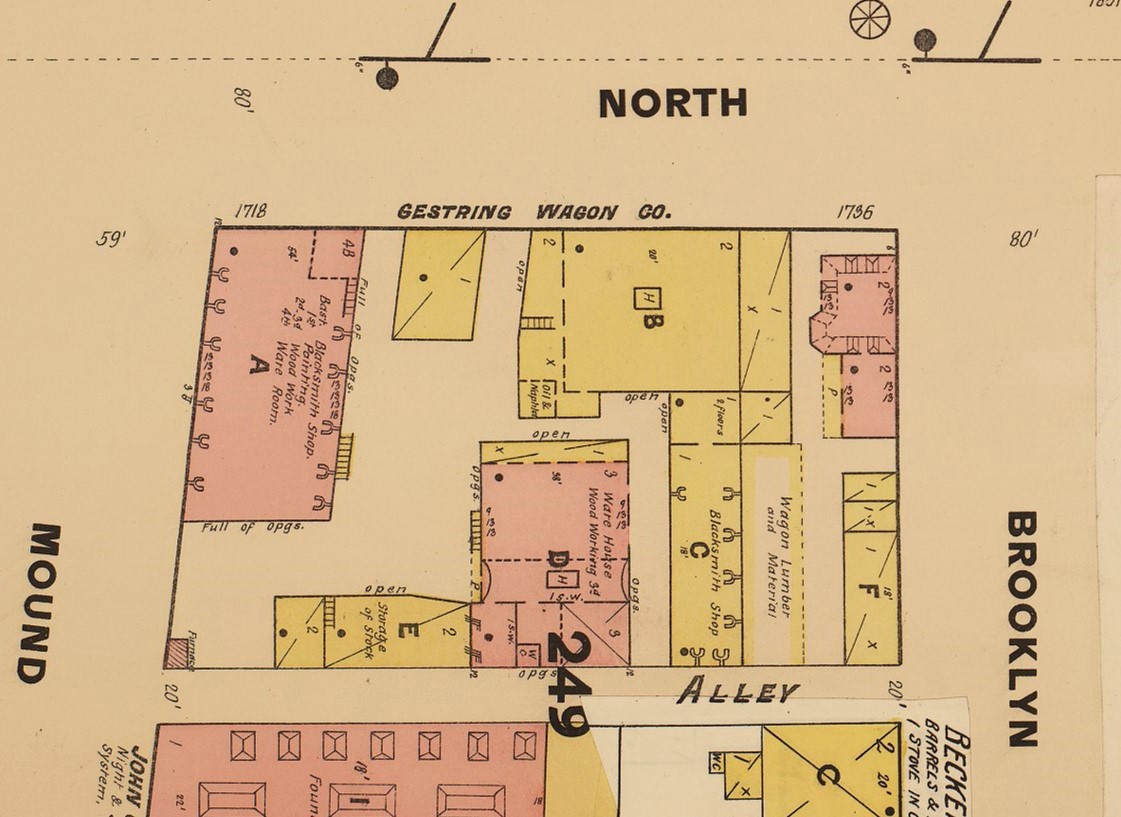

The early illustration above (in red) provides additional insights on the layout of the Gestring Wagon Company. Image Courtesy Wheels That Won The West® Archives.

Above is an 1897 view of a portion of the Gestring Wagon Company grounds. The image is cropped but the uppermost part of this image shows North Broadway Street bordering the western edge of the factory. Just a short walk to the east is the Mississippi River.

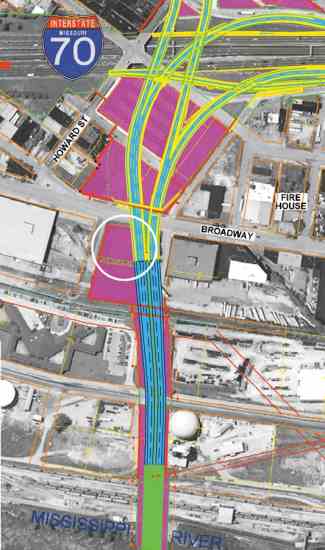

The circled area in the image above is where the old Gestring factory was located and how that area now intersects with Interstate 70 and the new bridge over the Mississippi River. Image Courtesy of MoDOT.

Digging For Answers

In December 2009, I received a call from the MoDOT archaeological staff seeking information and materials related to a dig near Broadway, Mound, and Brooklyn streets in St. Louis. The state had acquired the property as part of a Mississippi River bridge construction project (Stan Musial Veterans Memorial Bridge). MoDOT’s historic preservation group was researching, excavating, and cataloging what remained of several 1800s-era businesses that had operated near the site.

Limestone foundations as well as brick forges, cisterns, and even early 'water closets' held leftover artifacts from the Gestring Wagon Company in St. Louis. The images above show MoDOT archaeologists working on the site. Related dig images Courtesy of MoDOT.

Among those of specific interest was the Gestring Wagon Co. (pronounced guess-string), established in the 1850s. Although the company’s original buildings were razed years ago, the firm is historically significant for a number of reasons, including the fact that the Gestring earthworks had remained largely undisturbed since the company ceased operations midway through the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Equally notable, this horse-drawn vehicle company not only survived the transition into the automobile era, but also outlived many prominent early wagon makers. It’s an especially remarkable achievement since, in more than 75 years of operation, the company never adopted steam power or other tools of mass production employed by so many other vehicle builders. Every Gestring wagon was handcrafted by trained artisans who carried on the same basic construction principles of the earliest American wagon makers.

A Gestring brand wagon we found at the Santa Ynez Valley Historical Museum & Parks-Janeway Carriage House in California. Image Copyright © David E. Sneed, All Rights Reserved.

Building A Legend On Wheels

Established during the mid-to-late 1850s by Casper Gestring, the company had a German heritage. As a young man in Prussia, Gestring heard of opportunities in America and set his sights on the New World. His voyage across the Atlantic was the first test of his convictions since the grueling journey lasted 13 weeks.

As a young man in his 20s, Gestring soon found his way to St. Louis where he worked as a blacksmith. In a shop on the northeast corner of Broadway and Brooklyn, he shod horses for the Union Army while also engaging in traditional repair and fabrication work. With steady business and a family to support, it wasn’t long before Gestring added wagon-making to his list of products and services. In fact, according to a 1935 New York Times interview with grandson Henry Gestring, the firm was busy building wagons for the Union Army during the Civil War.

By 1865, city records show Gestring operating under the name Gestring & Co. Henry Luedinghaus, Gestring’s first partner, was destined to make his own mark in the wagon trade. Not only would his namesake brand become known as a major wagon manufacturer, even branching into production of motor trucks, but Luedinghaus eventually merged with another legendary St. Louis maker: the Espenshied Wagon Co.

With each partner holding strong ambitions and staunch business opinions, the alliance between Gestring and Luedinghaus was short-lived. By 1866, the two parted ways. Gestring left his original blacksmith shop and moved across the street to the southeast corner of Broadway and Brooklyn, taking on Henry Becker as his associate. The new company, Gestring & Becker, got off to a solid start. The partnership lasted about 15 years, into the early 1880s.

Ancient Remains

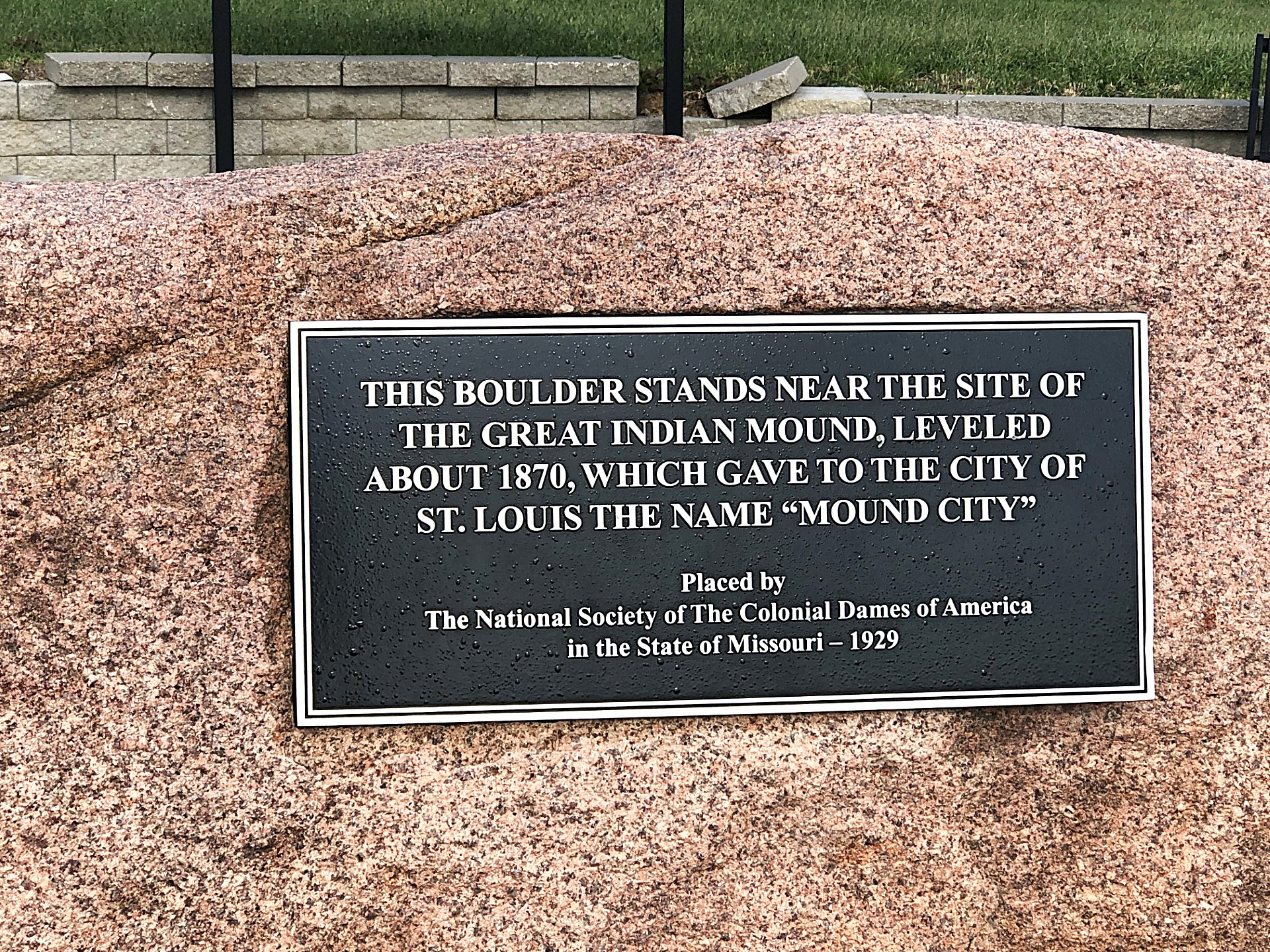

According to oral histories passed down in the Gestring family, part of a huge American Indian mound was removed before the factory expanded over the new Broadway property. The mound covering the area was the largest in the city, measuring 319 by 158 feet and 34 feet tall, comparable to a three-story building covering close to the same area as an NFL football field.

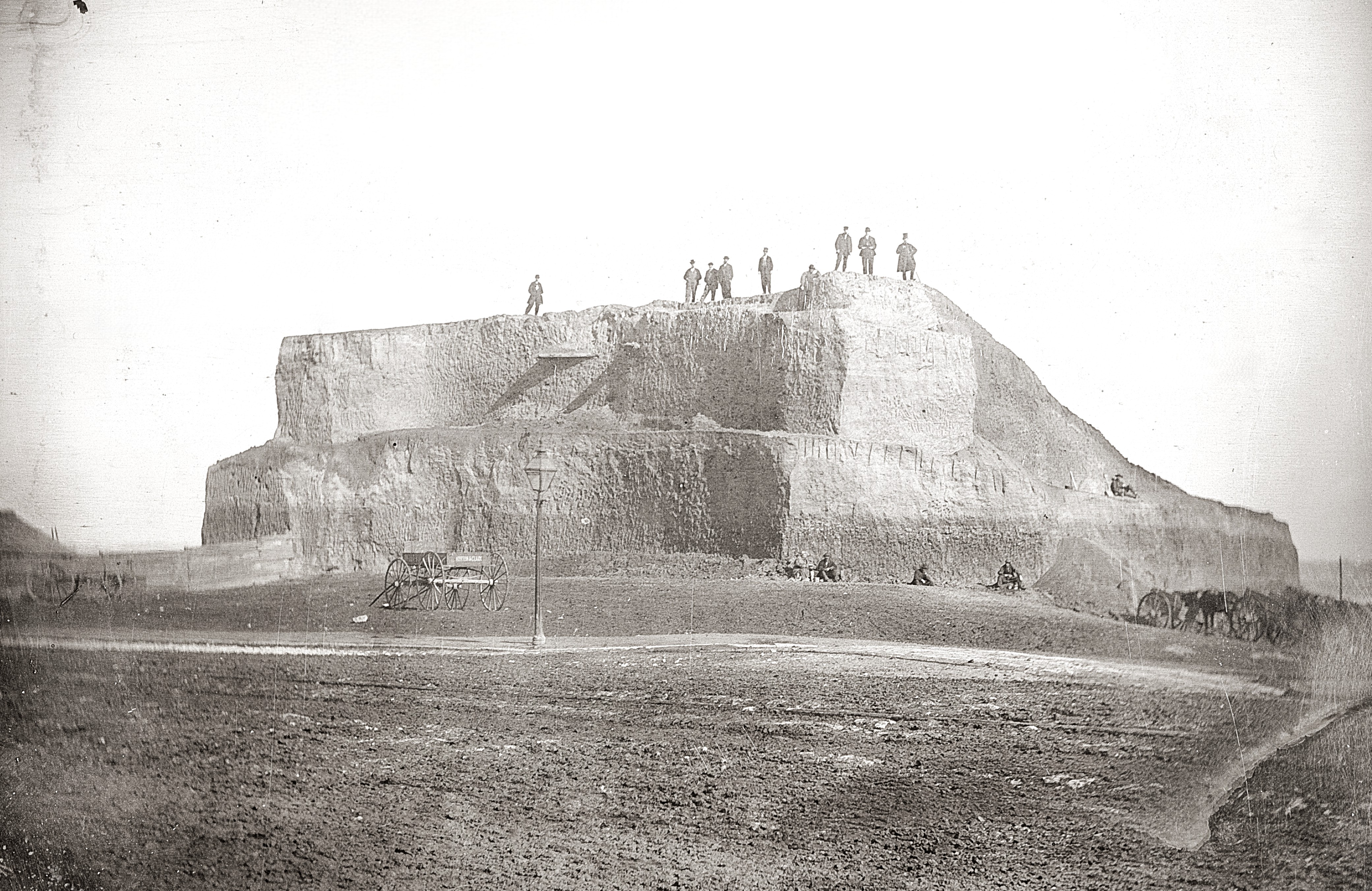

Because the mound was a significant Native American landmark, the act of dismantling it generated a fair amount of interest. The massive earth works are estimated to have been built between 700 and 1400 A.D. by the Cahokia Indians for burial and ceremonial purposes. The large number of such mounds in 19th century St. Louis prompted the city’s nickname, “MoundCity.” Thomas Easterly, a daguerreotype photographer of the era, captured images of some of the early mounds as well as the final leveling of this particular “Big Mound” in 1869.

A view showing the dismantling of the 'Big Mound' near where the Gestring Wagon Company was eventually located. This image was taken in the late 1860s. Image Courtesy of Wiki Commons and the Missouri Historical Society.

Immediately above is another pair of views taken by Thomas Easterly. These show the remaining portions of the "Big Mound" as it appeared when looking east from Fifth (Broadway) and Mound Streets. Images Courtesy of Wiki Commons and the Missouri Historical Society.

By 1875, on the eve of America’s centennial celebration, Gestring’s business had grown far beyond his humble blacksmith beginnings. The company stretched over the entire half-block bordered by Broadway, Mound, and Brooklyn streets. The factory was housed in a large, three-story brick structure with blacksmithing in the basement. Upper floors were used primarily for painting and woodworking. An additional multi-story building on the back of the property was used for extra woodworking projects and storage. Otherstructures on the site supported additional blacksmith work and lumber storage. Gestring also owned property on Broadway, just north of the main operations. Most of the facilities on that land housed lumberyards and blacksmith works.

Surrounded by churches, schools, planing mills, a chair factory, food market, stove works, and marble company, the Gestring brand took shape within sight of legendary wagon makers Weber & Damme and John Luking.His former partner, Henry Luedinghaus, had a large factory across the street, and the highly acclaimed Joseph Murphy Wagon Works was just a few blocks south.

Keeping Quality First, The Old-Fashioned Way

Competition between vehicle makers often highlighted their distinctly unique innovations. In 1878, Gestring collaborated with James Fullerton, also from St. Louis, and won a patent for an improved axle skein.That design feature remained an integral part of Gestring products well into the 20th century, yet another indication of the company’s commitment to quality, innovation and aggressive competition. The commitment to quality did not slow production. Gestring production numbers in the 1880s matched and often exceeded the work of other St. Louis wagon makers. In fact, Gestring’s 1882 output was valued in excess of $100,000 – more than the total combined output of key St. Louis makers like Joseph Murphy and Louis Espenschied for the same general timeframe.

While the numbers aren’t comparable to those of large-scale makers like Studebaker, Bain, or Peter Schuttler, they remain significant for mid-sized firms. Luedinghaus, Weber & Damme, and Gestring all vied for government wagon contracts in the 1880s, going head-to-head with the huge factories of Moline, Alexander Caldwell (Kansas), Studebaker Bros., and Austin,Tomlinson and Webster.

While mechanization and steam power offered the opportunity to increase production, it was an area that consistently separated Gestring from many other makers. Throughout the company’s history, the Gestrings remained convinced that quality was synonymous with personal attention to detail in totally handcrafted vehicles. It was a determination that kept costs manageable and orders consistent, even in slow economic times.

Original coal salvaged from the factory forges of the Gestring Wagon Company. This type of historical search and rescue has come to define the Wheels That Won The West® Archives. Image Copyright © David E. Sneed, All Rights Reserved.

This handpainted logo is on a Gestring wagon in the Wheels That Won The West® collection. While the base color of the wagon appears to be white, the sun and time has chalked the original color, which was a creme-tone. This wagon will date to the 1870s and includes box brakes and a hook for the lock chain. Image Copyright © David E. Sneed, All Rights Reserved.

In the early 1890s, St. Louis, like most of the rest of the country, was riding a wave of economic optimism. Gestring continued to expand his operation. The good times were about to come crashing down, though, as railroad and bank failures throughout the decade created financial instabilities, hampering economic progress for the majority of the country.

When Casper Gestring died in 1903, he left a legacy of a prosperous, well-managed business. His family picked up the mantle of personalized quality and carried it well into the new century. Production continued at full capacity. By 1909, the company’s workforce of 60 produced about 1,500 vehicles a year. Gestring Wagon Co. ceased operations in 1935, but not before the founder’s great-grandson, William, would officially add his name as the fourth generation to build wood-wheeled wagons. As a boy of 7 or 8, William remembers his father overseeing him as he was allowed to stencil the Gestring name on the last handmade, factory-built wagon in America.

This promotional watch fob is among the surviving materials from Gestring's heydays. Image Copyright © David E. Sneed, All Rights Reserved.

Gestring Leaves Lasting Legacy of Leadership

One more time, I walked the old factory grounds, picked up a few mementoes and shot photos before the setting forever changed. There is a certain amount of irony in the fact that such a strong part of St. Louis’ past is now permanently covered by a new highway and bridge. The old factory sat within an easy walk to the banks of the Mississippi River. Workers there would have been accustomed to the shrill sound of steamboat whistles in the bustling river city. Now, a 21st century bridge will carry travelers on their way to new opportunities. Speeding over the site of so much history, how many will know or care about the roots of progress just beneath them?

As I mulled over those thoughts, the story unfolded in a new direction, culminating in a visit to Casper Gestring’s final resting place. On a prominent corner in St. John’s cemetery in St. Louis, the Gestring family plot is centered on a large, ornate marble obelisk. Markers nearby bear the names of many Gestring relatives and factory workers. It occurred to me that, even in death, these people shared a bond that the fast pace of mass production and instant gratification seems to have erased from today’s world.

Perhaps Casper Gestring had it right all along. Perhaps there is more to life than filling our days with so much that we struggle to carry the load. Even his wagons were stamped so users would know capacity limits. My eyes followed the lines of the obelisk, gradually moving upward, tracking carvings and corners until I stopped at the uppermost point of the oversized marker. Instantly, I was taken aback. I had been so preoccupied with the headstones and names that I’d overlooked an obvious living metaphor.

Centering the Gestring family cemetery plot, a large marker is shaded by a massive oak tree. It's a symbolic tribute to the hardwood heritage of this legendary wagon maker. Image Copyright © David E. Sneed, All Rights Reserved.

There, overshadowing the entire plot, was a giant oak tree standing like an aged sentinel. Hardwoods like that were the heart and soul of Gestring’s life and America’s early transportation history. This colossal memorial had spread its roots and pointed upward with an unfolded canopy. To all who take time to notice, it’s a tranquil and timeless tribute to the rewards of a time when hard work, quality and integrity weren’t just ad slogans, but a way of life.

Of the thousands of wagon makers that once existed in the U.S., only a few hundred are remembered today. Even fewer road-worthy products of those companies remain in existence. Almost none have been profiled through detailed excavation studies. So, why all the interest in Gestring? Beyond MoDOT's bridge project, the Gestring legacy highlights some of the most significant days of St. Louis’ transportation history. Furthermore, the company was large enough to do contract work for the U.S. military, and it stood shoulder-to-shoulder with leading competitors. Casper Gestring dared to blaze his own path, building every vehicle by hand, and outlasting almost all of his competitors. Gestring knew his strengths, set his course, and delivered a heritage and product that’s still making news more than 150 years since the firm's founding. It’s the same kind of commitment that built our nation and the hallmark presence of a St. Louis legend and Mound City maker. WTWTW