Twenty years ago, I wrote a story about a seldom seen part of our transportation past. I’ve never posted that article to the ‘Wheels’ site and thought it was high time I did. Hoping this is both helpful and informative...

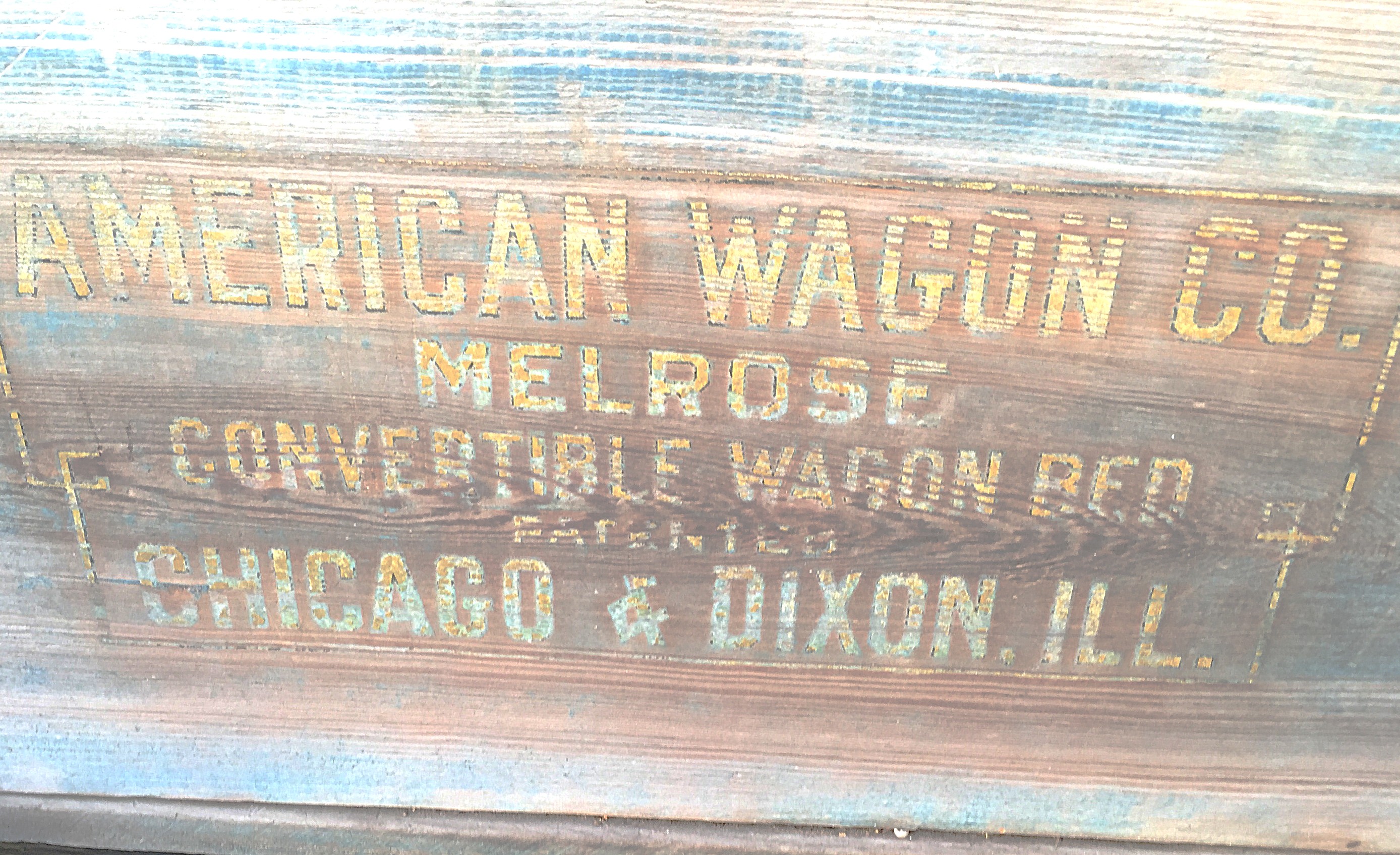

“Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door,” or so the saying goes. In the early 1900s, the American Wagon Company was one of several firms testing that philosophy by offering a new twist on an old design. Wagon boxes, the cargo-hauling portion of a horse-drawn wagon, were the company’s specialty. Believing necessity to really be the mother of invention, American was perfecting some of the most visibly significant changes to farm wagons in close to a half-century.

Between 1905 and 1909, the company secured at least two patents on their creations. Internal enthusiasm and faith in the product’s success was high. But, in just over a decade, the wheels of progress would take a hard turn.

Putting Ideas To Work

Based in Dixon, Ill., in 1911, American brought a promise of greater prosperity to the area. Sales offices were maintained in nearby Chicago, and catalog rhetoric indicated that more manufacturing sites were being contemplated to meet the growing demand. According to period accounts in the Dixon Evening Telegraph, the old Grand Detour wagon plant had been remodeled to meet the needs of the newly-arrived company. As the nation celebrated its 135th birthday, the factory officially began manufacturing in Dixon on July 5, 1911.

The company’s name implies that the firm was involved in full-scale wagon production. However, the box (often called the bed) was the only part of the wagon that the organization actually manufactured. But the American Wagon Co.’s box was far from ordinary and, in many ways, typical of the agricultural inventive genius prevalent during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Farmers, ranchers, and businesses of the day needed different wagon beds to haul different types of payloads. Most wagons met this requirement with designs that allowed the box to be lifted off the running gear and replaced with a different rack or bed as the need arose. For some, though, this type of traditional wagon design offered a less-than-adequate solution to hauling multiple varieties of cargo.

At issue were the added time and money involved in adjusting the wagon to meet every need. In order to help its customers avoid the difficult and costly exercise of buying or building different beds and frequently changing them, the American Wagon Co. marketed just one box that satisfied more than a dozen common uses. So, whether the farmer needed a hayrack to bring in loose hay from the field, a stock rack for hauling livestock, a corn wagon with built-in bang boards, a flax-tight grain wagon, an enclosed box for transporting poultry, or even a custom rig with ladder-back seats to carry a couple dozen folks to a Sunday afternoon church picnic, these quick-changing boxes catered to almost every need a rural farmer and businessman might encounter.

Going the Extra Mile

Early print advertisements and catalogs went to extraordinary detail explaining the value and benefits of American’s Melrose convertible wagon bed. The advertisements warned against confusing the company’s Melrose brand with cheaper, heavier, and cruder imitations. Some of the designs that American competed against could be found in the pages of Montgomery Ward’s discount catalogs, as well as among a few other makers and independent dealers. American’s morphing design was touted as a time and money saver. They also boasted greater durability, capacity, flexibility, and efficiency … all for about the same cost as a “first-class, single-purpose bed.”

Though the concept had been on the market for several years, a 1912 full-page advertisement describes the wagon bed as a “new farm invention.” Specific advantages included a “15-wagon-beds-in-one” design … a no tools, easy changeover configuration … strong, warp-free construction … and a 5-year guarantee. This was an unusually strong guarantee: Most horse-drawn wagon warranties of the day were limited to one year of coverage. Additionally, the box came with a free, 30-day trial. The American Wagon Co. even paid the freight. These were marketing tactics well ahead of their day.

Boxes were offered in 38- and 42-inch widths, and lengths of 9, 12, 14 and 16 feet. The boxes were said to hold as much as 100 bushels of shelled corn, 4,800 pounds of hay or two full-size cows/bulls. A 12-foot Melrose bed from the American Wagon Co. cost $30, according to the company’s 1911 catalog. While the 12-foot bed weighed 75 pounds more than the average wagon box, it was also 18 inches longer.

American was proud of the fact that no nails were used anywhere in the bed. Instead of wood supports, the company used steel sills to strengthen the bottom of the bed. Telescoping side braces were integrated with the hinged metalwork to fold the length of the box into its multitude of shapes. End rods were double-galvanized for extra protection against rust, and all metal parts were made from cold rolled steel. Sales catalogs proclaimed the wood to be long leaf pine, free from knots and double kiln-dried. With “superior quality” and “real functional value” as company watchwords, American worked hard to gain consumer confidence and make the buying process as simple as possible. Compared to the planned obsolescence of many products today, “In building this bed our whole aim is permanency,” company officials noted.

Seasons Change

By 1918, times were changing. The company had begun producing cabs, beds and other wooden parts for motorized vehicles. Like many others in the wagon-making trade, American was forced to branch into additional lines of business once the automotive industry gained a foothold. Following virtually the same production plan, but now with truck bodies, the company built at least four variations of truck beds. The convertible motor-truck bodies included 2-in-1, 3-in-1, 4-in-1 and 8-in-1 designs. Applications ranged from grain bodies to hog, stock, flat, poultry, basket and flared racks. A fine example of an American motor truck bed is found in a private vehicle collection in Bolivar, Mo. The Mark Besser collection includes a 1918 All-American brand farm truck with an authentic 8-in-1 American folding bed. It’s not only a good-looking fit to the truck, but obviously offered its original owner various hauling options.

Whatever the reasons – whether it was consumer reluctance to accept change, a limited distribution system, weak financial capital, or simply a casualty of transitional times – there is no evidence to suggest that convertible wagon beds ever grabbed a strong hold on either the automotive or farm wagon market. Even with an ingenious design and strong marketing principles, the wagon company disappeared from city directories after 1922. Ironically, the firm noted for such a highly adaptable product couldn’t quite adapt itself to rapidly changing times.

Today, at estate auctions, farm sales and roadside antique stores, vintage horse-drawn wagons can still be found. Local clubs, historical societies, museums, chuck wagon groups, antique dealers, yard decorators and collectors have strengthened a niche for these relics from the past. Some look for high or low wheels, others want wide or narrow boxes, stiff tongues, drop tongues, or even specific wagon brands. In the midst of it all are those looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack … the rare piece that adds depth to a quality collection while helping preserve a valued portion of America’s farming legacy. With only a decade or so of production, the Melrose convertible box is one of those hard-to-find pieces. By the company’s own admission, the boxes were built to last. So, while the whereabouts of most of these pieces isn’t known, somewhere another American Melrose box is undoubtedly waiting to be discovered and its creative dreams passed on to future generations.

– David Sneed is a historian of America’s early western transportation industry. He can be reached at: Wheels That Won The West® Archives, P.O. Box 1081, Flippin, AR, 72634; e-mail: info@wheelsthatwonthewest.com

Convertible Wagon Box Not Unique to American

In spite of the many unique features and farming benefits generated by its convertible wagon box, American was not the only company to offer such an inventive design. A few – but not the only – other firms with similar products included:

A) The Mutschler Co., Goshen, Ind. This firm made the “Mills” brand 8-in-1 adjustable wagon bed. It was guaranteed for one year and included a 30-day trial.

B) Montgomery Ward, Chicago, Ill. This legendary mail-order house not only helped market the “Mills” brand adjustable box, but also sold several other combination designs. Lengths of 12, 14 and 16 feet were offered and capacities were said to be a full 20 percent greater than an ordinary wagon box. A 30-day free trial and one-year warranty were among the features included with these 8-in-1 designs.

C) The True Manufacturing Co., Eaton Rapids, Mich. This organization marketed the “True” brand folding wagon box. It was built in14- and 16-foot lengths with five different positions, and an 85-bushel, 2-ton capacity. Like the American Wagon Co.’s models, the True box also touted the benefits of a no-tools-required, easily interchangeable setup.

D) The Stoughton Wagon Co., Stoughton, Wis. By 1917, this well-known firm was also building an articulating box called the “Stoughton Combination Bed.”

E) Jas. L. Wilber Co., Farmington, Mich. As early as 1888, Wilber was marketing a combined hay and stock rack wagon bed.

F) There were additional firms creating similar 'folding' beds that we've noted over the years of research as well.