Levi Newton, the company founder and namesake, was born in 1810 in Darien, New York. As a young man, he apprenticed in the trades of cabinet and furniture making, developing a keen eye for detail while schooling his hands in the fine art of quality woodwork. His skills and business acumen eventually led him to open his own wagon shop in the small western New York community of Attica.

Like most early wagon-making operations, Newton’s facilities were humble but adequate. The local shop provided well for its immediate community and even had a certain amount of regional influence. Filled with the dry wood, paint, solvents and forges necessary for wagon building, it was also a tinderbox just waiting for an ill-conceived spark. As fate would have it, in 1854, the recipe for disaster was fully kindled when the entire firm was destroyed by fire. Like so many that had come before him and others that were destined to repeat the tragedy, the fire was a crossroads for Newton. Taking stock of his options, he didn’t dwell long on what to do. It seems that if “necessity is the mother of invention” it’s also a large part of the secret to entrepreneurial success. After a decade and a half in the business, Levi Newton knew the West was growing in importance and opportunity – so he picked up the pieces and traveled to Batavia, Illinois. It was a region that had been a good sales area for his wagons and, during the last half of the 19th century; it would also become known for its excellence in windmill production, stone quarries, farm implements and even the production of paper for metropolitan newspapers.

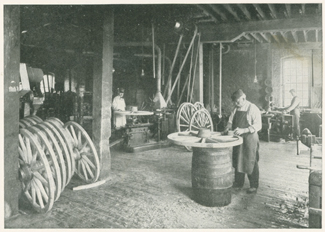

Newton quickly sized up the town and purchased a spot on the Fox River that would help provide power for his manufacturing machinery. Once the deal was struck, he immediately began excavating a raceway and water wheel pit. Beyond the challenges of new construction, though, Newton had another problem critical to his success in Batavia. He needed seasoned hardwoods for wheels and undercarriages as well as other select timber for wagon boxes. Without it, he couldn’t begin to make the first vehicle. As a competitor to other wagon makers, the local rivals weren’t about to share their supplies, but after a little searching, he found what he needed. Dry, stacked, and easy to access, it came in the form of an old log cabin. After purchasing the vintage structure, he dismantled it, turned some of the logs on a lathe, then bored and mortised them by hand to make wheel hubs. It was an important step forward that further reflected the hardened resolve of the 44 year old Newton.

That first year in Batavia he built 36 wagons and 35 buggies. It was a sign of more success to come as Batavia was growing and the entire country was bursting to ‘Go West.’ To put the timeframe in perspective, the recently formed Wells-Fargo Company was only 2 years old, the legendary King Ranch of Texas had just been established the year before and the first run of the renowned Butterfield Overland Mail Stage was still another 4 years away.

In 1857, to better reflect the addition of other members into the firm, the company name was changed from L.C. Newton & Co. to Newton and Company. Over the next half dozen years, Levi Newton and his son, Don Carlos or D.C., grew the output of the wagon works while also building up the increasingly sought-after Newton brand. By 1860 and the outbreak of the Civil War, the Newton shops employed 50 men and also included a foundry. Period accounts indicate that Newton wagons were a “familiar sight among the teamsters of the prairie and plains.” At the same time that Newton’s heavy wagons were receiving so much praise, he was being equally lauded for his lighter wagons and carriage work.

The 1870’s dawned with exceptional promise as the company continued to grow. In fact, by 1872, Newton was building an average of 1200 wagons and 250 carriages per year. Unfortunately, the momentum of hard work and a growing customer base was not enough to sustain itself. The wood frame factory was vulnerable and haunted by the merciless greed of an old nemesis. About 7 p.m. on the dark, winter evening of December 23rd, a foreboding wind had driven temperatures to a bitter 20 degrees below zero. With the spirit of Christmas in the air, most of the city’s residents warmed themselves around a stove or fireplace trying to forget about the brutal weather outside. While the home fires burned, other, more menacing flames were also at work, quickly consuming the factory’s woodshop. By the time sufficient help could arrive, the business was fully engulfed. The city had no fire-fighting equipment, but Newton did… a great asset, no doubt procured as a result of Newton’s earlier tragedy in 1854. Unfortunately, the wise investment was unwisely stored in one of the burning buildings. It was never used and the works were a total loss. Making a bad situation even worse, 1872 was the year after the Great Chicago Fire and insurance companies still had not recovered from their own staggering loses. As a result, Newton had to absorb the $40,000 devastation on his own. He teetered dangerously close to bankruptcy. Working with little more than his reputation, it took six months of iron-willed grit to restore the company. Then, on July 1, 1873, Newton brought additional partners into the firm and incorporated it as the Newton Wagon Company. The extra capital gave the business the financial strength it needed - and none too soon. Just one year later, the frustrations and hard times continued.

Positioned on the Fox River, Newton used water to power his saws, wood lathes, drills and other machinery. As long as the water flowed, everything worked well. But, in 1874, a lack of rainfall above the factory had shrunk the river well below the raceway for the waterwheel. Constant efforts to keep water flowing through the raceway diverted much of the factory’s time from manufacturing. It was another year of education in Newton’s school of hard knocks. Always a quick study and as a result of these problems, the company eventually added steam power as a backup for deficiencies in river water.

1875 was a better year for the company. News accounts for that time indicate that the Newton brand was “well known from New York to California.” Looking past the raw material shortages they had encountered some 20 years earlier, they now stocked between 3 and 4 years worth of seasoned lumber. They had overcome the most challenging of obstacles and were now a competitive force to be reckoned with. Strengthening the business continued throughout the 1870’s, but the company wouldn’t exit the decade without one more significant blow. In 1879, Levi Newton, the family patriarch and company founder passed away, taking with him more than 40 years of horse-drawn vehicle manufacturing knowledge. Newton had prepared for this day by making his oldest son, D.C. a partner even before they moved to Batavia. Being extremely familiar with the day-to-day operation of the business, Don Carlos, succeeded him as president. Under the direction of Captain D.C. Newton – a military rank he had earned in the 52nd Regiment Illinois Infantry during the Civil War – the company continued to grow and by the early 1890’s, they were completing between 4 and 5,000 wagons per year.

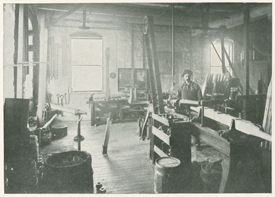

No matter the fortitude and desires of man, working long hours each day, six days a week will eventually wear on even the most valiant. In 1893, at 61 years of age, Capt. Newton succumbed to complications of diabetes, just weeks before his 40th wedding anniversary. At that time, H.K. Wolcott, Levi Newton’s son-in-law, took over as president. His knowledge of the business was also extensive since his tenure at the company dated back a quarter century to 1868. Wolcott continued the high standards associated with the Newton brand by replacing much of the time-consuming handwork in the factory with hydraulics and additional power machinery. These changes allowed the company to be even more efficient and price competitive while reinforcing the quality and overall value of the brand.

At the turn of the century and shortly thereafter, a strategic marketing phenomenon was taking place in the U.S. agricultural business world. The largest implement companies were jockeying for increased market share and many of them lacked the centerpiece of all farm equipment – the wagon. As a result, firms like International Harvester, John Deere, Moline Plow Company, Rock Island, Emerson-Brantingham (E-B) and others began looking for wagon companies to buy while also developing their own farm vehicle brands. By 1912, the popularity and success of the Newton Wagon Company had attracted the attention of Emerson-Brantingham in Rockford, Illinois. E-B purchased the company in the fall of that same year. With the acquisition, Emerson-Brantingham introduced Newton to an even stronger national dealer network enabling the brand to grow its presence with farmers, ranchers, and businesses. Over time, the more elaborate paint designs on the box were simplified while the extra coats of paint each wagon received were widely touted. Highly identifiable by the dropped front hound of later models, Newton offered more than 100 different styles built for various uses and sections of the country. Hauling capacities ranged from 1,500 to 10,000 pounds and options included a variety of brake configurations and seat styles as well as a footboard, folding endgate and different tongue styles.

E-B continued to build Newton wagons until the difficulties of the Great Depression began to hit the company hard. So hard that, in February 1931, the wagon division was separated as an individual entity and given the name, Batavia Body Company. The upshot amounted to a very quick end to Newton’s horse drawn wagon history. In fact, other than building a few horse-drawn business wagons during World War 2, the transition was so significant and complete that by the very early 1940’s, period directories indicate there was no longer any source available to even service Newton wagons with original parts.

By some accounts, Newton is credited with building as many as 7 – 8,000 wagons a year while employing a top number of around 150 men. Today, Newton wagons with original paint and accessories have significantly increased in value. While a turn-of-the-century double box farm wagon could have been bought for around $100, the increasing popularity of these vehicles has driven prices of some of the best preserved examples well into the four and even five digit range.

With a story harkening back to the days well before the California gold rush, the Newton wagon brand is forever tied to the American West. It’s a legacy that continues to grow, drawing the attention of collectors, museums, ranches and others looking for quality examples of a near-forgotten, but absolutely essential vehicle industry. Ultimately, Newton was a workhorse brand tempered by fire and tested by time. It was styled in the old-fashioned school of long hours, hard work, and handcrafted quality and from the first shaved spoke to the last riveted cleat, it was way of life destined to never sit silent in the shadows of history.

See more Newton wagons at www.hansenwheel.com